Resolving cold cases important to Clark County coroner

It started with a young, pretty girl.

She was found face down and nude in the middle of Arroyo Grande Boulevard in 1980. Her cause of death was multiple stab wounds in her back and blunt force trauma to her head.

She should have been easy to recognize. But no one identified her.

The Clark County coroner’s office took X-rays, fingerprints and dental samples but couldn’t find a match in any existing databases.

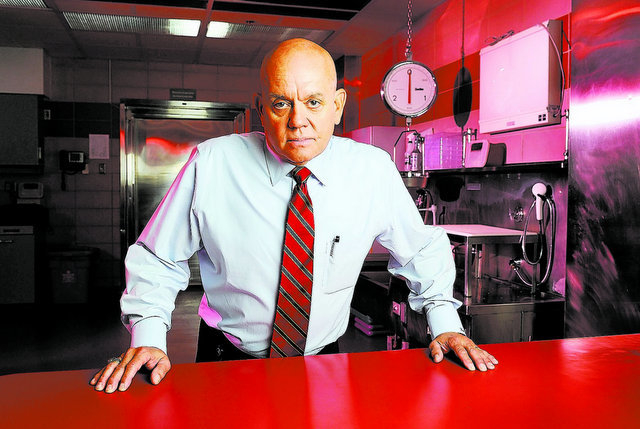

“Back in the day, that’s the way everybody did business,” Coroner Michael Murphy said. “We’re talking about the science of the ’80s and ’90s versus today. We were very limited in the resources we could get.”

In November 2003, the 14- to 20-year-old girl remained unidentified. The Clark County Coroner’s Office had exhausted all techniques available at the time.

Except one: the Internet.

“Some people came up with the idea of putting dead people’s photos on the World Wide Web,” Murphy said. “I said, ‘We’ve done everything else. Why not this?’ ”

The initial reaction was not positive.

“I was convinced I had made a big blunder, and I thought I would lose my job,” he said.

But then reports from family members started coming in, and people started identifying their loved ones.

“Within 24 hours, we had identified our first decedent,” Murphy said. “The response that we got was amazing. That started to kind of give us a boost. Within 72 hours, we had identified another one. A week later, another, and we were off the ground running.”

In the 10 years since the November 2003 inception of the online program, the coroner’s office cold case unit has identified 67 people. About 200 open cases remain.

“It’s not an exact science,” coroner’s office investigations supervisor Rick Jones said. “There’s a lot of hard work behind it.”

Murphy’s decision to put images of the unidentified people online, along with a coroner’s office in Fulton County, Ga., led to the founding of the National Missing and Unidentified Persons System, commonly known as NamUs, Murphy said.

NamUs compares family reports of missing persons with police reports of unidentified bodies.

“We got much more sophisticated about what we did,” Murphy said. “We put today’s science to yesterday’s cases.”

A federal grant in 2009 allowed the coroner’s office to exhume 54 bodies from the county cemetery for identification.

The exhumations began in 2010 and lasted 18 months while the coroner’s office retrieved DNA samples and other data, such as fingerprints if available, from the bodies.

The first exhumed body, a man, was identified in October.

But an unidentified woman exhumed during a different project looms over the office.

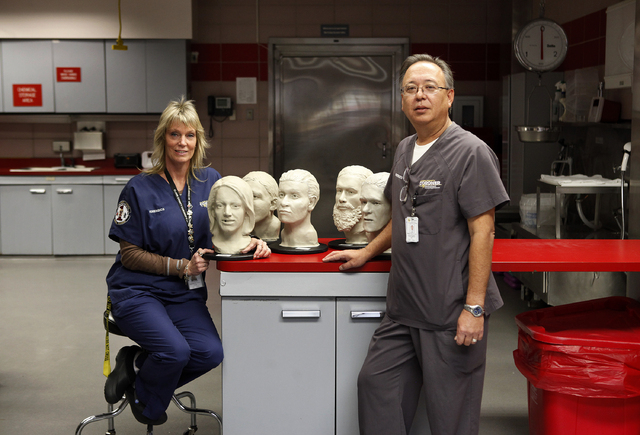

A 3-D printout of her head sits on a desk in the forensics office. She is missing a tooth. She watches the coroner and his staff work every day.

No one knows who she is.

Jane “Golfer’s” Doe died Jan. 4, 1995, and was exhumed in 2008.

The FBI printed the 3-D image as part of a facial estimation program.

“We sent the DNA through three labs; we tested almost every viable sample,” forensics supervisor Bill Gazza said. “So far, we’re going to work that case forever.

“We have always taken cold cases to heart. The issue is technology, funding and resources.”

Cold cases are only a portion of what the coroner’s office does on a regular basis. Workers perform about six autopsies or medical examinations a day, process paperwork, data and remains, investigate deaths around the valley and notify family members.

“We’re there to try to help people through the worst time of their lives,” Jones said. “That’s our foremost responsibility.”

Every deceased person who comes into the coroner’s office is given a standard medical examination and fingerprinted.

While the forensics department handles X-rays, dental and other data gathering, the investigations department attempts to identify the person and locate next of kin.

“We have a responsibility to find out what happened,” Jones said. “Sometimes you get a case that’s emotionally draining on you.”

After DNA is obtained, if no family members are found, the bodies are buried in the county cemetery. They are not usually cremated. The bodies could be held in the freezer at the coroner’s office for six to eight months before burial while forensics and investigative teams conducts their investigation.

“When we’ve exhausted all means, that’s when they are laid to rest,” Gazza said. “We work these cold cases forever. It’s important to us and their loved ones. We’re here to serve the community and serve those that can’t serve themselves — the deceased.”

The office identifies about six missing people a year from their missing persons caseload. Six to 12 investigations a year turn into cold cases.

“I wish we could do more,” Gazza said. “I’d love to get them all.”

As for the first unidentified girl entered into the cold case online program, the coroner’s office might finally have a lead.

The sister of an out-of-state runaway who went missing in 1971 thinks Jane “Arroyo Grande” Doe is her sister.

“She was the one that really sparked my interest in unidentified folks,” Jones said. “She’s somebody’s child out there, and that’s what we look at. Hopefully some day we can get this little girl identified.”

The staff at the coroner’s office will never stop looking into cold cases, and they will never stop trying to identify unidentified decedents, Gazza said.

“We’re the last responders to any investigation. We try to treat everyone with full respect, because no one else can defend them except for us.”

Contact reporter Rochel Leah Goldblatt at rgoldblatt@reviewjournal.com or 383-0381.

MISSING PERSONS ONLINE

More information about missing persons, unidentified bodies and the national database can be found at www.namus.gov.

Anyone can enter information about missing persons. After verification, each case will be searchable on the database.

Online coroners and medical examiners can enter information into the unidentified persons and unclaimed persons database.

Each individual case has contact information on it for people to call if they have any information about that case.