Tonight’s Oscars more than just a TV show for Las Vegas HIV survivor

Will “Dallas Buyers Club” win the best picture Oscar tonight for chronicling the life of Ron Woodroof, a macho rodeo cowboy who was blindsided by HIV?

Will the rail-thin Matthew McConaughey win an Oscar for best actor for his portrayal of Woodroof, a heterosexual who gave hope to thousands of AIDS patients by illegally importing unorthodox drugs as an alternative to AZT, the only drug on the market during the 1980s?

And will Jared Leto be named best supporting actor for his portrayal of the man-turned-woman Rayon, without whom Woodroof’s network of buyers never would have gotten off the ground?

Within a few hours, the envelopes will be opened as Ellen DeGeneres holds comedic sway onstage at the 86th Academy Awards. But it will be much more than a star-studded awards show for one Las Vegas man.

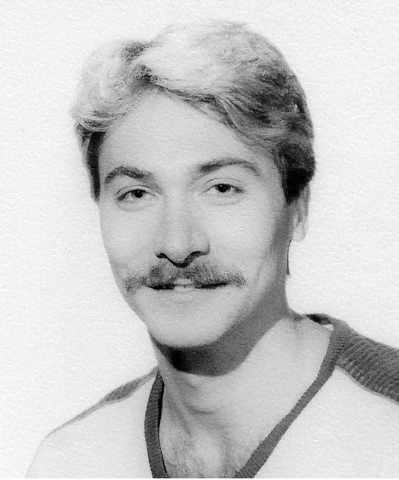

Dennis Dunn, 57, has defeated the greatest of odds. He has lived with HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, since 1982. Medical experts say the fact that he still is around is a virtual 1-in-10 shot, given his age and the ancient date of his diagnosis.

Woodroof was diagnosed with HIV in 1986 and died in 1992 despite the successes of alternative medications, which was the focus of the movie. By comparison, Dunn has survived for more than three decades, thanks to a medical breakthrough in the mid-1990s.

And not a day goes by that Dunn doesn’t feel incredibly fortunate, which is why he runs the Nevada AIDS Project and its 24-hour AIDS hotline in the Las Vegas Valley.

There’s also a bit of survivor’s guilt, which manifested itself after he saw “Dallas Buyers Club.”

“It brought all the memories rushing back, and it really hit home,” said Dunn, a Pittsburgh native and disabled Air Force veteran said of the film. “It was so devastatingly sad, that era. I cried inside for hours after. Bottom line is I lost so many wonderful friends in the epidemic, and I cherished each one.”

Dunn moved from San Diego in 2005 to lend a helping hand to the AIDS community in Southern Nevada, where there are more than 3,500 people living with HIV and more than 2,800 AIDS cases.

Since 1992 more than 9,000 people have been diagnosed with the disease and more than 3,000 have died because of it in Southern Nevada.

Those numbers are small in comparison to the carnage that AIDS has wrought across the United States and the world.

DEATH’S DOOR

AIDS-related illness was the No. 1 killer of men, most of them between 25 and 45, in the United States for three straight years in the early 1990s, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Dunn has had his share of close calls with death through the years. But unlike Woodroof, Dunn got help in time.

He was there for the medical breakthrough when a host of antiretroviral medications hit the market in the mid-1990s. At the time, the mantra of the day was “Hit fast and hit hard,” which is what thousands of others have done, including Dunn.

At the time, it was called HAART, or Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy.

“It’s a miracle I’m still living,” said Dunn, who works as a part-time usher at a casino when he is not out in the community and trying to raise money and awareness for his nonprofit. “There was a time when I thought I was on borrowed time, and I guess I still am when you think about it. But I can honestly say that I sometimes forget I even have HIV until it comes time to take my meds at night.”

He said the medication is not without its side effects. It gives him a “constant hum,” which he likens to a television being turned on all day. There’s dry mouth, nausea, loss of appetite, the usual side effects to which he has long grown accustomed.

But it’s either that or die.

It’s the same sort of cocktail that has kept thousands of other HIV-infected people alive as well, including such notables as basketball great Earvin “Magic” Johnson and Olympic gold medal winner Greg Louganis.

Known as protease inhibitors, the cocktail has all but eliminated what once was thought to be an automatic death sentence. It has turned HIV and AIDS into a manageable disease in the early 21st century. And yet to date there is no known cure. A vaccine, though promised as far back as the early days of President Ronald Reagan, has yet to be made.

Dunn isn’t alone. By 2017, roughly 50 percent of the total AIDS cases are expected to be mostly men over the age of 50, according to the CDC.

And yet there is no question that survivors such as Dunn are rare, a 1-in-10 shot, according to Dr. Renslow Sherer, a physician who specializes in AIDS research for the University of Chicago School of Medicine.

“He’s a long-term survivor,” said Sherer, who also was there at the beginning of the epidemic. “I see many of them. It’s not uncommon and yet you have to put it in perspective. At least 90 percent of their peers who had HIV in the 1980s and 1990s are gone. Think about that: 90 percent. They weren’t as lucky.”

Sherer said Dunn and others managed to stay alive because they kept infections at bay and had the money to pay for aggressive treatment in the mid-1990s. Because Dunn is a disabled veteran, the Veterans Administration helps foot the $7,000-a-month medical bill, for which he is grateful.

NO MEMORIAL WALL

Dunn has lived to witness the carnage in the past three decades. Fatalities grew so fast that the Memorial AIDS quilt itself had to be retired a decade after it was introduced in 1986 because there were simply too many deaths and not enough space to lay out all the quilts on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., where it was first rolled out.

To date, the disease has killed 636,048 people in the United States, according to the CDC. That is far more than deaths in the United States from World War I, World War II and the Vietnam War combined.

And yet there is no particular memorial for them, no day of remembrance, long-term AIDS survivors have lamented.

The early days of the disease were stressful. Dunn himself often wondered whether he was next as he read the sad news of the AIDS-related deaths of such public figures as Rock Hudson, Liberace, Arthur Ashe, Freddie Mercury, Ryan White and Robert Mapplethorpe over the years. They were among the many who put a face on the epidemic, an epidemic that Reagan once famously called the “gay cancer” and “nature’s revenge on gay people.”

Dunn has seen his own friends die as well. He is haunted by the memories of Radford W. Miller, Steven Handratty, Richard Weltzin, Kala Maddoc, Jerry Jones, Eddie Smith, all called before their time in Honolulu, where Dunn worked aboard a cruise ship for much of the 1980s.

It was jokingly referred to as the “Sin Cruise,” for all its good times and free loving.

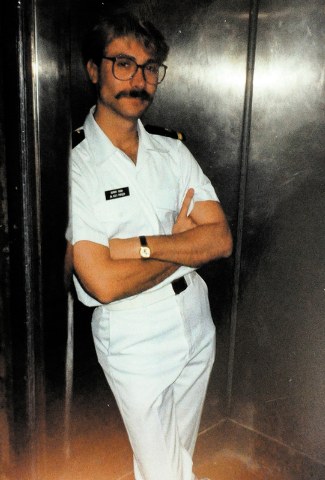

Dunn said he embraced the homosexual lifestyle while serving in the Air Force in the late 1970s when he was an administrative clerk stationed in Honolulu. He figures he contracted the virus sometime between 1978 and 1982, although he never really narrowed it down to any particular individual.

It was a time when condoms were unheard of, and the gay scene in Honolulu “was wild and free.”

“There were lots of sweaty men in tight pants prancing around with fans,” he said. “Lots of dance clubs. And although the military frowned on gays … my captain signed papers that allowed me to work after hours in one of the known gay establishments. Known to those at least who were in the know.”

GAY SCENE

Dunn, in retrospect now, says finding the gay scene was probably the biggest mistake of his life and ultimately led to his downfall. Although he had always exhibited gay tendencies much of his life growing up, he actually left his hometown of Pittsburgh and joined the Air Force after high school for different reasons: To escape a jealous girlfriend who had accused him of cheating on her — with a barmaid.

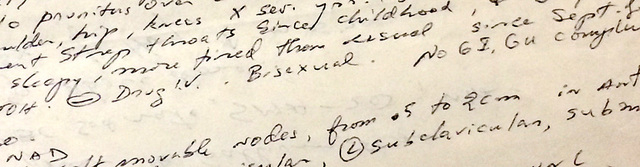

It wasn’t until 1982 that HIV came up. Dunn went in for a routine medical checkup at Tripler Army Medical Center. Doctors had a hard time figuring out why he had swollen lymph nodes throughout much of his body.

The physician described it as “persistent generalized adenoapthy.” He still has the medical document to prove it. He was only 26 at the time.

He wasn’t diagnosed with HIV until 1985, after the test first appeared on the market.

Dunn has been on some form of HIV medication since 1988. The alphabet soup of pills started with AZT, whose ineffectiveness was featured in “Dallas Buyers Club.” Dunn said AZT only made him anemic. After two years, he switched to another drug, DDI Didanosine, which only ended up causing fissures in his tongue.

Then in the early 1990s, he tried D4T/Stavudine and 3TC/Lamivudine. That gave him neuropathy, a tingling in the feet that he still has. He turns to medical pot to alleviate it. He bakes brownies.

Although Dunn appears healthy, he has had his share of close calls in his 30-year dance with HIV.

He had a cancerous lesion, known as Kaposi sarcoma, removed from his chest. He was hospitalized for pneumocystis carinii pneumonia, which is caused by a yeast-like fungus. It is common in AIDS patients and was the first symptom to appear in 1981 when five gay men inexplicably came down with it, two of them later dying, according to a Mortality and Morbidity Weekly Report by the CDC that year.

But perhaps the biggest brush with death came from a group of bacteria known as Mycobacterium Avium Complex, which led the lymph nodes in the upper chamber of Dunn’s heart to swell up. Surgeons caught it early and saved his life.

At the time, his weight dropped to 137 pounds, but at 5-foot-10, Dunn has never looked like someone wasting away from AIDS.

However, he has encountered discrimination when people find out he is living with HIV.

“There’s always a certain stigma you’re going to get from having it. I think younger people are more accepting. They’re more in tune with the times. Weren’t around when it was killing so many people. It’s the people who are in their 40s and 50s that go, ‘Ohhhh, get away,’ or at least if they’re not saying it, they’re thinking it. It just depends on how educated they are. I’m sure the average Joe on the street doesn’t understand it. They don’t think about it unless they have a family member who has it.”

There are plenty of occasions when he is calming somebody who has just been diagnosed with HIV and is calling the hotline, wondering what relocation to Las Vegas would be like.

“I tell them there is hope,” he said. “I guess I’m proof of that, for better or for worse. Probably for the better.”

Reporter Wesley Juhl contributed to this report. Contact reporter Tom Ragan at tragan@reviewjournal.com or 702-224-5512.