Water authority digs deep for third intake pipe at Lake Mead

Down at the bottom, the rain never stops.

It seeps from the rock walls and pours from the 600-foot shaft that frames a clear blue sky.

Pumps help to stem the tide, but still the water collects, turning this work zone 60 stories underground into a humid, muddy mess.

When it's finished in early 2013, the so-called "third straw" into Lake Mead will keep water flowing to Las Vegas despite drought and shortages on the Colorado River.

Right now, though, all this extra water is an unexpected complication for a project that is already complicated enough.

"It's not your friend in the tunnel business," said Project Manager Jim McDonald. "Water is always our worst enemy."

Intake No. 3, as it is officially known, is the Southern Nevada Water Authority's $700 million answer to a mounting dilemma: Roughly 90 percent of the valley's drinking water is drawn from Lake Mead through two existing intake pipes. So what happens if the lake shrinks low enough to shut down one of those pipes?

U.S. Bureau of Reclamation projections suggest Lake Mead will rebound somewhat over the next two years. But a few dry winters in the Rocky Mountains could easily erase all that, just as a decade of dry winters has erased 120 vertical feet of water from the massive storage reservoir.

Nowhere is the impact of the lake's fall more evident than on Saddle Island, home to the water authority's two existing intakes and now the staging area for construction of the third. The lake has receded so far, Saddle Island isn't an island anymore. It scarcely qualifies as a peninsula.

With that as her backdrop, water authority General Manager Pat Mulroy has described the third intake project as a race against time. The problem is there is nothing very speedy about construction on this scale.

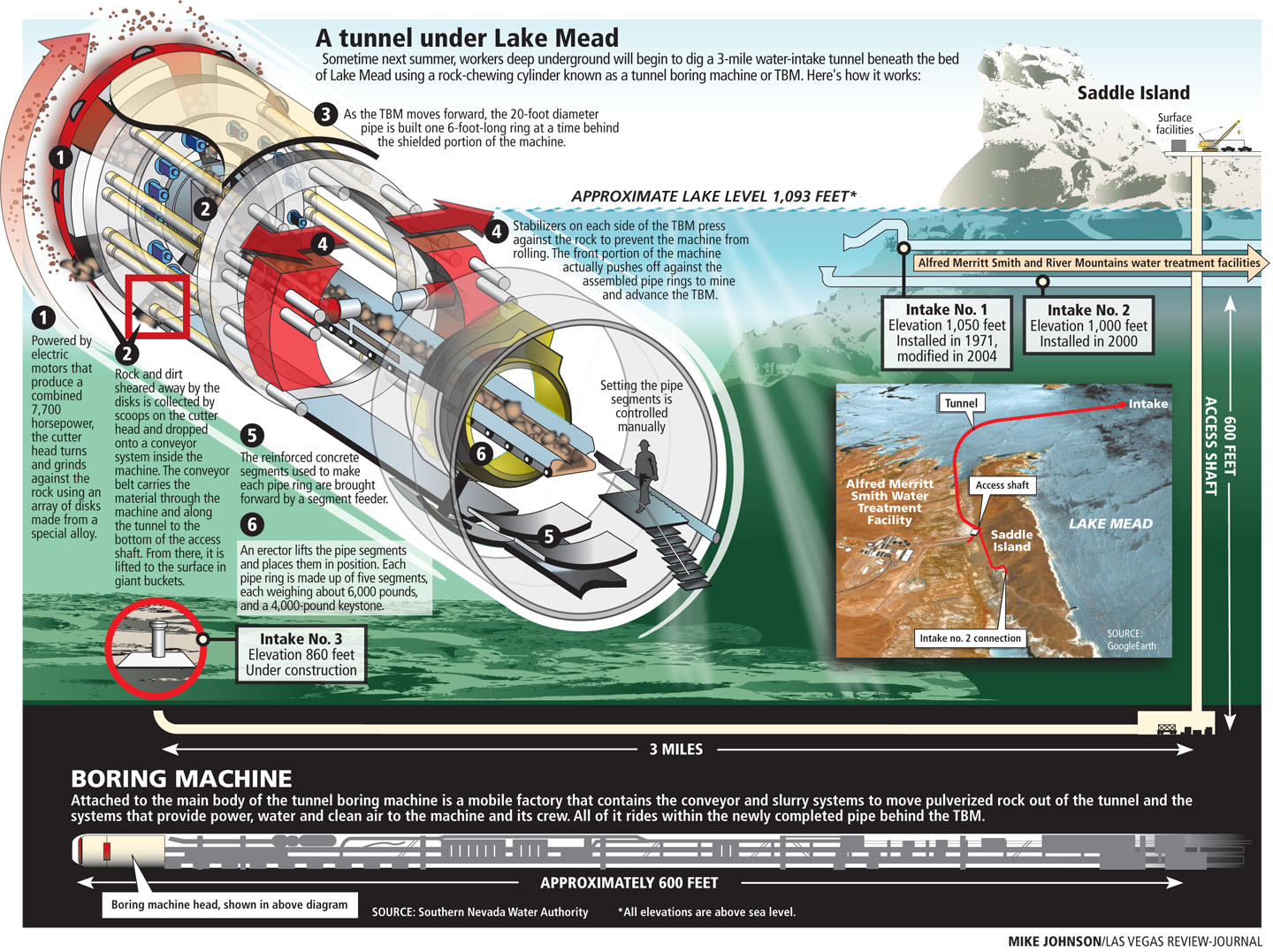

Imagine drilling a 23-foot-tall tunnel through 3 miles of solid rock. Now imagine doing it beneath the bed of the nation's largest man-made reservoir.

The finished, 20-foot diameter intake pipe will allow the authority to draw up to 1.2 billion gallons of water a day from Lake Mead even if the surface drops another 90 feet.

It also will give the authority access to the deepest part of the lake, where the coolest, cleanest water is found.

THE CONSTRUCTION CHALLENGE

To design and build the intake, the water authority turned to Vegas Tunnel Constructors, a joint venture of the Italy-based Impregilo group and its U.S. subsidiary, S.A. Healy Co.

Impregilo is one of the biggest contractors in the world, with projects that include flood control gates in Venice, Italy, new locks at the Panama Canal and the world's longest railway tunnel through the Alps of Italy and Switzerland.

The $450 million construction contract is the largest ever awarded by the water authority.

Vegas Tunnel won the job in March 2008. It has taken workers more than a year to get where they are right now, in the middle of a rainstorm at the bottom of the 600-foot access shaft.

The contractor expected to hit water, just not this much this soon.

Pumps running day and night send 300 gallons a minute out of the hole, but it just keeps coming through fissures in the metamorphic rock.

In one spot, it spurts from the ceiling like a garden hose. In another it bubbles from the floor like an artesian well.

Some of the groundwater, heated by unseen volcanic features, rains down at a balmy 90 degrees.

Dressed in raincoats and galoshes, workers are lowered into the downpour in a cylindrical cage to spend eight hours straight in the slop.

When it's time for lunch, the miners search for dry spots beneath scaffolding or under a tarp that keeps the controls on their drill rig from shorting out.

"Makes for a soggy sandwich," McDonald said.

Right now, the miners are working day and night to drill, blast and muck out a cavern 200 feet long, 45 feet wide and more than three stories tall. That's how much room they need to assemble the star of the show: a tunnel boring machine specially designed to chew its way under Lake Mead like a giant, rock-hungry worm.

THE BIG MACHINE

Fully assembled, the machine is the length of two football fields and weighs more than three Boeing 747 jetliners. The cutter head, a ridged platter 231/2 feet tall and studded with disks made from a special alloy, weighs 150 tons all by itself.

McDonald said excavation of the assembly area is on pace for completion in February. The machine will be lowered down the access shaft piece by massive piece and assembled over the course of about three months. McDonald expects it to start grinding rock in July.

The $25 million tunnel boring machine was designed and built in Germany specifically for the third intake project.

"It's the BMW of TBMs," McDonald joked.

The machine crossed the globe on a container ship. It took 61 tractor-trailers to deliver it in pieces from the Port of Long Beach, Calif., to the job site at Lake Mead.

Under ideal conditions, the machine will churn along in "open mode," carving its way through mostly solid bedrock and sending crushed rock back through the tunnel on a conveyor belt.

When the machine encounters unstable rock and heavy water infiltration, it will switch to "closed mode," a slower process that uses grout to pressurize the area around the cutter head and then pipes away the rock in a slurry.

It should advance about 30 feet a day, though McDonald said that's only an average. "We could have some 100-foot days, we hope, and we could have zero-foot days."

Core samples suggest the worst rock will come at the very beginning and the very end of the drilling operation.

McDonald said the tunnel boring machine might have to creep along in closed mode for the last half-mile of its journey.

The entire 3-mile trip is expected to take 23 months.

Along the way, the machine will negotiate at least one gradual curve, plotted to keep it in areas where the rock is best for digging.

After it tunnels about 40 feet beneath the Las Vegas Wash's old channel, the machine will begin to climb at about a 3 percent grade.

Tunnel boring machines such as this one work best when going uphill, McDonald said. "If you hit water, it drains away from you for one thing."

The machine was designed to operate at atmospheric pressures never before seen for a project of this kind. As a result, it comes equipped with a decompression chamber such as the ones used by deep-sea divers, though workers in the tunnel won't need to use it except in rare instances.

"We may not have to use it at all," said Marc Jensen, director of engineering for the water authority.

McDonald said the plan is to tunnel around the clock in three shifts at least five days a week.

It takes a crew of about a dozen workers to run the machine.

About 140 people are working at the site right now, not counting those involved in two smaller, related tunneling projects also under way.

The work force is expected to peak at about 200 next year, as construction ramps up on the pipe's intake structure, which will poke up from the bottom of Lake Mead at one of the deepest points in Boulder Basin.

BENEATH THE LAKE BOTTOM

Using submersible robots guided remotely from the surface, workers will plant explosives on the lake bed and blast a pit 50 to 60 feet deep.

After the rock is cleared from the pit using a giant vacuum, a concrete pad will be poured under more than 250 feet of water.

Then, sometime in mid-2011, the precast intake structure -- basically a reinforced concrete box topped with a stainless steel funnel, the whole thing 95 feet tall and 1,200 tons -- will be towed across more than 2 miles of open water and carefully sunk.

Once the intake structure has been secured to the pad, it will be cemented in place with more concrete.

Before any of that can be done, however, McDonald said the first chore will be to clear about 50,000 yards of silt that has settled on the lake bed over the past 70 years.

No deep-water divers will be used. The entire operation will be conducted by remote control from floating barges anchored above the work zone.

In addition to traditional lights and cameras, the men and their machines will use sonar and global-positioning technology to see in the pitch-black water at the bottom of the lake.

The finished intake structure should be in place by July 2011. At that point, the tunnel boring machine will still be almost a mile away.

For Jensen, the project's "gee-whiz moment" will come when the tunnel boring machine actually digs its way inside the submerged intake structure, a feat that requires the machine to hit within 6 inches of its target after 3 miles of digging.

"You've got to build it right to hit it," he said.

McDonald is also looking forward to "making that connection," though modern surveying and guidance equipment have removed a lot of the suspense.

"It's not unusual for it to hit within an inch," he said.

The wild card with this project is the challenge posed by "surveying accurately under 300 feet of water," McDonald said.

HOW LOW IT WILL GO

Conceptually at least, the finished intake will resemble the drain at the bottom of a bathtub, but it is not designed to suck the last drop from the shrinking reservoir.

Though the pipe's inlet will rest at 860 feet above sea level, it will only be able to draw water if the reservoir stays 1,000 feet above sea level or higher. That's because it will use the same pump station as intake No. 2, which stops working at elevation 1,000.

Jensen said original plans for the third intake included a pumping facility, but the authority delayed that part of the project to cut costs amid a sharp decline in revenue.

The roughly $200 million pumping facility and related pipelines still might be built at a later date, Jensen said. But if Lake Mead is ever allowed to drop significantly below elevation 1,000, the community -- and the region as a whole -- could find itself in the midst of a crisis no mere pumping station can solve.

"It's hardly more than a broad river at that point," Jensen said of the lake below the 1,000 mark. "You're right near the bottom."

For now, the surface of Lake Mead is holding at about 1,093 feet above sea level. The authority's Intake No.1 would be forced to shut down at elevation 1,050.

HOT AND RISKY WORK

McDonald said everyone is working as fast as they can, but safety is the top priority at the site. The conditions and the kind of work being done demand a cautious approach.

Flooding poses the biggest risk, but the job would be dicey even if it didn't cross directly beneath almost 4 trillion gallons of water.

"It's a mining operation. You're underground under a whole lot of rock," Jensen said. "This is a very risky project."

McDonald said working conditions should become more comfortable once the tunnel boring machine is up and running.

When that happens, those working inside the tunnel will no longer see the rock that surrounds them because the reinforced concrete pipe will be built around the tunnel boring machine as it digs.

"It's hot. Not unbearably hot, but hot," McDonald said of working inside the machine. "And there will be a little noise. You can hear it grinding rock."

Each time the machine advances, the pipe will grow by 6 feet as a new ring is added just behind the machine's shielded front section.

It will take roughly 2,500 rings, each weighing about 34,000 pounds, to line all 3 miles of tunnel.

The pipe could get crowded during construction. In addition to the conveyor belt and slurry pipe that will carry rock away from the boring machine, the tube will house a small railroad to shuttle workers and equipment to and from it.

It also will have miles of ducts and cable to supply power, water, light and fresh air to the machine and its crew.

In other words, workers can expect the inside of the pipe to be loud and dusty and sometimes cramped.

But here's good news, McDonald said: At least it won't be raining.

Contact reporter Henry Brean at hbrean @reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0350.

Down at the bottom, the rain never stops.

It seeps from the rock walls and pours from the 600-foot shaft that frames a clear blue sky.

Pumps help to stem the tide, but still the water collects, turning this work zone 60 stories underground into a humid, muddy mess.

When it's finished in early 2013, the so-called "third straw" into Lake Mead will keep water flowing to Las Vegas despite drought and shortages on the Colorado River.

Video and slide show of Lake Mead intake tunnel

BY THE NUMBERS

300

gallons of water a minute being pumped from the current work area, which is 600 feet underground and in the middle of a layer of saturated rock. The water is treated at the surface and released into Lake Mead.

833,000

gallons of water a minute the completed intake will be capable of drawing from the lake.

260,000

cubic yards of rock that will be excavated during construction of the tunnel. That's enough to bury a football field under a pile 40 feet tall.

1,500

Approximate weight in tons of the tunnel boring machine thatwill be used to excavate a 3-mile water intake tunnel beneath the bed of Lake Mead. The machine is about 600 feet long and 231/2 feet tall.

18

The number of months it took German manufacturer Herrenkneckt to design, build and deliver the tunnel boring machine that was special ordered for the project.

0

How many times the tunnel boring machine will be used after this. Though it will only have 3 miles on its odometer, the machine probably will be sold back to Herrenknecht and stripped for spare parts.