COMMENTARY: Green New Deal a peaen on to naive idealism

The highly publicized resolution known as the Green New Deal, inspired by the fevered socialism of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, insists that it is “the duty of the federal government to create a Green New Deal.” The proposal will, in time, go down as one of the nuttiest public policy documents ever written in the history of the United States.

In the short run, however, this thin 13-page blueprint has commanded extensive support in both the House and Senate and has received respectful commentary from progressive pundits who fail to grasp the fundamental resource constraints that apply to public and private spending alike.

Defenders of the GND think that by waving a wand over our intricate and interdependent social arrangements, they can remake society in their own image. The Green New Deal is oblivious to its many contradictory demands: cheap and quick construction of infrastructure in a crisis mode, but only by using costly union labor, engaging in endless environmental review and showing extensive deference to the preferences of indigenous peoples. It is impossible to critique separately each element in a stream-of-consciousness manifesto. So here I shall look at only issue: how to finance this monster.

Every new public program requires a budget that indicates how government will raise and allocate the needed funds. Ordinarily, for that process to work, government actors must recognize that at some point there are always diminishing marginal returns to public as well as private expenditures. Thus if it takes X dollars to reduce pollution tenfold from 100 units to 10 units, chances are that it will cost about X in order to reduce pollution tenfold from 10 units to 1. Does it really make sense to run that second lap, with a gain of nine, even if the first one, with a gain of 90, is successful? The social objective of any expenditure, public or private, is to stop at the point where marginal social gains equal marginal social costs. Additional expenditures at that point cost more than they are worth and should be opposed by all, regardless of their political persuasion.

This basic attitude applies even to sexy infrastructure improvements. It is commonly said that these expenditures are an investment in the future, and those touting the GND think, wrongly, that private investors and lenders will not make the requisite level of expenditures. In so doing they mischaracterize a benefit of private investment into a weakness.

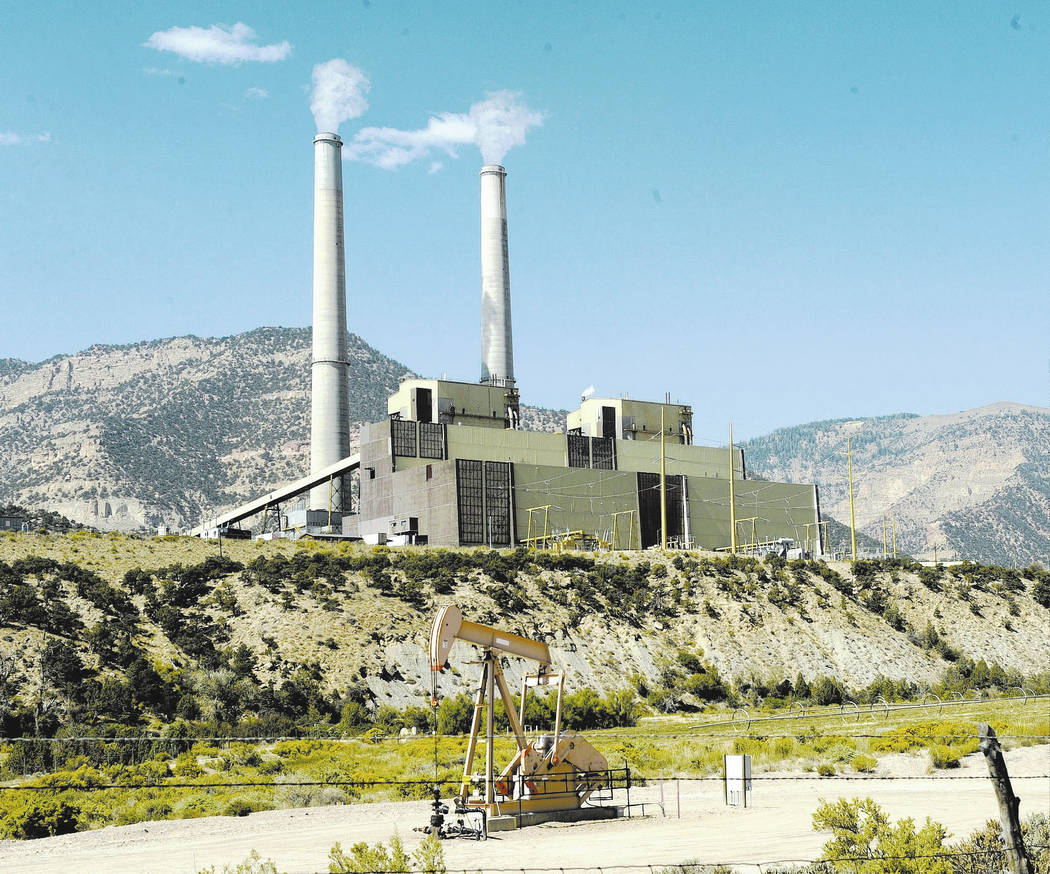

Speaking generally, some investments are good and others are bad. So, once again, making the right trade-offs at the margin is essential to sound planning. No matter anyone’s view of the severity of global warming, it is perverse to demand that 100 percent of our energy needs be secured by “clean, renewable and zero emissions” energy sources. The cost of that approach is prohibitive, yet defenders of the GND are oblivious to the enormous social waste of their naïve idealism.

The same absolutist mentality is evident in the GND demand that transportation systems be overhauled in order “to eliminate pollution and greenhouse gas emissions from the transportation sector as much as is technologically feasible.” To the uninitiated, the last phrase “technologically feasible” appears to limit infrastructure investments. But as conventionally understood, that condition asks only whether the technology exists to achieve a certain reduction, not whether it is cost-effective to do so. Thus in the simple example given above, if the technology exists, there is a duty to utilize available technology to move from 100 to one unit of pollution, if not lower.

The absurdity of this position becomes clear once the magnitude of the ambition is recognized. It is not just rusty bridges that have to be upgraded, but the entire multi-trillion-dollar transportation system, some of which is in relatively good condition and some not. Nor does the GND confront the nasty topic of infrastructure expansion to meet the needs of a growing population. GND enthusiasts should consider that California’s new governor, Gavin Newsom, announced he was abandoning outgoing-Gov. Jerry Brown’s infrastructure misadventure of building a high-speed train between Los Angeles and San Francisco. Too costly.

So just where then does Congress get the trillions of dollars to finance this infrastructure program? The defenders of the GND make clear their disdain for the unwillingness of the private sector to think about investments on the grand scale that they deem necessary. But one of the key functions of private investors is not to fund projects that cannot pay their way. Undaunted, the defenders of the GND will turn to the federal government to fund programs that the private sector will not. But why think that government agencies will know which projects to finance? After all, they could not succeed on projects such as Solyndra, whose modest mission was to create sustainable subsidies for solar energy. Why then assume that the gang that could not shoot straight could undertake still more ambitious programs when they have no knowledge of the multiplicity of new and uncertain technologies that will be featured?

Nor is it enough to decide which projects to fund. It is also necessary to decide how much money to invest and whether to participate in these projects as a equity investor or as a lender, both of which require extensive documentation and oversight.

Nor does the GND have any idea where the government will raise the funds for these improvident investments. It could just print more money only to risk massive inflation that will wreck the whole economy. Or it could raise taxes and squeeze out private-sector financing. Or it could float bonds to cover the costs, starving private firms of capital.

It takes immense sophistication to deal with funding sound projects. Yet the Green New Deal speaks only to benefits and ignores all costs. It does so because its proponents think the world may come to an end if we don’t do anything dramatic and soon. It is more accurate to say that the world may come to an end if this nation adopts a goofy progressive proposal that is bound to fail.

Richard A. Epstein is a professor at the New York University School of Law, a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution and a distinguished service professor of law emeritus and senior lecturer at the University of Chicago. His Review-Journal column appears monthly.