40 years ago, TV miniseries ‘Roots’ had nation talking about race

Yvette Williams was 19 when the landmark TV miniseries “Roots” aired over eight nights in January 1977.

She was no stranger to African-American history, and the stories of people whose ancestors — like those of author Alex Haley, who wrote the best-selling book upon which the miniseries was based — came to this country as slaves.

But Williams noticed something unusual as the episodes aired on the ABC television network: People approached her to talk about the events and themes depicted in the drama.

“That was really the first time when people would ask me questions — white friends and Hispanic friends and Asian friends,” says Williams, today chairwoman of the Clark County Black Caucus. “They would ask questions because they saw something on the show: ‘Did that really happen?’ For me, these were the very first conversations I had on a serious level that were around the issues of race and oppression.”

Consider the conversations it inspired, the history it shared and the pride it engendered in African-American viewers the legacy of “Roots,” which this week celebrates its 40th anniversary.

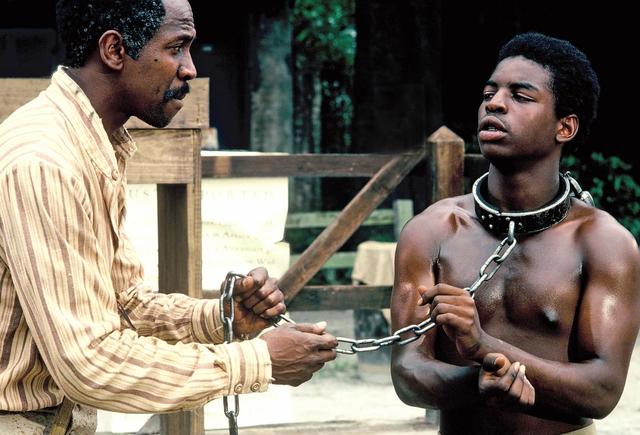

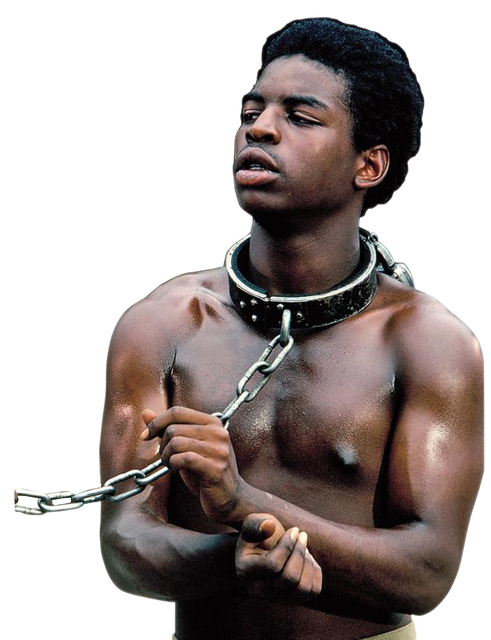

The TV drama was based on “Roots: The Saga of an American Family,” which became a best-seller upon its release the previous fall and in which Haley told the story of his own family. The lead character, Kunta Kinte, is taken from Africa and sold into slavery in the U.S. His experiences and those of the generations that follow make up the plot. The miniseries aired from Jan. 23 through Jan. 30 of 1977.

“Roots” was a massive ratings success. In a retrospective of the original miniseries, the cable network History — which last year unveiled an update of “Roots”— notes that the miniseries’ final episode was viewed by more than 100 million Americans, representing nearly 85 percent of television households at the time.

It also was a critical success and was nominated for 37 Primetime Emmy awards, winning nine, including Best Limited Series.

The drama was unusual at the time for its graphic, violent depiction of slavery and racial injustice. But it also created more personal ripple effects among those who watched it. “For me, it really started a conversation in the community across racial lines,” Williams says.

FIRST IMPRESSIONS

Claytee White, director of the Oral History Research Center at UNLV Libraries, saw “Roots” in Los Angeles after finishing college. “I think it was very painful,” she says. “I think it was in your face and it was difficult to deny, and I think a lot of people had denied that there was such a horrendous era in our history.

“I think people learned some lessons that a lot had not been exposed to before, especially a lot of people who (came from) outside of the South and those who did not have African-American history (classes).”

“It was very strong and emotional,” White says, but “I didn’t discuss it outside of my core group of friends.”

“At that point, I didn’t even know how to talk about it,” White explains. “At that point, I had only gone to school — until I was a junior in college — with African-Americans. It was not until I entered my junior year (at California State University, Los Angeles) that I actually participated in a class that was mixed. So I did not learn how to have a conversation with people outside of the black culture until later in life.”

The Rev. Dennis Hutson, pastor of Advent United Methodist Church, saw “Roots” while living in Chicago. He was working his first job after graduating from college and scheduled to begin ministerial studies later that year, in August.

Hutson already had read the book, and watched every episode of the miniseries because it was a landmark, he says. “I think almost every African-American in the country, if they had access to a television, watched it because it was historic for us.”

Hutson says he and some of his friends felt anger watching the drama’s no-flinches violence and portrayals of abuse. But, mostly, he remembers feeling “sadness, to just see how people were treated and devalued and dehumanized, and to see how families were broken up.”

Watching the drama also helped to “place some things into perspective for me,” Hutson adds.

He remembers himself as a rebellious teenager who would avoid his studies. In “Roots,” he saw how slaves were “not encouraged to learn how to read and write” and noted how young people sometimes tended to “not value the importance of reading and writing.”

“It just conjured up a lot of feelings within me,” Hutson says. “And, then it caused me to start to think about my situations and, as a product of urban, inner-city schools, how to overcome that and what to do to correct it or improve it.”

The Rev. Robert Stoeckig, pastor of St. Andrew Catholic Community in Boulder City, saw “Roots” with other students while attending college in Great Falls, Montana. He remembers how compelling the story was.

“It had gotten a lot of hype, so I think everybody was kind of interested in it,” Stoeckig says. “And after you saw the first episode, you were kind of hooked.”

PAINFUL RECOGNITION

“Roots” also “opened up some wounds,” Williams says, particularly in members of her parents’ and grandparents’ generations who were too close to having experienced or witnessed prejudice and racial injustice firsthand.

Williams says her mother-in-law would shy away from telling stories from her younger days. “She’d always say, “Just let those skeletons stay in the closet,’ ” Williams recalls.

Meanwhile, “Roots” offered viewers outside the African-American community a painfully vivid crash course in something they previously studied only in the antiseptic environment of a classroom.

“I had some friends, and I felt bad for them because they were feeling bad,” Williams remembers. “It was a sense of guilt, like ‘I can’t believe my ancestors did that to your ancestors.’ For the first time, the story was dramatized. You were invested in the characters. I cared about what happens to each of those characters.”

In her home today, Williams has a photograph commissioned by Haley and taken by a friend of hers, Foster Vincent Corder, that is a depiction of Kunta Kinte. She purchased it from Corder, and it has been in her family since 1982, she says.

“I fell in love with the picture … and I’m very excited to be able to pass it down to my children so they have an opportunity to enjoy it with their children.”

Michael Green, an associate professor of history at UNLV, was 11 years old when he saw “Roots.” He remembers the unusual-for-TV violence depicted in the drama.

“Maybe not like the (TV) violence you see today. Prime time TV in 1977 was pretty different,” Green says, noting he was too young then to have studied the nation’s history of slavery. But the series did effectively convey “a sense of how horrible slavery was.”

MULTIPLE INTERPRETATIONS

For just about every viewer, the multilayered, multigenerational nature of the drama helped to depict the horrors of slavery in an emotional, as well as intellectual, way.

Beverly Mathis had moved from Tennessee to Las Vegas in 1976 to begin a career in the Clark County School District that eventually would include serving as principal of Booker Elementary School for 16 years. She, too, had learned about slavery in school but found the dramatization of it in “Roots” to be unexpectedly powerful.

“It was very bizarre,” Mathis says. “It’s kind of like reading the Bible, knowing what it says, but every time you open it up, you learn something new.”

It’s possible to pick up new insights while watching “Roots” multiple times, she says.

Mathis remembers each episode becoming fodder for workday conversations the next day. Today, she says, “these types of movies just keep reminding us of what was and what we can do now.”

Hutson recalls, too, that the cast of “Roots” included almost every black actor or actress of the era. That also was a source of pride for African-American viewers, Williams says.

“We were really excited about being able to see ourselves on the screen and on TV, because, then, the few things we were able to see didn’t really give us that sense of self-pride. You had some shows, different ones, sitcoms, but they were never more than comedies.”

“The other thing that gave us black people a real sense of pride was when (the series was) nominated for almost 40 Emmys that year,” Williams says. “We really felt a sense of pride not only in the story being told but in the accomplishment of that.”

“Roots” helped to pave the way for four decades’ worth of TV and cinematic portrayals of slavery and other stories of African-American history. Does the miniseries that started it all hold relevance for younger viewers who have caught it only on DVD or in reruns?

Williams’ daughter, Alyse, 21, has seen the original miniseries and its sequel, and says that, for her generation, “I think it’s definitely a different experience now from when she saw it.”

“There were only so many TV stations. Now there are endless options,” Alyse says. “And there have been more movies about slavery and history, so we’ve been exposed to more. We’ve seen images of it.”

What was novel for her parents to see on TV may not be so for younger viewers. “I don’t want to say it’s less of an impact, but I think it’s a different impact,” Alyse says.

But, she adds, “it’s still, definitely, a very powerful series to watch. Then, to see the entire history of the family was definitely a powerful thing.”

Read more from John Przybys at reviewjournal.com. Contact him at jprzybys@reviewjournal.com and follow @JJPrzybys on Twitter.