Chronicle of gay Southern Nevada life records suffering, hope, acceptance

Back in the early 1970s, Dennis McBride was a young man on a mission. He knew he was gay, but he didn’t know why. In fact, the teenager didn’t know anything at all about his sexual orientation because residents in his Boulder City hometown still treated the subject as a scary taboo.

Those were the dark days of homosexuality in Nevada and the nation. McBride recalls expeditions to libraries around Las Vegas, searching desperately for a paper trail to his past and, just maybe, a road map for his future.

“There were no resources; nothing,” said the 61-year-old scholar, now head of the Nevada State Museum. “I couldn’t find anything about myself or my future, about what I was supposed to do.”

Even before McBride began the education that turned him into one of the state’s leading historical interpreters, he began chronicling his own gay life — and that of others here — as a way to keep a record of pain, suffering, loss and finally, hope and acceptance.

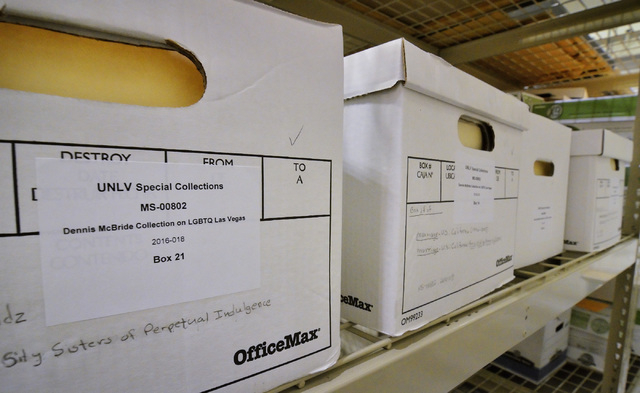

Over four decades, the slender man with a whispery-soft voice amassed thousands of photographs, journal entries, ticket stubs, flags and T-shirts, as well as hundreds of oral histories. In 1984, his research helped create the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender archive at the University of Nevada Las Vegas, a collection considered the largest and most inclusive of its kind in the mountain West.

It’s a personal and professional record of what it meant to be gay in Las Vegas. And get this: the strange and often-told tale of Wladziu Valentino Liberace barely scratches the surface.

In January, McBride donated another 25 boxes of files long kept in a Boulder City storage shed — a treasure trove organized and indexed by a professional archivist and historian.

“Dennis is one of those people I call an accidental historian,” said Gregory Hinton, who has researched the far-reaching effects of gays and lesbians in settling the American West. “I say that because people like him started very young, collecting and safeguarding all this history. It was generous of them to think of it and we owe them a great deal of gratitude.”

McBride said he sensed he was gay at an early age, before he even knew anything about sex or its orientations.

“In retrospect, oh yeah, I knew,” he said. “But in those days I was just weird.”

He came out in 1977, while visiting friends in Lake Tahoe. The couple looked at him and said, “Oh, we know.” He told a close aunt during a correspondence via cassette tape. She said she didn’t understand but loved him anyway.

Then came the hardest part: telling his parents.

Sitting in the dining room of the Boulder Dam Hotel, his mother said she didn’t believe it. His father, a truck driver and handyman who left the family about that time, was also a closeted gay. McBride believes he knew about his son all along.

The accidental historian then began reaching out to the wide, still-mysterious world of gayness Out West. In Las Vegas, there was a love-and-loathing relationship with both gays and lesbians.

BANNED IN NEVADA

Clark County and the state outlawed such behavior as cross-dressing and even same-sex dancing, but the casinos drew entertainers from around the world, many of them leading alternative and often outrageous lifestyles.

McBride began clipping small newspaper stories about what was then considered an aberrant life. In one bookstore, in the far back, he found a few books, pictures and articles on the subculture.

Often, his research surprised him. For instance, in 1862, the Nevada territorial legislature voted to criminalize some sex acts between consenting adults. The statute remained on the books until it was repealed in 1993.

Las Vegas had a long tradition of cross-dressing nightclub acts that were raided by police; beginning in the 1940s with a joint known as the Kit Kat Club in the city’s Five Points area.

The club was shut down — it became a Western bar — after servicemen from the Las Vegas Army Airfield — now Nellis Air Force Base — began frequenting the place. But there were other gay hangouts where cross-dressers took the stage, including the Swanky Club, the Green Shack and, decades later, Le Cafe, run by the colorful Marge Jacques, whose papers also are housed in the UNLV collection.

Other cross-dressers hit town for brief appearances. When Christine Jorgensen visited Las Vegas after gaining fame as the first person widely known in the United States for having gender-reassignment surgery, she was warned by police she’d be arrested. (She wasn’t.)

In the late 1970s, McBride began working with Nevadans for Human Rights, the first gay political organization in Southern Nevada. Later, working in a gay gift shop called R&R Assordid Sundries, he organized the group’s activist archives, which he donated to UNLV in 1984.

By then, the nation was confronting a mysterious AIDS epidemic. Victims of the disease were shunned in the community — denied health care and often even proper burials.

That’s when Liberace, the flashy entertainer who long denied he was gay, missed an opportunity to use his fame to help rally a response to the mistreatment of sick and dying gay men, McBride said.

“Of course, Liberace was gay,” he said. “It’s just absurd to think otherwise.”

In the 1950s, the singer sued a London newspaper for suggesting he was a homosexual. McBride’s collection includes a photo of the entertainer entering a British courtroom with his fans in tow.

“He couldn’t have come out in those days,” McBride said. “His fans would have turned on him. Still, his colorful style exploited that part of his nature. He was hiding in plain sight.”

Once, McBride recalls running into Liberace at a Las Vegas grocery store, the star surrounded by an entourage of young men.

“He was examining a little potted plant with great interest,” McBride said, “dressed like any housewife going out shopping.”

The historian remains baffled that in the 1980s, as gay men continued to die, the singer did nothing.

“We were fighting for our lives. We were dying,” McBride said. “Liz Taylor came forward for our cause, but we needed someone like him to help in the fight.”

Liberace died on Feb. 4, 1987, of AIDS-related causes. He was 67.

WITNESS TO A MOVEMENT

Along with lost opportunities came progress. McBride documented it all.

Today, more students are discovering UNLV’s gay and lesbian archives, which include the papers and memoirs of such gay activists as Eddie Anderson, Daniel Hinkley and Lee Plotkin.

“It’s one thing to collect this stuff, but it’s far more fulfilling to see students use it for papers or presentations,” curator Su Kim Chung said. “Some have said, ‘I didn’t even know this was here.’ ”

Now a new generation has the gay road map that McBride never had.

“These kids can see there are other people like them, that they have this collective history,” Chung said.

Soon, McBride plans to donate his personal journals and the 1962 book “The Homosexual Revolution” by R.E.L. Masters, which predicted events a half-century later.

In his office at the Nevada State Museum at the Springs Preserve, McBride read from the book’s front jacket, which laid out the gay objectives at the time of the Kennedy Administration — including same-sex marriage and an end to discrimination in the Armed Forces and in the workplace.

And there’s something else: McBride’s still-unpublished book.

Recently one house refused to publish “Out of the Neon Closet: Queer Community in the Silver State” because the author refused to cut anecdotes of several prominent state politicians whose lives came to a bad end because of their homosexuality.

So, who are they?

“For that,” McBride says with a smile, “You’ll have to wait for the book.”