Hospital volunteers help others conquer their challenges

Ever so slowly, 58-year-old Lori Wright, who’s on Social Security disability, makes her way down the hallway of Valley Hospital Medical Center. She limps, shuffles, wobbles and drags her left foot.

The wheelchair she pushes, held in front of her with her good right hand, is used to keep her balance and to hold packets of information she’ll deliver to other stroke patients. Wright, a hospital volunteer, sits in the chair only when her husband must move her in a hurry.

After 14 years of being shoved into and out of cars and vans by either Wright’s husband, paratransit drivers or friends, the wheelchair is battered. Much of its upholstery is ripped, as though crazed beavers have decided that the chair’s padded arms are better than cottonwood trees to gnaw on.

Wright, the mother of four grown children, was paralyzed on the left side from a stroke she suffered in 1999. She smiles and greets hospital employees who pass by as she heads from the lobby to the third floor. Two other days a week, Wright schedules a paratransit van so she can visit stroke patients at Desert Springs Hospital and St. Rose Dominican Hospital — Siena.

“It’s common for stroke victims who’ve been disabled, paralyzed or who can’t talk well, to initially wonder, ‘Why didn’t you just take me, God?’ ” she says as she heads for the elevator. “When I had my stroke, I was so scared. I volunteer because I want to help people realize what’s going on, help them realize they can still be valuable human beings. I tell them God left them here for a reason.

“After rehab, many go back to work. Others can be important for their children and grandchildren,” she adds. “I think it helps people going through a stroke to see that I’ve gone through it and can still be productive.”

Hospital administrators say volunteers are critically important.

“They give special care to patients, serve as a resource,” says Beth Bartel, who oversees Valley Hospital’s volunteer program. “They enhance the patient and visitor experience. Working alongside the staff, they perform the extra touches that often make a trying time less anxious.”

More than 220 volunteers, including teenagers and seniors, volunteer at Valley. You see them chatting with patients who don’t have family, running the gift shop, picking up extra pillows and blankets for patients, giving directions, preparing discharge information packets, bringing in pets for patients to cuddle, handing out books and magazines, counseling patients and families on what to expect from a procedure and during convalescence.

“Patients and their families thank us every day for what our volunteers are doing,” Bartel says.

As Wright stands at a nursing desk and pores over a list of stroke patients she’ll visit later on this day, another volunteer, Michael Sutherland, strolls down a fourth floor hallway in a blue shirt and tan Bermuda shorts.

If his grin were any broader, he’d probably dislocate his jaw. It’s a great day, a beautiful day for golf, he says as he stops walking to pantomime a swing. Only because you see the prosthesis decorated with a painting of the zany Animal character from the Muppets do you remember infection complications from diabetes caused his lower right leg to be amputated.

There is no trace of a limp as he walks — when you see him in long pants, it’s easy to forget he lost a leg just below the knee. He uses his experience of 12 years ago to help people negotiate the challenge of rehabilitating from injuries and procedures that can compromise mobility.

“It’s a terrible thing to deal with alone,” he says, smile gone, voice quavering. “Doctors have to be pretty straightforward. … I had an ulcer on my foot that wouldn’t heal appropriately and had several surgeries on it to try to save it. Then the decision had to be made … and you have to be strong. I had visions of myself with a peg leg like a pirate captain.”

Geoff Moore, who frequently accompanies Sutherland when he visits patients, says Sutherland gave him hope two years ago after he had his left leg amputated just below the knee because of complications from diabetes. He had a cut that wouldn’t heal and became infected. Moore became depressed when he learned he had to lose his leg if he wanted to live.

“Michael visited me when I was in rehab and really had the blues,” the 55-year-old Moore recalls. “He said, ‘You know, Geoff, your life is turned upside- down right now, but you’re going to be OK. ’ I asked him how he could know that and he pulled his pant leg up and he said, ‘This is how I know.’

“And then he told me how he was back playing the golf that he loved and I could be back doing the fly fishing that I loved. It gave me hope I needed,” Moore added. “Now I’m walking without a limp with my prosthesis and can stand in the river again to do my fly fishing. They’ve come so far now on artificial limbs because of research they’ve done on our soldiers who’ve gone to war.”

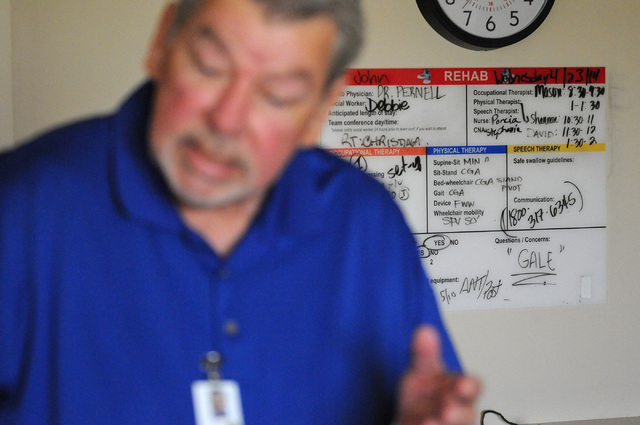

On this day Sutherland will visit 60-year-old Gale Rivers in the rehabilitation unit at the request of Jim Scussel, the department’s director.

“Michael has a way of connecting with patients on an emotional level that is just wonderful,” he says. “I made him star of the month in the unit for the way he works with people, the first time a volunteer ever won the award.”

Rivers is struggling to get around after a total left-hip replacement. Long-term use of corticosteroids for asthma interrupted blood supply, leading to avascular necrosis, the cellular death of bone components. That’s forced her to have two total hip replacements.

“You just have to follow what the doctors say and you’ll get around fine,” Sutherland says, pointing to his prosthesis as he walks around the room. “You can see I’m doing fine. Don’t give up.”

“I know, I know,” River replies, laughing. “It’s just going to take some time.”

Rehabilitation and the passage of time didn’t make Wright as whole again after her stroke as she would have liked.

“In my mind, I thought I’d go to therapy for a couple months and then I’d basically be OK,” she says. “But that didn’t happen. The brain is very complicated. I learned that the effects of a stroke can often be for life.”

Strokes, the fourth leading cause of death in the United States, occur when the blood supply to the brain is blocked or when a blood vessel in the brain ruptures, causing brain tissue to die.

Wright had gone to bed about 11:30 p.m. when she felt she needed to go to the bathroom. She leaned forward and was unable to stand, falling to the floor. She couldn’t use her left side, couldn’t talk.

She was just 44, a Californian who not only jogged regularly but who had been on two world championship Over the Line beach softball teams. Wright learned her stroke was caused by a previously undiagnosed genetic disease called Takayasu’s arteritis.

Though she got her speech and some mobility back during subsequent operations and rehabilitation, her neurological deficits forced her to leave retail work.

Today, Wright hobbles into the hospital room of 90-year-old Mary Parlette, who seems to be recovering miraculously from a stroke that initially left her unable to speak.

“Please read this so you don’t have another one,” Wright says, handing over a packet from the American Stroke Association. “You’ve been very lucky.”

“I know,” Parlette says, noting Wright’s disability. “I don’t want another one. I promise I’ll read it.”

One of Wright’s crucial strengths, say nursing assistant Gloria Rios and Tammi Ballner, a nurse manager who works with stroke victims at Valley, is her ability to impart hope to people while also being realistic.

“The patients and their families can see that she did not get 100 percent back but she’s still able to make a contribution and not sit home and feel sorry for herself,” Ballner says.

When her husband moved to Las Vegas in 2004 for construction work, she felt the need to be useful. She threw herself into volunteering for both the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association and hospitals.

Maura Mead of Maine is glad she did.

When Mead’s older brother suffered a stroke in Las Vegas in 2013 — he’s now near relatives in a nursing home in Florida — Wright helped her negotiate the challenges she faced as an out-of-towner.

“I made 20 calls from out of town, including the stroke support network, and she was one of three who called back and was the most helpful,” Mead says by phone from the East Coast. “She actually scheduled a paratransit bus and met me at the apartment where I was staying and told me who to call and what to do. I was so horrified and frazzled, afraid my brother was going to die and she got me through it. She’s a beautiful, selfless woman.”

Selfless is also how Kim Milosevich describes the 64-year-old Sutherland, a former Las Vegas Country Club cart barn operator who started volunteering after having to go on disability.

Milosevich’s 73-year-old father, Roger Burnett, had gone to Valley for a leg amputation in February and Sutherland soon visited him to offer encouragement.

“My dad looked so forward to those visits,” she says. “He became positive about the future because of them.”

But the health of her father, who suffered from severe circulation problems, worsened. He had a seizure.

“Mike came to the hospital and prayed over him,” Milosevich recalls. “And he met with every member of my family and talked to them.”

When Burnett died, Sutherland attended the funeral.

“He gave a very nice eulogy that meant so much to the family,” Milosevich says. “He didn’t have to do any of that but he really cared. What a wonderful man.”

Contact reporter Paul Harasim at pharasim@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-2908.