Transcatheter aortic valve replacement helps elderly patients

Milton Knauer, who spent much of his working life developing motors for garbage disposals, knew late last year that his own motor was wearing out fast.

Yes, he could tell that his heart, which had kept him running fairly smoothly for 85 years — he had gone in for triple bypass 37 years ago — was sputtering much more than it had in the past few years.

The symptoms of it misfiring were clear.

He was more tired than usual, unable to walk long distances anymore. When he did walk, he often suffered from shortness of breath, pressure in the chest and dizziness.

One day he got so light-headed that he passed out and fell to the bathroom floor.

A trip to the doctor and subsequent tests indicated Knauer’s aortic stenosis, which his cardiologist had been monitoring for four years, had become more severe. With a buildup of calcium or mineral deposits usually responsible for causing a thickening of tissue in the aortic valve — the aorta is the main artery carrying blood out of the heart — aortic stenosis restricts arterial blood flow from the heart to the rest of the body by not allowing the valve to open as it should.

Knauer’s aortic valve was so balky his symptoms worsened by the day. No medication could make it open properly.

“I’d just walk a little and have to sit down,” Knauer says from a recovery bed at Sunrise Hospital and Medical Center. “I knew something had to be done right away. I was lucky this new procedure was around. I feel better already.”

In January, Drs. Branavan Umakanthan and Nauman Jahangir led a Sunrise medical team that performed a 90-minute procedure known as a transcatheter aortic valve replacement. That procedure wasn’t being done in Las Vegas when Knauer’s valve trouble became apparent in 2010.

Then, a patient with aortic stenosis either had to be strong enough to live through four to six hours of open heart surgery — where the surgeon cuts through the chest bone, stops the heart, removes the valve and replaces it — or he would be left to become weaker and weaker, a cardiac cripple until death.

Each year in the United States surgeons perform about 99,000 of the traditional heart valve operations, with nearly all done to repair or replace the mitral or aortic valves, which are on the harder working left side of the heart.

“He couldn’t have survived open heart surgery,” Jahangir, a cardiac surgeon, says of Knauer, who spent three days in the hospital. “He’d already had bypass surgery and was just too frail. In the past there were no options for older patients.”

Without aortic valve replacement, studies show that around 50 percent of patients with severe aortic stenosis survive about two years and quality of life is greatly compromised.

TAVR has been likened to a balloon angioplasty, in which an interventional cardiologist such as Umakanthan uses X-ray visualization to direct a catheter — a long, flexible tube — through an artery, with a balloon device on the end of the tube inflating to help open up a narrowing in the heart.

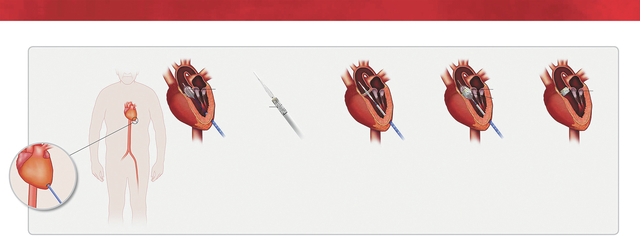

During TAVR, a catheter is inserted, with the help of imaging, through an artery in the groin (transfemoral approach) or, as Knauer had, through a small incision between the ribs (transapical approach). The tiny replacement valve is compressed and fed through the catheter until it reaches the aortic valve. A balloon expands the artificial valve within the patient’s diseased aortic valve, pushing aside the patient’s native valve with the prosthetic valve, and the catheter is removed. With the new valve replacing the old, blood flow is immediately increased throughout the body.

TAVRs have been done in Europe for more than a decade, and more than 50,000 of the procedures have been performed worldwide. The procedure was introduced at Sunrise a year after the Food and Drug Administration gave its seal of approval in 2011.

As baby boomers age, both Jahangir and Umakanthan say they expect TAVR to be performed more the future.

The manufacturer aimed the device at people 80 years old and up. Clinical trials in the United States show that implantation of the replacement device extended lives by two years.

Given that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports the average American has a healthy life expectancy of 79, some medical ethicists and economists have debated the wisdom of extending the lives of high-risk patients at the end of their expected life span with a costly procedure.

According to the American Heart Association journal Circulation, Medicare reimburses hospitals about $80,000 for each open heart surgery while cumulative one-year costs for TAVR can reach $100,000.

The argument against carrying out the procedure within the medical community has never gained much traction as doctors have said they should be advocates for individual patients, not accountants trying to bring down soaring health care costs.

“This procedure is something that can greatly enhance quality of life,” Umakanthan says.

TAVR requires a much larger operating theater, what’s known as a hybrid room, with the capabilities of both an operating room and catheterization lab with all its imaging equipment.

Although a heart-lung machine is not used in the procedure, one must be on hand in case of complications.

TAVR also requires a large collaborative team, including two interventional cardiologists, two cardiac surgeons and an anesthesiologist.

“We have to work closely together with the images,” says Umakanthan, who notes that cardiac surgeon Jahangir’s expertise was crucial in Knauer’s procedure, where the preferred and safer approach of going in through the groin area could not be done because Knauer’s groin artery was compromised.

Jahangir had to make an incision in Knauer’s chest and then he punctured through the heart’s left ventricle so the valve could then be positioned by Umakanthan into the right place.

“We always have to worry about too much bleeding,” Umakanthan says.

Because younger heart patients in need of a replacement valve have heard TAVR can be done without the open heart surgery that requires cracking open of the chest, Jahangir says many of them are asking if the procedure can be done on them.

He pointed out, however, that the gold standard traditional method has an operative risk that is much lower than what clinical studies have shown for TAVR.

In a November Journal of the American Medical Association report on nearly 8,000 TAVR procedures from 2011 to 2013, in-hospital mortality was 5.5 percent. Stroke occurred 2 percent of the time.

By comparison, studies show that for a 40-year-old who is otherwise healthy, the operative risk is less than 1 percent. Even if individuals have other health problems going into the procedure, the operative mortality rate is at 3 percent with the traditional procedure.

The traditional procedure also allows placement of a long lasting mechanical valve while TAVR allows only placement of a tissue valve that wears out in 10 years or less.

“Improvements may occur on the TAVR that allow it to be used one day on younger, healthier people,” Jahangir said, “but for right now it’s working well giving older people like Mr. Knauer an option at a longer life.”

Contact reporter Paul Harasim at pharasim@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-2908.