Shootings slowly changing police

The young father scarcely can contain his big smile.

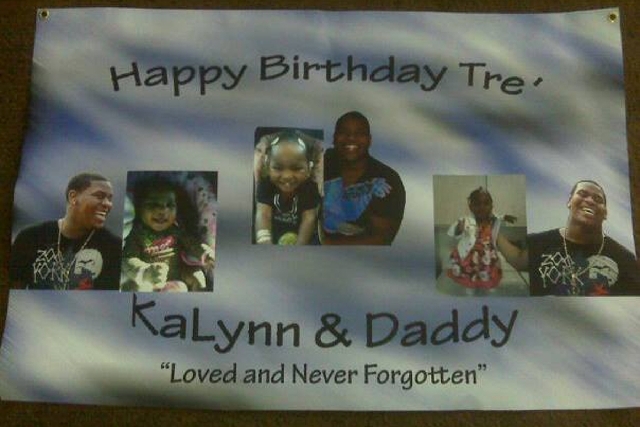

In one photo, the beaming man gazes at his giggling baby girl. In another, the man appears to place his hand on his daughter’s back, helping the toddler balance as she learns to stand. In the last shot, father and daughter sit side by side, posing for the camera. Her wide grin was clearly inherited from dad.

The pictures depict moments every new father would cherish. But the portraits aren’t real. They’re just images pasted together on a birthday banner for a dead man — of moments little KaLynn and Trevon Cole never shared.

Cole, 21, was killed five days before his daughter’s birth, during a botched Las Vegas police raid on his Las Vegas apartment on June 11, 2010.

KaLynn was there, too, in a way. Cole’s pregnant fiancée, Sequoia Pearce, was hiding in a nearby closet when Cole, unarmed and trying to flush a small bag of marijuana down a toilet, was shot in the head by Detective Bryan Yant.

His death was the first in a series of high-profile Las Vegas shootings in a span of a year and a half. Although it didn’t prompt immediate change, the shooting led to increased public scrutiny, a federal review and sweeping revisions to use of force policies at the Metropolitan Police Department and in Clark County.

Police now emphasize training officers to “de-escalate” those hostile situations that typically lead to deadly force. Sheriff Doug Gillespie has stressed the value of human life, and he has promised to hold officers accountable for mistakes.

Supporters have praised the department’s development; critics say the changes are likely superficial. Most are taking a wait-and-see approach.

Cole won’t see any changes his death inspired, but his daughter might. KaLynn turns 3 today.

WHITE AND WEALTHY; POOR AND BLACK

Cole’s death raised eyebrows, especially among local minority groups, but the general public kept mostly quiet until another controversial shooting a month later. Erik Scott, 38, was killed July 10, 2010, after brandishing a pistol in front of the Summerlin Costco on a busy Saturday afternoon.

Scott, a successful medical device salesman and graduate of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, brought controversy to the suburbs.

“There’s no part of the community that’s immune from this type of situation,” said Cal Potter, an attorney who frequently sues police.

Scott’s father led an aggressive campaign against the department, paying for billboards, holding vigils and generally casting doubt at the officers who shot his son.

It helped that Scott was white and his family was wealthy; Cole was poor and black.

As details about Scott’s shooting slowly filtered out, the public discovered that he had been heavily intoxicated on prescription drugs, armed with two handguns, and hostile to Costco security officers before police were called. After he refused police commands and reached for his holster, three officers shot him seven times.

Cole was a small-time drug dealer who sold less than 2 ounces of marijuana to undercover detectives in the weeks before the raid. He was unarmed when Yant burst into his one-bedroom apartment armed with an AR-15 rifle with a broken flashlight.

A veteran patrol officer recalled a lieutenant briefing officers about the inquests:

“He said, ‘We’re not worried about the Erik Scott inquest. It’s the Bryan Yant, Trevon Cole one we’re worried about,’ ” the officer recalled. “Every officer believes that Erik Scott’s shooting was 100 percent legitimate. But Bryan Yant (expletive) up.”

A coroner’s inquest for Cole was held in August 2010. Scott’s inquest was a month later. Both were ruled justified by inquest juries.

Cole’s jury believed Yant’s testimony that he saw Cole make “a furtive movement,” despite evidence that suggested an accidental discharge.

Both the Scott and Cole families sued. The department paid Cole’s family a $1.7 million settlement; Scott’s family eventually dropped their lawsuit.

POLICY CHANGES

Gillespie made a few policy changes following the Cole shooting, requiring SWAT officers to serve drug warrants instead of detectives. He also created the Critical Incident Review Team, which analyzes shootings to find trends.

Real reform was coming but the department wasn’t yet the main focus.

Clark County commissioners almost immediately considered changes to the coroner’s inquest process, long criticized for failing to hold officers accountable.

Cole’s inquest was the key. Many citizens — and officers — couldn’t conceive how the problematic shooting was justified. And they didn’t understand how Yant, although suspended for a week and then assigned to desk duty at the Fusion Center, kept his job.

“He’s admitted his mistakes, in the filling out of the paperwork,” Gillespie said during an editorial board meeting at the Review-Journal last year. “When it was brought to his attention, he admitted that he had made a mistake.”

A panel to revamp the inquest system, which included Gillespie and a representative from the local branch of the American Civil Liberties Union, was formed in October 2010, about a week after Scott’s inquest.

Their changes, approved in January 2011, included having an ombudsman to represent the dead person’s family and releasing evidence to the family before the inquest.

But the Las Vegas Police Protective Association, the union that represents rank-and-file officers, said their officers would not participate. Several officers sued to stop the inquest changes, claiming they were unconstitutional.

Around the same time, the PPA began advising officers in shootings to stop cooperating with their own department’s homicide detectives, who analyze the incidents for potential criminal charges.

Under the law, officers are only required to speak with internal investigators to determine whether they violated department policy.

After a nearly two-year legal battle, the inquest was scrapped in early 2013 and commissioners adopted a “fact-finding” review. The new process involves few witnesses, no jury and no testimony from officers involved in the shooting.

Allen Lichtenstein, general counsel for the Nevada ACLU, said the new process pales in comparison to the process the panel suggested.

“It’s been totally dismantled,” he said. “We worked long and hard on the process, that would not be perfect, but one that would release all sides of a story and increase transparency. Instead of allowing that to go forward, we scuttled that process.”

The result? A homicide detective answers questions about his investigation for a few hours.

“People can question those who wrote the reports, but it’s not the same thing as questioning the eyewitnesses,” Lichtenstein said.

An officer who has been in a shooting and through a coroner’s inquest said most officers want to tell their story. Some even enjoyed the inquest process, he said.

“Cops did that for 20 years. We sat down with homicide; we did the inquest. But when they brought in an ombudsman, we figured they’re only going to try to twist our words for their civil lawsuit,” said the officer, who asked for anonymity because he wasn’t authorized to speak. “Why give them any ammunition?”

‘DEADLY FORCE’ INVESTIGATION

It wasn’t until the Review-Journal published its “Deadly Force” investigation in November 2011 that scrutiny shifted from the coroner’s inquest to the police department.

The yearlong investigation covered two decades of shootings and found the department was slow to change and reluctant to hold officers accountable.

Ten days after publication of “Deadly Force,” officer Jesus Arevalo shot and killed Stanley Gibson, an unarmed, mentally ill Gulf War veteran.

Attorney Andrew Lagomarsino represented Cole’s family in their lawsuit against the department and currently represents Gibson’s family.

“Both shootings confirmed the obvious,” he said. “It took away Metro’s ability to deny they had a problem.”

The shooting, on the heels of the study, created a firestorm. Gillespie promised changes. His agency began working with the Department of Justice’s Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS) office on an eight-month study, which culminated in November 2012. It laid out 75 findings and recommendations for the agency, covering issues from a lack of “fair and impartial policing training” to reforming a “police-friendly” Use of Force Review Board.

Gillespie spent much of 2012 implementing his own changes before the COPS report was released. He announced a new use of force policy in July that states the department is “committed to protecting people, their property and rights” and that “the application of deadly force is a measure to be employed in the most extreme circumstances.”

The department spent five weeks retraining. Officers are also required to undergo new reality-based training, where they make decisions on use of force in real-world scenarios, three or four times per year.

The Use of Force Review Board also got a makeover. Previously considered a rubber stamp that favored the officers, the board of three civilians and four officers was modified to examine the events preceding a shooting, not just the moment an officer pulls the trigger.

The board’s revisions were on full display earlier this year when it recommended severe discipline in two shootings. Arevalo faces termination for separate incidents, and two supervisors in Gibson’s shooting face demotion or suspension. Officer Jacquar Roston, who in November shot another unarmed man in the leg, also faces termination.

Lichtenstein said the department’s discipline has been strengthened, but it’s unclear how well it is implementing its training. And he cautioned that Roston and Arevalo have not yet been fired.

“It’s one thing to have policies, but unless you have an actual evaluation of whether those policies are getting through in the training, how do you know if the people in the field are following them or doing what they’ve always done?” he said. “Metro and the feds haven’t done anything to devise methods for ascertaining that.”

SIX-MONTH REVIEW DUE SOON

But the first test may be on its way.

The COPS office will soon release a “very detailed” six-month report on how the department has implemented recommendations, said Sgt. Kelly McMahill. She works with the Police Department’s Office of Internal Oversight, created shortly after Gibson’s death.

Afterward, McMahill’s office will release its latest quarterly report reviewing police shootings.

“We felt it was better to have them (COPS) report objectively on our progress, rather than do it ourselves,” McMahill said.

And an in-depth statistical analysis report, which will look at police shooting data over the past five years, is currently being reviewed by Gillespie and executive staff, she said.

Capt. Tom Roberts said the department is about 80 percent done implementing the COPS suggestions, and the sheriff has been “adamant” that all guidelines become firm policy.

“We’re constantly revising our use of force policy to ensure we can stay ahead of trends and look at the best practices around the country. We want to be on the cutting edge of the best training and policies around,” Roberts said.

He said civilian Use of Force Review Board members will soon respond to police shootings, much as the district attorney’s office sends prosecutors.

“You don’t get as good of knowledge about what it’s all about until you’re out there feeling it, watching it,” Roberts said. “I believe it will help those civilian board members better understand the investigation if they go on the front end, and it should help increase transparency with the public.”

Lawyers for Gibson’s family aren’t convinced the department is more transparent.

Potter, who represents Gibson’s wife, Rondha Gibson, said he’s concerned the police union has taken such a negative stance against the sheriff, even though it signed off on the use of force changes.

“They don’t want to be held accountable for anything,” Potter said. “Instead, they accuse the sheriff and his administration of being political.”

Lagomarsino, who represents Gibson’s mother in a separate lawsuit, said the Use of Force Review Board’s internal report, which called for Arevalo’s firing, has not been made public.

“They took all their statements on this thing within a week of the shooting,” he said. “It makes people mad. It makes people think there’s something worse there than there might be. ... If they’re completely transparent about what happened, it would be better for the Gibson family and the community to heal. Instead, they’ve decided to drag this out.”

ONE FAMILY MOVED ON

Neither Gibson’s family nor Cole’s family will ever be healed. But the two families are in very different places.

Cole’s mother, Nichelle Bratton, and his fiancée, Pearce, moved to California with KaLynn a few years ago.

Bratton and Pearce have grown even closer since Cole’s death and live just around the corner from each other.

“She’s my daughter,” Bratton said. “She’s not going anywhere. We are stuck together for life.”

Because of their proximity, Bratton and Pearce are able to eat dinner together several nights a week, and Bratton gets plenty of time with her granddaughter.

KaLynn often reminds Bratton of her son — the way she talks, the way she smiles, her feet, her fingers. Bratton keeps a poster-size photo of Cole in her home, and KaLynn often talks to it.

“She says, ‘Hi, daddy. I’m being good. I promise,’ ” Bratton said. “I’m very grateful. Some mothers and fathers who have lost children unfortunately weren’t able to leave a grandchild behind for their parents to enjoy. I’m so appreciative that God blessed me to leave a piece of him.”

Bratton has no intention to live in Las Vegas, although she doesn’t blame the city for her son’s death. She was in Las Vegas in May, just a few weeks before the anniversary of Cole’s shooting, and went with a small group to the apartment where her son died.

She was there a few minutes when the renter appeared, startled at the group outside his door. Bratton explained that her son lived there before an accident took his life. The man asked if Bratton would like to come inside.

“He was so nice. ... I said, ‘No, sir, thank you,’ ” she said. “It was eerie going back. But I think if Trevon could speak to me, he’d tell me not to let it affect you.”

Rondha Gibson, who has remained in Las Vegas, hasn’t been as fortunate. Rather than becoming closer with her husband’s family, who hugged and cried with her the morning of his death, they have become estranged.

She didn’t appreciate her mother-in-law filing a $20 million lawsuit before she filed her own lawsuit, believing Celestine Gibson wanted to represent Stanley’s estate.

“Like I told them, I don’t give a damn about this money. Just respect your son. I’m not trying to be greedy,” Rondha Gibson said.

Lagomarsino said Celestine Gibson never wanted to cause animosity with her daughter-in-law.

“We support her, and we don’t know why she’s saying that,” he said.

Rondha Gibson said she doesn’t hate Arevalo. She told him as much when they met outside a courtroom several months ago.

But she hates what her husband’s death did to her.

“I’m just not me anymore. It’s not fair to my nieces, or my dog, when I feel scared walking him. It’s not fair to everyone,” she said.

After her lawsuit is settled — she doesn’t know when that will be — she hopes to open a bar in Las Vegas in her husband’s honor.

“I want a place where fellas can come and go, and just be fellas. A place a veteran can come to enjoy yourself. Male veterans got it worse. They’ve got nobody to turn to. They can’t cry.”

Contact reporter Mike Blasky at mblasky@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0283. Follow @blasky on Twitter.