New Nevada DNA swab law sees little pushback

A Nevada law that requires DNA samples be taken from every person arrested on a felony charge — and criticized by civil rights groups as an invasion of privacy — has seen surprisingly little pushback in the four months it has been in practice.

Before the law went into effect July 1, cheek swabs were used to collect DNA only from anyone convicted of a felony. But last year, the Legislature passed Senate Bill 243, often called “Brianna’s Law,” named after 19-year-old Reno woman Brianna Denison, who was raped and murdered in 2008. James Biela was later convicted and sentenced to die for the crimes.

Proponents of the law said it could have prevented the murder because Biela had a previous felony arrest.

The new law means arrestees have their DNA taken before they are even assigned a jail cell. The data is put into a national FBI database called CODIS, where it will remain indefinitely.

Nevada’s forensic labs have taken the massive project in stride, and only one person out of almost 5,000 samples taken has tried to refuse the swab.

‘BLOW TO GENETIC PRIVACY’

Before the new law, 300 to 500 DNA samples were sent each month from Southern Nevada jails to the Metropolitan Police Department’s forensic laboratory. Now more than 1,500 per month are collected.

Each week, the approximately 60,000 samples held in the Southern Nevada database are searched against samples collected in Northern Nevada’s data set. The state’s two labs are overseen by the Central Repository for Nevada Records of Criminal History in Carson City.

Then all of Nevada’s samples are searched against the FBI’s collection, which houses more than 12 million samples of DNA from arrestees, convicts and crime scenes.

Invasion of privacy is the root of the problem for most of the law’s critics.

But Metro’s CODIS administrator, Julie Marschner, said a person’s DNA sample is not attached to their name. It’s labeled by number, so when two profiles match during a database scan, there are extra steps required just to find the offender’s identity.

Once the name and sample are matched, Marschner said, the sample is rerun to make sure nothing glitched. Then a second sample is taken from the arrestee, and the process happens again to be sure it’s a match.

The sample is taken during the booking process at the jail. If the court doesn’t find initial probable cause in the charge, the law states, the sample is destroyed before it can leave the jail, bound for the lab. So it is never uploaded into CODIS. Since July, that has accounted for about 200 samples.

Samples also aren’t taken from juveniles unless a court certifies them to be charged as an adult. If a juvenile sample were to be taken and brought to the lab, it would be destroyed before being tested.

It can take about two months from the day a sample is taken to the day it’s uploaded into CODIS, Marschner said.

The American Civil Liberties Union took a strong stance against the new law, with staff attorney Michael Risher calling it a “serious blow to genetic privacy.”

ACLU spokeswoman Vanessa Spinazola is part of a legislative subcommittee that discusses the implementation process. The subcommittee considers changes and amendments that should be made to the law. She has two main worries: that DNA samples will be used to search against specific family members of offenders and that not enough DNA samples will be destroyed even if arrestees aren’t convicted.

LAW’S WORDING LEAVES QUESTIONS

Wording in Nevada’s law has left some confusion about when DNA samples should be destroyed.

A portion of the original Senate Bill 243 said that “the biological specimen be destroyed and the DNA profile and DNA record be purged from the forensic laboratory, the State DNA Database and CODIS on the grounds that: The conviction on which the authority for keeping the biological specimen or the DNA profile or DNA record has been reversed and the case dismissed …”

The section is talking about an expungement process, but many of the legislative subcommittee members misunderstood because it’s a lengthy section with dozens of subsections and thought it covered all DNA samples taken.

In actuality, once a sample from Nevada enters the CODIS database, it probably will never be deleted.

Even if the arrestee is cleared of charges, their DNA stays in the database. All two dozen states with similar laws have different policies on when — or whether — to throw out samples, but in Nevada, a person has to fill out an expungement form.

If approved, the physical sample is destroyed and the CODIS file is deleted.

But the ACLU thinks the form is too complicated. It requires official court documentation that, Spinazola said, some people won’t know how to attain.

“We don’t think people will go through with the expungement process,” Spinazola said.

Metro’s forensic lab, directed by Kimberly Murga, has collected more than 4,700 samples since July. Only five people have submitted the expungement form.

All five were turned down because the lab deemed them incomplete or incorrectly filled out.

The ACLU wants Nevada to look into an automated expungement process that some states have tried to use.

But Murga said too much manpower would be required for the lab to follow every court case and to pull the physical and digital sample for each to be destroyed. She doesn’t think the automated process is a possibility yet, either.

“There’s not a fail-safe way,” Murga said, “The IT infrastructure — it just doesn’t exist right now.”

Even fewer people who have been arrested have tried to refuse the swab to start with.

In fact, there has been just one.

Metro Capt. Richard Suey from Clark County Detention Center said that as of this week, only one man has fought having his sample taken. When that happens, the jail gets a telephonic search warrant and then takes the sample via blood draw. The jail has put its workers through new training that teaches them how to explain the swabbing process to arrestees and how to attain a search warrant if necessary.

Suey, Murga and Spinazola all expressed surprise that there haven’t been more refusals.

“I’m also surprised on how willing the criminals have been in helping us fight crime by voluntarily scrubbing their own mouths for DNA,” Suey said by email to the Review-Journal. “Never expected this much voluntary compliance.”

Suey said 85 percent of inmates booked into the center are not convicted.

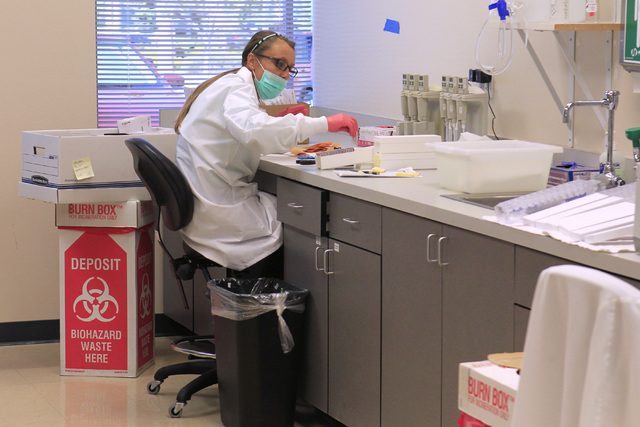

LAB TAKES GROWING WORKLOAD IN STRIDE

While the law itself is messy and will need clarification in the next legislative session, the forensic labs have kept pace with the massive workload. With more than 1,000 extra samples per month, the lab has had to adjust its operations to keep up.

Part of the bill that went into effect last year raises money for the new process. Starting July 1, 2013, a $3 fee was collected from every person convicted of a felony, misdemeanor or gross misdemeanor in the state. The funds went into an account that was to pay for equipment, extra swab kits and more staffing once the actual arrestee swab policy went into effect.

Since July 2013, more than $588,000 was raised, Murga said. The lab, which originally only required one technician to process DNA samples, has hired three additional full-time employees and one part-time worker to do the work. The hires happened in January so that there would be enough time to train before the second half of the law went into effect, but the funds available in January only covered one and a half positions. This means Metro’s general fund paid for the other positions initially, and as the $3 administrative fee gains more momentum, it will cover the employees’ salaries, Murga said.

Processing the spike in samples comes at a hefty price, too. To purchase, collect, process and upload one sample costs about $75. That means more than $100,000 per month in DNA felony arrestee samples.

Above all, Murga said, what’s important is that CODIS is able to match more samples now. She reported 31 CODIS “hits” since July 1 that match arrestee samples to crimes that range from burglary to sexual assault. And the results are far-reaching. Murga reported Nevada matches all the way in Delaware and Chicago.

Murga’s lab is keeping up, Suey’s jail has transitioned into the new law smoothly, and the ACLU is taking what it calls a “wait-and-see” approach. There’s no doubt, all three agreed, that clarification will be necessary in the next legislative session to Brianna’s Law.

Contact reporter Annalise Little at alittle@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0391. Find her on Twitter: @annalisemlittle.