Victim’s son agonizes over murderer’s death defiance

"Why is he alive after 30 years? He still is on death row. Time to go."

Jim Monahan has been pondering that question a lot in recent days.

March 27 marked the 30th anniversary of the day Las Vegas police arrived at his door and told him, his sister and mother that his father had been found shot to death in a van parked along Boulder Highway.

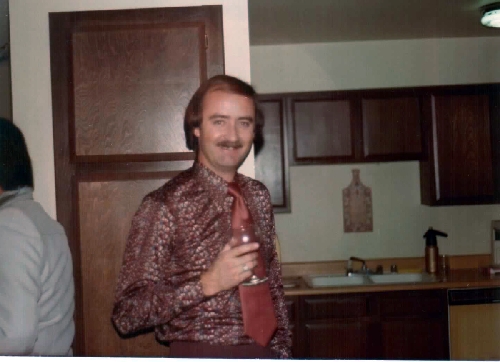

George Monahan had given a test ride to a man who expressed an interest in buying the family's van. The dentist was robbed of $2 and shot in the head.

Jim Monahan was just 12 when his father was killed.

Samuel Howard was arrested five days later in Downey, Calif. On at least 20 previous occasions, police said, Howard had pretended to be a customer and requested test drives from used car salesman and others who were selling cars. He then would rob them.

On May 4, 1983, Howard was sentenced to die for murdering 39-year-old George Monahan.

Howard, now 61, continues to be incarcerated at Ely State Prison. Nevada provides him free room, board and medical care -- even airlifting him to UMC in Las Vegas when he slipped into a coma in 1991.

Letters he has written have been posted on Web sites for advocates for prisoners. He professes to be a born-again Christian.

"God will help you make the right choices, but he will not help you make the wrong ones," Howard wrote in a letter in which he warned teenagers against drugs and premarital sex. "The choice is yours. You can follow Him now or suffer later. I don't want you or anyone to make the dreadful mistakes I have made in my life."

But Jim Monahan, now a marketing executive in Boise, Idaho, has never received a letter of apology from Howard. Monahan even wrote him last year.

"I just wrote 'You killed my dad. I am ready to start a dialogue with you.' You would think if he is a born-again Christian that he would be remorseful."

Monahan grew up without a father. He continues to grieve.

"My mother has died. Most of my dad's friends have died, and he continues to live," he said. "Why? He has outlived almost everyone in my family. It makes no sense financially for the state of Nevada to keep paying for these guys to stay alive. Executing Howard will not bring my father back, but may bring a small amount of closure to me and my family."

Howard is one of 80 male prisoners on death row at the Ely prison. Twenty-nine of them were given death sentences before 1990. Seven of them have been on death row longer than Howard, including Edward Wilson, who has been waiting to die since 1979.

Last year Assemblyman Bernie Anderson, D-Sparks, introduced a bill to require the state to carry out a thorough study of the costs of keeping prisoners alive as they file legal appeal after legal appeal in a quest to keep from being injected with a lethal dose of poison.

Anderson did not try to hide his goal. He opposes capital punishment and figured, based on studies in other states, that Nevada could save million of dollars in legal expenses if it abolished capital punishment.

The Assembly approved Anderson's bill, but it died in the state Senate. Several legislators questioned the need for a study because it was clear the cost of paying legal expenses for death row inmates was extremely expensive.

The state of Iowa, for example, found the lifetime costs of incarcerating and paying legal expenses for a death row inmate was $2.4 million, or $900,000 more than it costs for someone sentenced to life imprisonment.

According to the Nevada Department of Corrections, it cost $26,800 last year to house each inmate at the Ely State Prison, the state's maximum-security prison.

Corrections Director Howard Skolnik said he can do nothing to speed up the process that leads to executions because inmates are legally entitled to appeals.

"It is unfortunate the families of victims have to wait through the process for any form of closure, but our responsibility is to carry out the sentence and respect the offender's right to appeals," Skolnik said.

Michael Pescetta, an assistant federal public defender in Las Vegas, represents Howard and has represented other inmates on death row. Pescetta declined to comment about Howard's case.

But during the hearings on Anderson's bill, he gave legislators a good outline on why penalty cases are so expensive:

After a District Court judge has sentenced someone to die, the prisoner automatically receives an appeal to the Supreme Court, which must conduct an "en banc" review of the conviction by all seven justices.

Then if he loses, the inmate can petition for a new hearing through writ of habeas corpus proceeding. Then he can appeal to the federal district court. If he loses there, he appeals to the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. From there, he can appeal onto the U.S. Supreme Court.

Usually, the federal courts send the case back to the state for further district court and Supreme Court reviews because the inmate did not exhaust all his available state remedies.

What often happens is the inmate charges he did not receive effective counsel, the judge at his trial did not properly advise the jurors or that one or more of the aggravating factors used to sentence him to die were inappropriate.

Pescetta also told legislators that Nevada has executed 12 inmates since the death penalty was established in 1977. Of that dozen, only one was executed involuntarily. The remainder decided to give up their remaining appeals. Records show that 143 people have been sentenced to death in Nevada since the current death penalty law was passed. With 80 men still on death row, the figures mean that 51 either died while in prison or have had their sentences reduced to life imprisonment or to less.

At least three, Roberto Miranda, Victor Jimenez and Dwayne Stevens were freed through the efforts of lawyer Laura FitzSimmons, who presented evidence of their innocence.

Miranda, who came to the United States in 1980 from Cuba as part of the Mariel boat lift, was set free after 14 years on death row.

In 2004, Miranda received a $5 million settlement from the Clark County public defender's office to settle a lawsuit he had filed.

Jimenez spent 10 years on death row before being granted a new trial on police misconduct charges. Rather than face another trial, he made a deal to plead no contest to second-degree murder and win his release from prison for time served.

Stevens was on death row for eight years before winning a new trial at which he pleaded guilty to second-degree murder. He eventually was released.

FitzSimmons wishes there were some type of "foolproof computer" to determine if someone charged really is guilty. As long as there is not, she said there is a chance that an innocent person will be executed.

"It's not a perfect system for anyone, especially for the victims, for the victims' families," she added.

Assemblyman John Hambrick, R-Las Vegas, said there is nothing legislators can tell Monahan to reduce the grief he feels over his father's death.

"It is not justice when the families of victims have to wait 30 years for closure," said Hambrick, a former member of the U.S. Secret Service. "But states like Texas (where 24 inmates were executed last year) don't seem to have the same problems as we do."

Assemblyman Ty Cobb, R-Reno, opposed Anderson's bill in part because there was no discussion on how having capital punishment actually may reduce trial costs.

With a capital punishment hanging over their clients' heads, defense attorneys may be more apt to plea bargain to a reduced offense, Cobb said. That step can avoid trial costs.

"Having it on the books is a means to encourage a plea bargain," Cobb said.

That said, Cobb added that the long appeal process allowed death-row inmates was something pushed on the states by the courts.

"It is not something we can change," said Cobb, a lawyer.

Jim Monahan knows about mandatory appeals, legal costs and the costs of incarceration.

But that hasn't made it easier.

He remembers returning to school three days after his father's death.

"I never saw a counselor. I probably should have. I could have gotten into a lot of trouble in high school. I didn't."

He moved to Oregon after high school and then to Idaho. He only returns to Las Vegas for reunions of the Bishop Gorman Class of 1985. Then invariably the talk turns to his father, the murder and Howard.

"I have some high school friends who are lawyers and watch what is happening with him," he said.

Monahan has three young children. They sometimes ask about what happened to their grandfather.

He won't tell them yet, he said. They are too young to understand.

"It is not going change anything if that guy is alive or dead. I know that. But I would rather see him eaten by rats than to die peacefully."

Contact reporter Ed Vogel at evogel

@reviewjournal.com or 775-687-3901.