Why not use cybernetics?

Want to improve education? Use cybernetics.

Cybernetics is not some science fiction, futuristic, complex gizmo festooned with blinking lights, but a concept as old as sentient beings. The term was coined in 1948 by mathematician Norbert Wiener and taken from the Greek word for "steersman." It means nothing more than establishing a course by observing the surrounding environment and steering accordingly, whether this is done by a human or an automated machine -- as was first done during World War II when aircraft and submarines pinged their surroundings with radar and sonar.

The principle can be applied to how you choose your route to work, your career, your mate or your child's education. Adapt by using the data available.

In his State of the State speech, newly inaugurated Gov. Brian Sandoval called on school administrators to "rely heavily on student achievement data in evaluating teachers and principals" and to "improve accountability report cards and provide more parental choice."

He also called for the end of social promotion for those students who can't read at grade level. This dovetailed with the proclamation he signed after being sworn in that calls on Nevada's schools "to develop and administer a new common assessment that will gauge the reading proficiency of second graders."

In an op-ed piece penned for the Review-Journal, newly appointed Clark County Schools Superintendent Dwight Jones sounded a similar note, promising to make accountability a key objective. He called for use of a growth model, "which identifies not only the student's proficiency level, but how much growth is needed and growth over time."

He said the district is working on an easily navigable online resource that will allow the public to compare results on a school, district or state level.

The future is now.

Much data of that nature is already available at ccsd.net and at nevadareportcard.com.

Additionally, lurking on the networked computers at the Clark Country School District's office of Assessment, Accountability, Research & School Improvement is a vast storehouse of student achievement data -- everything from the interim assessment test given three times a year to every student from kindergarten through middle school, to various criterion-referenced tests that determine if a student has learned the assigned material.

From a desktop computer an administrator can access the test results for any student in the district, as well as the aggregate achievement level of the students of any teacher, of any grade in any school, of any school or group of schools. And that's where cybernetics comes in. Merely having the data is only half the battle.

Sue Daellenbach, the assistant superintendent for the assessment office, has been providing training for schools that request it on how to analyze interim assessment test results and adjust the teaching method to account for areas in which individual students need extra help.

"Teachers get together by grade level or subject areas and then they look at how they group students to reteach things or how maybe one teacher teaches one standard really well," Daellenbach says. "So that teacher can either share how she teaches that with the other teachers or she can maybe take those kids and teach it."

The information is also being made available to parents. Aaron Markovic, a coordinator in the Instructional Data Services Department of Daellenbach's office, had just recently attended a parent-teacher conference in which the interim assessment results were addressed.

"A lot of this information parents might not be familiar with what the specific objectives look like," Markovic says, "so what the teacher then does is actually go through this assessment with me and opens up to the items where my child missed. So she actually reads a question with me, tells me what my child selected and then I have an understanding where I can help at home by looking at the types of skills that they need help with."

On a computer Daellenbach and Markovic displayed the Instructional Data Management System, which Clark County and a private firm developed to simplify access to student data.

Daellenbach noted, "Parents get their own children. Principals can pull it up by teacher, by school, by grade. So they can know where their weaknesses are." A principal can take beginning and ending assessment scores and see where a student or a teacher might need improvement.

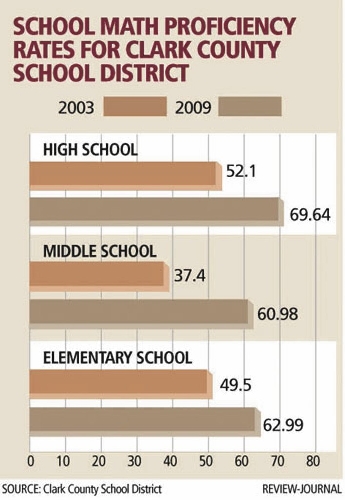

Daellenbach and Markovic think the feedback the data is providing may be a contributing factor to the rise in math proficiency rates in elementary, middle school and high school districtwide over the past decade (see graph.)

One thing about using the "growth model" identified by Jones is that it answers one of the criticisms of the No Child Left Behind Act, which is that all the emphasis is on making every subcategory of minority, English language learner, special needs child, etc. merely proficient. In a growth model, Daellenbach explains, not only do you need to move this group or that group up but also your high achievers.

Asked if there were a principal who is putting the data to good use, Daellenbach and Markovic singled out the new principal at Lamping Elementary in Henderson.

"Robert Solomon is invested in it, gets his staff involved," said Markovic. "All have a very clear vision. His first full year at Lamping, he's been pulling data for three years for his teachers. He likes to look at where students scored before they were in a teacher's class and look at that same student and where they ended up at the end of the year.

"It's not enough that your students are above that bar, did you actually take your students further during that time they were in your classroom?"

This was another area addressed by Jones in that op-ed. He wrote that educators need to be "treated as are their professional colleagues in other fields. They can earn salary increases commensurate with results: their students' achievement. ... provide professional development to those struggling, and remove from the classroom those found to be ineffective."

Daellenbach noted that school systems around the country are starting to look at pay for performance and what kind of achievement data is good for that.

"In all fairness," she warned, "those tests were not written to evaluate teaching. ... Anytime you get into pay for performance there has to be many areas you look at, not just one test score. It's coming. ... The goal is to make it fair, accurate and valid."

Of course the complaint from teachers is that evaluations based on student achievement punish teachers assigned to poorer schools where students tend on average to lag behind their counterparts in more affluent schools with more active parents. Fairness might be found in not judging whether a teacher's students achieve proficiency but whether those students grow in achievement over the year.

At Lamping Elementary, Solomon enthusiastically pulls a three-inch thick binder from a shelf and pores over the data he's assembled in various formats, explaining the difference between summative and formative testing data.

The governor's end of the second grade test is summative, telling whether a given child has achieved the required level of competence to be able to tackle the next grade.

But Solomon is also concerned with formative data that helps him as a principal determine what has worked and what needs tweaking.

"We may have a group, despite what we are doing, they're still below grade level, not making the progress they need," Solomon explains. "So we're going to have some small intervention group, and we're going to be pulling those kids whether that's within the classroom or an outside location or with a literacy specialist or with a teacher in the back of the room. And they're going to get more of something specific than the other kids get, because they are not making the same progress as the other kids. Using data to track that progress helps me ensure that we're making sure all those kids are getting that intervention if needed and we don't have kids falling through the cracks. So when I look at the data, I'm looking at who is it, according to the data, that needs additional support."

This sounds like a far cry from the industrial-age education model of putting all children on an assembly line of rote teaching and expecting them all to come out Cadillacs on the other end.

Solomon's school is relatively affluent and as such it is relatively high performing -- with a vast majority of its students proficient in reading, math and writing -- well above the district and the state. But he's not satisfied.

"I'm looking at what are we doing to improve," he explains. "How are our high kids getting higher. How are our low kids making progress. So I'm able to look at the depth of knowledge with the level at which that is being tested. So I can go through a document like this and I can meet with third grade (teachers) and say: 'I notice that you've really excelled in these areas but these areas seem to be an overall third grade area that we can improve on. What is it that your grade level can do to address this skill in a different way than you've been doing?' So that's really where the conversation is. That's the formative side. Taking a summative assessment but using it for formative purpose."

Solomon says he and his teachers are looking at data, adjusting as they go along, using interim assessments, using various tests, using chapter and topic tests, using selection story tests -- looking at who's not meeting the mark and reteaching as needed.

Solomon summed up the objective of good teachers and principals, "We are in the business of refining what we do to meet the needs of the kids."

It is cybernetics in action. Take your bearings and correct your course as you go. It is already working in some schools. It should be demanded in all.

Thomas Mitchell is senior opinion editor of the Review-Journal. He may be contacted at 383-0261 or via e-mail at tmitchell@reviewjournal.com. Read his blog at lvrj.com/blogs/mitchell.

SCHOOL DATA

The Review-Journal has posted performance reports on all Clark County public schools, here.

We have also posted online the tasks a fourth grader is expected to perform on a first trimester assessment test, the results of which are shared with parents. Teachers and parents are encouraged to target areas in which a child is lagging. Read it at: lvrj.com/assessment.

Additional data and evaluative material is available at ccsd.net, here and nevadareportcard.com.