McCarran embraces spacious new Terminal 3

For decades, running on a treadmill came with the job at McCarran International Airport.

As fast as new concourses were designed and built, the booming Las Vegas economy drew people to fill them. When they weren't mapping out new buildings, McCarran officials tried to squeeze in more passengers than the terminal's planned capacity.

When the $2.4 billion Terminal 3 opens Wednesday , McCarran will finally have caught up and - for now - even overshoot the mark. At age 59, Randall Walker expects this to be the last major project of his tenure as director of the Clark County Department of Aviation.

The biggest item on his current preretirement to-do list is demolishing the soon-to-be-vacant Terminal 2.

"With Terminal 3, McCarran is several steps ahead of the growth curve," Walker said.

With the art installations, shiny terrazzo floors and design touches such as curved rows of seats in gate areas, descriptions involving adjectives like "world-class" are inevitable.

What counts is what travelers won't see. With the soaring dimensions of the building, nearly a half-mile long, a second security screening area in reserve and room to add restaurants and shops beyond the initial 16, there won't be the peak-time congestion common in some parts of Terminal 1. And even Terminal 1 will see some relief when five domestic airlines move to T3 on July 23, leaving empty at least 20 T1 gates once interior renovations finish in Concourse C late this year.

All told, McCarran will be able to handle 53 million passengers a year without more work on runways or terminals. Last year the nation's seventh-busiest airport saw 41.5 million passengers come and go, still some 6 million below the peak in prerecession 2007. McCarran is second to Los Angeles International Airport for origination and destination traffic, or the number of travelers who start or finish their trip there, not just change planes.

Passenger counts are inching up at a single-digit percentage rate as airlines preach and practice capacity discipline, the industry term for keeping a tight rein on flight schedules to support higher fares and deal with volatile fuel bills.

Air carriers objected to awarding the general contract for Terminal 3 in July 2008, as the economy plunged into recession and oil prices soared above $140 a barrel. Because of the difficult economic outlook, they argued for putting the project on hold after a decade of planning. The county went ahead anyway with Perini Building Co. of Henderson as the main contractor and PGAL of Houston as the architect.

"I know that some people regarded this as a WPA project just to create employment," said Michael DiGirolamo, an independent consultant and former deputy executive director of Los Angeles International Airport, referring to the Works Progress Administration projects that were part of President Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal in the 1930s. "In the long run, I think there may be benefits, especially going ahead with the international part."

Michael Boyd of Boyd Aviation Group in Evergreen, Colo., added, "Those gates (in Terminal 1) are probably going to remain empty for a good 18 months. But that's about 18 seconds in airline time. McCarran is going to grow."

Even so, McCarran management has frozen all work on a second airport once envisioned for Ivanpah, about a dozen miles north of Primm.

In the short run, airlines will pay the price for Terminal 3. Cost per enplanement, the industry benchmark that calculates how much a carrier pays in airport fees and rent for each passenger, is estimated to hit a record high of $12.06 at McCarran during the coming fiscal year, a 160 percent increase from 2006.

Many airports, including McCarran, are largely self-supporting. They receive funding from federal ticket taxes, but no operating subsidy from local governments. Airline use fees, parking garage revenue, rent from tenants such as gift shops, restaurants and rental car companies pay the bulk of terminal construction and operating costs.

Enplanement costs haven't grown just because of T3's construction debt. Falling passenger counts in recent years, driven by factors such as the economic recession and US Airways' decision to dismantle its hub here, require that fixed and day-to-day costs be spread over a smaller crowds. Because airlines sometimes reduce service or even skip airports with high fees, airport managers pay attention to the number.

"We have always been concerned about cost per enplanement," Walker said. "It is important, but not the overriding factor in determining airline service,"

Yet it was important enough for McCarran to spread the collection of $50.7 million in airline fees over time, starting in 2008, to ease sticker shock.

With cost per enplanement at $12.06, McCarran is in the middle of the pack among big airports, falling between low-cost hubs such as Atlanta and Dallas-Fort Worth and high-priced venues in New York and Miami. It was one of the cheaper major airports.

"Besides Allegiant (Air), I don't think Las Vegas' cost per enplanment is at a level where it will make a difference," said Boyd.

Although regarded as a specialty carrier, Las Vegas-based Allegiant Air, a subsidiary of Allegiant Travel Co., has grown rapidly for several years and now ranks fourth in McCarran's traffic roster.

"We still believe there's an opportunity for us to continue growing profitably," the company said in a statement. "Having said that, we believe lower costs would allow us to grow faster and we appreciate the airport administration's efforts to control costs where they can."

Walker said cost per enplanement bounces up with a new building, then declines as passenger counts grow.

"Any additional costs are always a concern for airlines," DiGirolamo said. "All in all, the $12 level is not a problem for Las Vegas. But if the economy goes south, the airlines will look at it more closely."

Contact reporter Tim O'Reiley at toreiley@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-5290.

Terminal 3 Guide

An interactive guide to Terminal 3

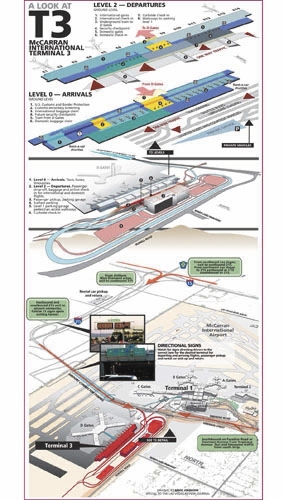

A look at McCarran's Terminal 3

What's Next?

• Wednesday: Terminal 3 roadways open at 5 a.m. A Virgin Atlantic flight from London will be the first arrival. Copa Airlines will launch nonstop service between Las Vegas and Panama City, Panama. Korean Air and British Airways also move on the 27th.

• Thursday: The rest of the international roster moves: AeroMexico, Air Canada, airberlin, ArkeFly, Condor, Philippine Airlines, Sunwing Thomas Cook, VivaAerobus, Volaris, WestJet, XL Airways.

• July 31: Domestic carriers Alaska, Frontier, Virgin America, JetBlue and Sun Country move from Terminal 1.

• Aug. 22: United and Hawaiian to relocate baggage and ticketing functions to Terminal 3 with gates still in Concourse D, connected to Terminal 3 by an underground tram.