Long-ailing UMC aims to alter image, add revenue

Hospitals typically spend millions of dollars a year marketing themselves. University Medical Center of Southern Nevada gets much of its name recognition for free.

Whether in written or televised news accounts, UMC's trauma center often serves as the backdrop for shootings, stabbings and other major incidents . Two weeks ago, IndyCar racer Dan Wheldon died there after a 15-car crash inflicted head injuries beyond treatment.

To UMC Chief Executive Officer Brian Brannman, the trauma center's prominence helps showcase some of the county-owned hospital's strongest assets.

"We think we can take care of a lot of catastrophes and accidents with excellent results," said Brannman, who took his post July 1. "A level one trauma center is essential for a community this size."

But Las Vegas medical industry consultant Jack London of London Medical Management said the video cameras frequently clustered on the curb outside the trauma center add an association of murder and mayhem to UMC, which already is widely regarded as a facility for low-income patients. As a result, people with insurance and the ability to cover copayments and deductibles look elsewhere.

"That's a blunt description, but it is reality," London said. "When people have elective treatments, UMC doesn't come into the mix."

The view that comes closest to the mark could loom large in deciding whether UMC management can significantly slash the chronic operating deficits covered by county taxpayer subsidies. Brannman and others familiar with UMC agree that attracting more paying patients and reducing the share covered by Medicaid or who are indigent will be essential to financial viability.

"In my mind, you can't cut (expenses) to get there," he said. "Revenue is the heart of it."

COST CUTS HOPE TO STOP RED INK FLOW

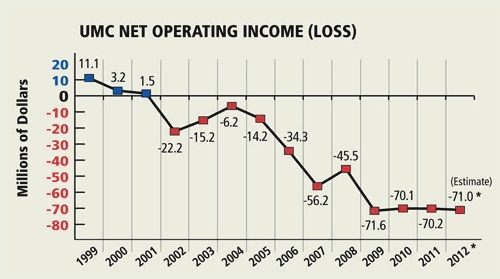

The budget for University Medical Center's current fiscal year projects a loss of $71 million, the fourth consecutive year at that level at revenues of $492.3 million. Since 2001, the last year UMC posted a surplus, the hospital's cumulative loss has mounted to

$405.8 million.

As several cost-saving and revenue-generating programs are put into effect, many resulting from a study of hospital operations by FTI Consulting, Brannman estimates the loss could drop to $50 million or less in two years. How the new federal health-care finance law will change the equation, if the U.S. Supreme Court upholds its legality, remains an unknown.

Even if the financial improvements fall into place, the deficit would still run at politically touchy levels. Clark County Commissioner Lawrence Weekly, who doubles as the chairman of UMC's board, acknowledges that county employees have grumbled about UMC subsidies as falling tax revenues have necessitated pay cuts and layoffs in numerous departments.

"We need to change the attitude of those who feel like, 'Let's give up the hospital. It needs to go away,' " Weekly said Oct. 5 during a hospital board meeting. "I don't agree with that."

But if the losses cannot be tamed down the road, a drastic restructuring could ensue.

"It's going to come to a point where there aren't any more options," London said. "Patience has worn thin."

To a large degree, the financial ills at UMC mirror those of public hospitals across the country.

"Of all the different types of hospitals, public hospitals have the most precarious financial situations," said Richard Gundling, a vice president of the trade group Healthcare Financial Management Association.

He ticked off public hospitals in Denver and Dallas as having righted themselves financially, but added, "It is a very short list."

A private chain took over the public hospital in Fresno, Calif., said Kevin Kennedy, a principal in the Seattle office of ECG Consulting, yet the subsidies continued unabated.

WEIGHED DOWN BY MANAGEMENT WOES

Some of UMC's wounds were also self-inflicted through management problems that came to a head during the three-year tenure of former CEO Lacy Thomas, who was fired in 2007. Even now, Brannman does not swear by the published financial results from that time because they were created through forensic accounting, which tries to create books after the fact because the originals were so unreliable.

The management turmoil came when patients were turning increasingly to new or enlarged competitors in the valley's outlying neighborhoods, stinging UMC's bottom line.

The expense of running UMC has dropped in the past couple of years, as patient loads have dropped. In fiscal 2011, which ended June 30, the expense fell 3.7 percent.

Also, management has implemented several expense-shrinking initiatives, such as reducing accounts payable to obtain better terms from vendors; eliminating positions; freezing or cutting pay; renegotiating physician payments; buying fewer types of surgical implants; and even opting for reusable instead of disposable pillows.

"Expenses have been managed reasonably well," said Harry Hagerty, a retired executive who heads the finance committee of UMC's volunteer advisory board. "I don't think there is a lot of additional fat to cut."

County commissioners voted Oct. 5 to increase nursing pay immediately to make it competitive with other valley hospitals, some of which have paid the contract termination penalties of UMC nurses to hire them.

Nevertheless, the losses have persisted because revenues have also dropped. In the past year, that meant a 4.2 percent revenue decline to $469.2 million, requiring a $65.4 million county subsidy plus some smaller sources to cover the deficit.

During calendar year 2010, state statistics show, 27 percent of UMC's total bills were incurred by the Medicaid program for the low-income, double the Clark County average. Only three other hospitals were as high as 10 percent.

The Nevada Hospital Association calculates that Medicaid pays 58 cents for every dollar of actual expense, far less than private insurers.

Also, UMC had to write off $253.3 million in either bad debt or charity care, more than double any other Las Vegas hospital. By contrast, the consistently profitable Summerlin Hospital Medical Center lost $41.2 million in the two categories.

Thus, Brannman has placed a top priority on bolstering what industry officials term the payer mix.

Further, said Gundling, many private hospitals offset the hits they take on charity care and Medicaid by raising rates on patients with insurance. But, he added, a relatively small insured clientele limits or even eliminates this option.

IMAGE ISN'T EVERYTHING

Brannman conceded that the public's impression of UMC is molded by Hollywood images of public hospitals in places like Los Angeles and Chicago where gurneys line the hallways with people who wait hours to be seen by a doctor.

"We're not like that," he said.

He will work to persuade doctors, who control the majority of patient placements, to send people to UMC based on the quality of outcomes. Federal policy and private insurers have increasingly based payment on how a case turns out, with penalties for high infection rates or readmissions.

He hopes to build "centers of excellence," or specialties in which UMC could tout an edge over rival hospitals, such as oncology, cardiology and transplants.

However, Hagerty noted, recruiting doctors over the years has not been easy because "some of the facilities have degraded" after years of too little investment.

To improve recruiting and improve the effectiveness of management, he is among those advocating a new governing structure that would create much greater autonomy for UMC even if it remains county-owned. Many significant decisions and contracts now require county commissioners' approval.

"You have to be able to make difficult decisions without having elected officials get involved and overturn them," he said. "And you can't seek tens or hundreds of millions of dollars in donations in the current format."

Furthermore, Kennedy said, most every other hospital also pushes its star programs and quality of care.

"The idea of going after better-paying patients is not new to health care," he said. "The ability of a public hospital to compete on that basis is probably very limited."

The hospitals that have risen on the valley's outlying areas have adopted private rooms as the standard. By contrast, about half of UMC's 541 beds are in shared rooms.

"That absolutely makes a difference in the overall user experience," he said. "Patients look at factors such as how shiny is the lobby, how clean is the facility and private rooms."

London downplays the influence of patient preferences, but believes UMC needs another major initiative such as the network of 10 Quick Care clinics spread throughout Las Vegas.

"That was a brilliant move from the outset," he said, "and they need another one."

He thinks such a move might come in the steps UMC management is taking to tighten ties with the University of Nevada School of Medicine. Many teaching hospitals have developed the specialties that attract a broad swath of paying patients and run at a profit, he said.

IMPROVING EFFICIENCIES

Besides changing the patient mix, UMC management has started installing the $30 million first phase of an electronic health records system, ultimately to replace the hand-scribbled notes in folders that have filled hospital shelves for decades. With that, and better training of physicians' staff, Brannman hopes to boost revenues by putting the correct codes on patients' requests for reimbursement.

Medical procedures are now cataloged by thousands of numerical codes. But filling out a form with a code for a simple surgery instead of one in which complications resulted can cost a hospital thousands of dollars.

Whether UMC is letting nonpaying patients off too lightly provoked an Oct. 5 outburst from Clark County Commissioner Steve Sisolak.

"For two-and-a-half years, I have been preaching that you're not collecting what you should collect," he said. "I've met with folks. I've talked with folks. Nothing ever happens. We're leaving money that's not collected."

Brannman said collection efforts, which he vowed would be increased, had been delayed by vacancies in top management of the department.

"I need a captain for this team," said Brannman, who was a rear admiral in the U.S. Navy before he retired to become UMC's chief operating officer in 2008.

Now, he has to try to boost the hospital's appeal.

"At the end of the day," he said, "it is up to us to create the kind of place where people want to go for medical care regardless of the pay source."

Contact reporter Tim O'Reiley at

toreiley@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-5290.