Surprise! Some Nevadans, once jobless, hit with overpayment notices

Renee Woitas assumed the last time she would hear from the Department of Employment, Training and Rehabilitation was when she received her last unemployment check in September 2021.

Then in December, she received two separate notices from DETR stating that she owed a total of $23,346.

Like many self-employed people in March 2020, work for Woitas’ auditing consultancy quickly dried up.

In May 2020, she began receiving the highest possible weekly benefit of $469 through the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance program, a temporary federal program designed to support self-employed and gig workers who don’t qualify for unemployment insurance benefits. The program helped financially support Woitas, even when her husband died of COVID-19 in July 2020.

But the letters she received Dec. 14 and 15 stated she was ineligible for the amount she received, citing a “base period wage decrease.”

“I have a little in savings, but $23,000 is a lot of money and they come out of nowhere,” Woitas, a Las Vegas resident, said. “If I would send a bill to somebody that was 14 months after I did business with them, they wouldn’t pay me.”

DETR was flooded with an unprecedented number of claims — 1.1 million for PUA claims through 2021 — during the pandemic, with the state’s unemployment rate reaching a peak of 30.6 percent in April 2020.

Adding to the demand was the rollout of several new pandemic-related unemployment insurance programs like PUA. The department paid nearly 8.1 million weeks of unemployment insurance in 2020, according to the Department of Labor. In contrast, the state paid 783,478 weeks in 2019.

The result was an estimated $1.4 billion in overpayments, and about $644 million were fraudulent while $784 million were attributed to nonfraud improper payments, officials said. The agency recovered about $114.4 million in fraud payments as of December 2022, according to a public records request.

DETR determined at the end of 2022 that it overpaid 84,357 PUA claimants between March 2020 and September 2021, and 64,452 claimants under the traditional unemployment program between March 2020 and February 2023.

Many Nevadans have been caught off guard by their overpayment notices, and those who have tried to inquire or dispute the determination describe it as a drawn-out, unclear process.

“It’s really difficult because they don’t communicate very well,” Woitas said. “They’ve shown all the way along that they really had no idea what was going on and they were shooting from their hip. I don’t have a problem with that. But you paid me and you determined how much I should get, not me. I didn’t go in and say I needed some amount from the information I gave you.”

How overpayments occurred

Overpayments can stem from a variety of instances such as fraud, errors on forms and omissions made by the claimant. DETR also mistakenly gave some claimants more money than it should have, DETR Director Christopher Sewell said.

“When you go from 3 percent unemployment to over 30 percent unemployment — our system was overwhelmed,” Sewell said. “We were trying to push out as much money to help as many families as possible and in that case, we made mistakes.”

For the PUA program, claimants often reported more income than they had, Sewell said. The department had to take them at their word because the state’s lack of an income tax meant there was no way to independently verify the income through the Nevada Department of Taxation. Meanwhile, traditional unemployment insurance is able to verify a claimant’s income through its employer.

Because PUA was created for self-employed workers, it had to use multiple forms of self-reporting to verify a person’s eligibility. The agency faced criticism when it paid then later froze unemployment insurance benefits for more than 9,000 PUA claimants in 2020, after a lawsuit was filed in May 2020 by independent contractors and self-employed workers. One of the reasons for the delay, DETR said at the time, was determining the correct eligibility for claimants, but a judge ordered the department in July 2020 to finish paying the claims anyway, with some exceptions.

Others may have received overpayment notices regarding a base period wage decrease, which likely stemmed from the claimant seeking benefits based on their net income instead of gross income, which the Department of Labor requires, Sewell said.

Las Vegas resident Letitia L’Heureux, who co-runs a live entertainment business with her husband, said her PUA overpayment notices cited a base period wage decrease. She received two notices in December stating that she owes a total of $21,560 for benefits received between March 2020 and September 2021.

“I can tell you I don’t have that,” L’Heureux said. “We used every last little bit, plus whatever we had in our savings, because of our company’s overhead at the beginning of the pandemic.”

L’Heureux said she’s unsure how DETR determined that figure. Her husband, with whom she jointly files taxes, received the same benefits and filed similarly but has not received an overpayment notice. She filed for an appeal on Jan. 11, 2023, and nearly three months later, April 17, received a notice that she has a telephone hearing next month.

Waivers and appeals

Claimants can appeal overpayment notices if they’re unable to pay. To receive a waiver, they must provide DETR with information, including earnings from the last two years, that show it would create significant financial hardship to repay the benefits.

The department estimated it’s waiving about 10,000 claimants, or $4.5 million in overpayments. There are still an estimated 6,000 waivers to process, Sewell estimated.

He said claimants should start by submitting a waiver request online and if the agency is at fault it will automatically waive the balance. There is no cap on waivers.

Claimants can also appeal if their waiver request was denied. Claimants are allowed to have legal representation for the appeal, often a telephone hearing in which an appeals referee allows the claimant to provide testimony, witnesses and documentation to support their case. The referee then issues a written decision — usually within two to three weeks of the hearing, according to DETR’s appeals handbook.

The claimant can appeal the referee’s decision to the Board of Review at the department’s appeals office, which revisits the issue through written or oral arguments, though it can decline to review the appeal all together. If the claimant loses its appeal or the board refuses to review it, they can petition for a judicial review, according to the handbook.

Sewell said there are 32,000 claims in the appeals process and that it could take until December to clear them out.

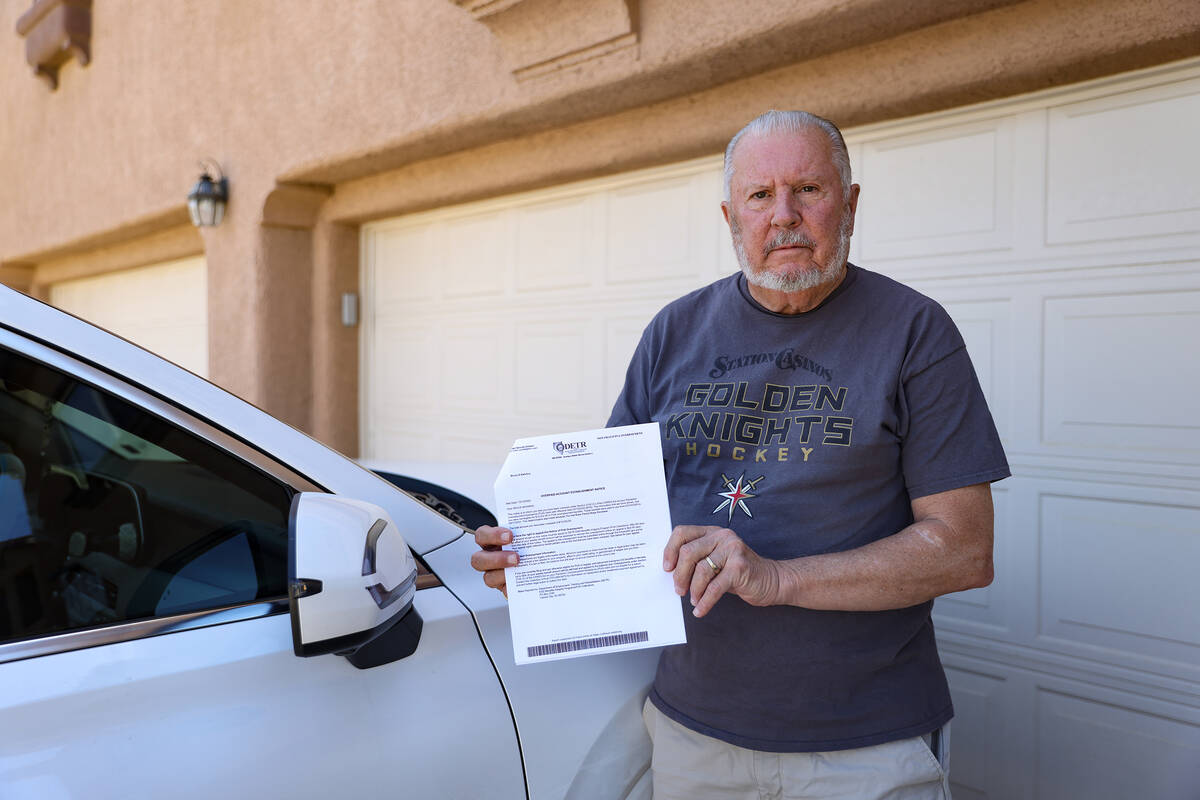

Henderson resident Bruce Kehring said DETR determined he owes the agency $10,032 because of a “base period wage decrease,” after he received his last PUA benefits in September 2021. The former ride-share driver appealed and said it took five months to be notified of a hearing date.

“What bugs me is they don’t give you any details and they say it was an overpayment. Why was it an overpayment? What did they claim (decreased)?” he said.

Kehring said the lack of detail makes it harder for him to prepare for his hearing. He said he doesn’t plan to hire a lawyer because of the cost, and instead, he plans to submit all his documentation that he saved since his claim started.

“I should hope that should be sufficient,” Kehring said.

Cutting into the backlog

DETR said its significant backlog is attributing to delays. Meanwhile, there are roughly 16,000 new claims waiting for its first determination, Sewell said.

The agency’s approximately 13-person team is working on claims while it looks to hire third-party contractors to help address the appeals backlog.

Sewell also hopes to hire more investigators, but because the job is technical it often requires someone with legal experience to do the work, making it more difficult to recruit.

He’ll be watching over the backlogs — the oldest claim awaiting determination is from January — to make sure the agency “doesn’t make any more mistakes.”

“It was a tough time for everybody, and we need to make sure that the people that used that money to keep themselves in a home or an apartment and keep their mode of transportation and food on the table (apply for a waiver) — that’s what those waivers are for,” he said. “We can process those and not be the big bad government and take away money you needed.”

McKenna Ross is a corps member with Report for America, a national service program that places journalists into local newsrooms. Contact her at mross@reviewjournal.com. Follow @mckenna_ross_ on Twitter.