Study of body cams shows drop in use of force by Las Vegas police

Researchers said a yearlong study into the Metropolitan Police Department’s use of body-worn cameras showed a decrease in police misconduct, complaints and use of force.

“They say a picture is worth a thousand words, and in law enforcement, that picture — or video in this case — is often the only thing that can prove or disprove something happened or didn’t happen,” Clark County Sheriff Joe Lombardo said at a Monday news conference.

In 2014, Metro became one of the first large police agencies in the country to equip its officers with body-worn cameras, but pilot testing began in 2011, when the agency was under intense public scrutiny for its use-of-force policies.

Shortly after Metro’s implementation of cameras, UNLV and nonprofit research and analysis organization CNA began monitoring officers to examine how the equipment affected complaints of misconduct, use-of-force incidents, citations issued and number of arrests. The study also looked at costs associated with the cameras compared to the savings created by shortening investigations of officer misconduct.

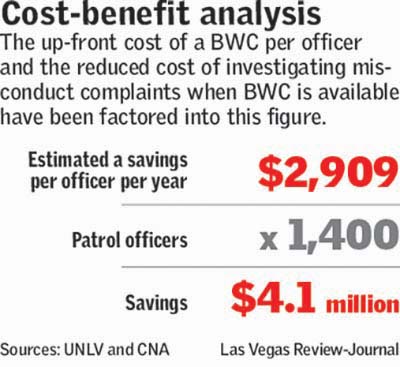

At the time of the study, Metro demographic reports showed that the department had roughly 1,400 officers assigned to its patrol division. Researchers worked from February 2014 to September 2014 to pick from a pool of patrol officers who volunteered to participate in the study.

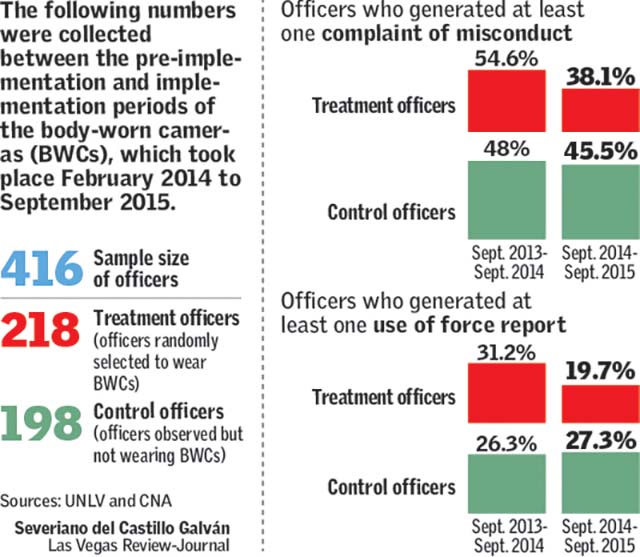

The final volunteer sample included 416 patrol officers. Of those, 218 were randomly assigned to wear the cameras. The remaining officers functioned as a control group and were not assigned equipment, according to the analysis.

Gary Peck, spokesman for the NAACP in Las Vegas, attended the news conference Monday. Peck said he commends Metro for participating in the study and equipping its officers with body cameras, but he expressed concern about how the study was conducted.

“A sample of 400 officers who volunteer to participate is not necessarily a representative sample that tells us what patrol officers more generally are doing,” he said.

Peck said the NAACP also believes Metro’s body camera policy is not precise or stringent enough to ensure officer compliance and accountability.

Dramatic change

After the one-year trial, the research team concluded that body-worn cameras were associated with drops in complaints of police misconduct and use of force, which include the use of Tasers, pepper spray and firearms.

But the data found that the most dramatic change was seen in the use of force, which fell by 37 percent. For officers who were not equipped with a camera during the study, use of force increased 4 percent.

The research also showed that camera-wearing officers were less likely to be reported in misconduct complaints. In addition, the data showed that the use of body-worn cameras was related to an 8 percent increase of citations issued and a 6 percent jump in arrests made.

“These results support the position that (body-worn cameras) may de-escalate aggression or have a ‘civilizing’ effect on the nature of police-citizen encounters,” said James Coldren, a managing director at CNA.

With the results of the study, UNLV and CNA conducted a cost-benefit analysis weighing costs associated with the cameras compared to the savings associated with shorter and fewer misconduct investigations. Coldren said the time it took to resolve a complaint was reduced when video evidence was available.

Controversial incidents

To date, Lombardo said, the department has deployed 1,950 body-worn cameras to its patrol officers, canine units, SWAT and traffic officers.

“The fact that we are using body cameras is no longer an original concept. We are now seeing them put to use at agencies all over the country,” the sheriff said. “What’s unique, however, is how we are using the information to inform our public about the most controversial incidents we deal with, such as officer-involved shootings.”

Footage captured from the department’s body cameras also is being used to find training weaknesses and to strengthen department tactics, he said.

But the Police Department found itself under fire twice this year: after the in-custody death of Tashii Brown in May and again when NFL player Michael Bennett accused the department of detaining him in August because he’s black.

Brown was stunned with a Taser seven times before Metro officer Kenneth Lopera held him in an unauthorized neck hold for more than a minute. The entire incident was captured on camera. But when Bennett was detained during what turned out to be a falsely reported shooting, the involved officer said he forgot to turn on his body camera.

The Metropolitan Police Department’s body camera policy instructs officers to turn on their cameras before attempting to stop someone or responding to a call. Jay Rivera, Metro spokesman, said the detaining officer should have turned his on before stopping Bennett.

In September, in the immediate aftermath of Bennett’s detainment, Lombardo said the involved officer could face discipline for failing to turn on his body camera, but the sheriff would not elaborate on what form that discipline would take.

Lopera has been charged with involuntary manslaughter and oppression under color of office.

Contact Rio Lacanlale at rlacanlale@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0381. Follow @riolacanlale on Twitter. Review-Journal staff writer Blake Apgar contributed to this story.