Art of the heist: Louvre break-in a reminder of infamous Las Vegas burglaries

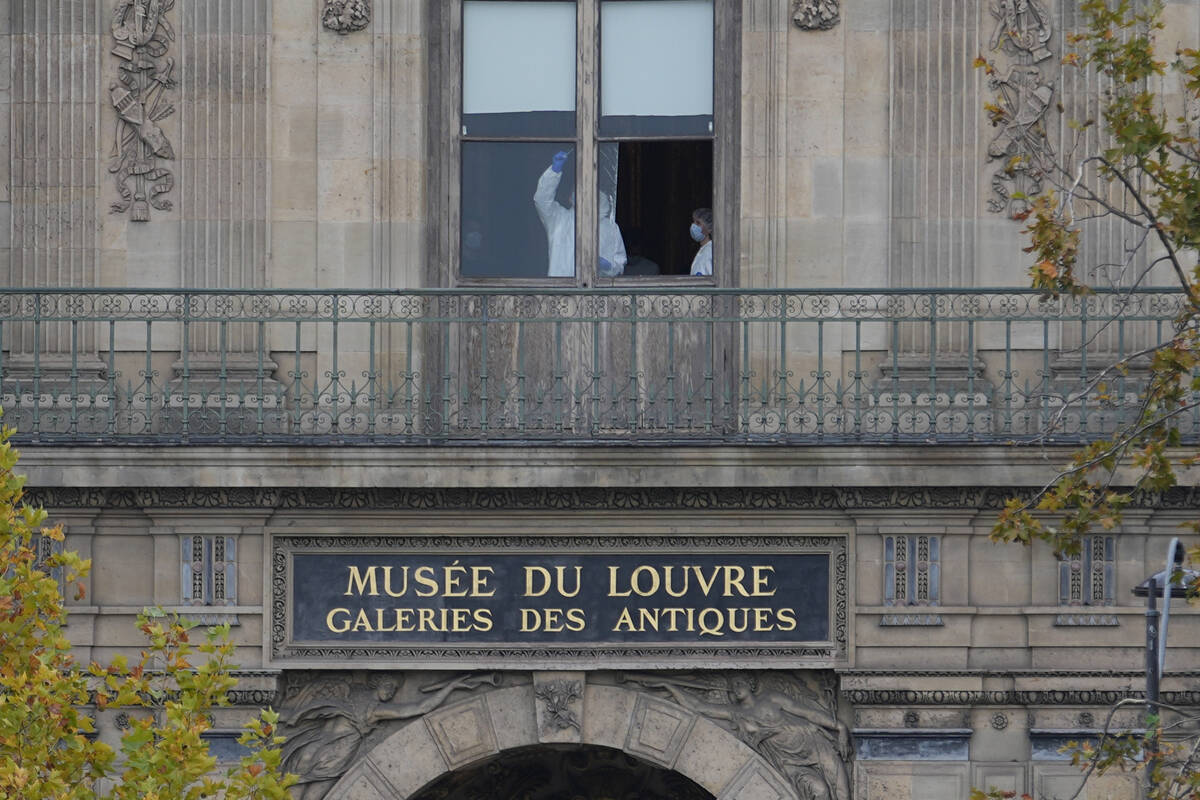

The thieves who stole some of France’s crown jewels from the Louvre last month while dressed as maintenance workers may have been a shock to some, but for the Mob Museum’s Claire White, the brazen tactics utilized in the heist were nothing new.

That’s because Las Vegas has also been the scene of some pretty notorious and headline-grabbing break-ins and robberies over the years. From a high profile diamond theft in the 1950s to the infamous Hole in the Wall Gang’s antics of the 1970s and 1980s to the tow truck-aided burglary of a local Elvis museum in the 2000s, Southern Nevada has also seen its fair share of inventive burglars targeting high value loot.

“Looking at the Hole in the Wall Gang is a super-relevant and interesting comparison to what so recently happened at the Louvre, just because of the way that the Hole in the Wall Gang operated,” said White, director of education at the Mob Museum. “They would break in to private homes and businesses across the Las Vegas Valley by literally busting a hole in the wall of buildings.”

In a span of about four minutes, the Louvre burglars used a vehicle-mounted motorized lift to enter through a window at the Paris museum’s Apollo Gallery, cutting into display cases with power tools before fleeing on scooters with jewelry, brooches and crowns that once belonged to French royalty and are worth an estimated $102 million, according to French law enforcement.

Five suspects accused in connection with the heist were taken into custody late Wednesday, bringing the total arrest count to seven. A French prosecutor told reporters Thursday that at least one more suspect remained outstanding.

For White, the Oct. 19 break-in at the Louvre was reminiscent of the techniques used by reputed mobster Tony Spilotro and his Hole in the Wall Gang, whose robberies of Southern Nevada businesses made them one of the most infamous crime rings of the 20th century, White said.

The Louvre heist isn’t exactly a one-for-one comparison to break-ins Spilotro’s gang was responsible for, or even other notable thefts that have occurred over the years in Las Vegas, said Michael Green, professor and the chair of the history department at UNLV. But with a high concentration of casino chips and luxe shopping centers, security at many Las Vegas resorts may resemble that of art museums with priceless collections, Green said.

“Higher-end museums and casinos, they certainly have the most advanced security technology and support,” Green said. “One thing to bear in mind, though, is the Louvre and the Met (Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York) do close. Casinos don’t.”

Break-in at Bertha’s

The Hole in the Wall Gang’s criminal activity was largely extracurricular from the skimming operations Spilotro oversaw at Las Vegas resorts like the Stardust, Fremont, Hacienda and the Marina, all of which were secretly managed by the Chicago Mafia in the ’70s, White said.

Former Metropolitan Police Department Commander Kent Clifford told state lawmakers in April 1981 the Hole in the Wall Gang had, at that point, stolen more than $500,000 in cash and valuables, mostly by smashing down doors and breaking through walls, according to reporting from the Las Vegas Review-Journal at the time.

Las Vegas wasn’t the only city targeted by Spilotro’s gang. A May 31, 1981, Associated Press report about a series of burglaries around Miami detailed the lengths the Hole in the Wall gangsters would go in order to gain entry to the building they decided to target.

“Typically, the thieves will back up a truck to the wall of a warehouse or business, then burn a hole through the wall with a cutting torch,” the AP reported. “Sometimes the thieves will hack a hole through the wall or tear their way through the roof.”

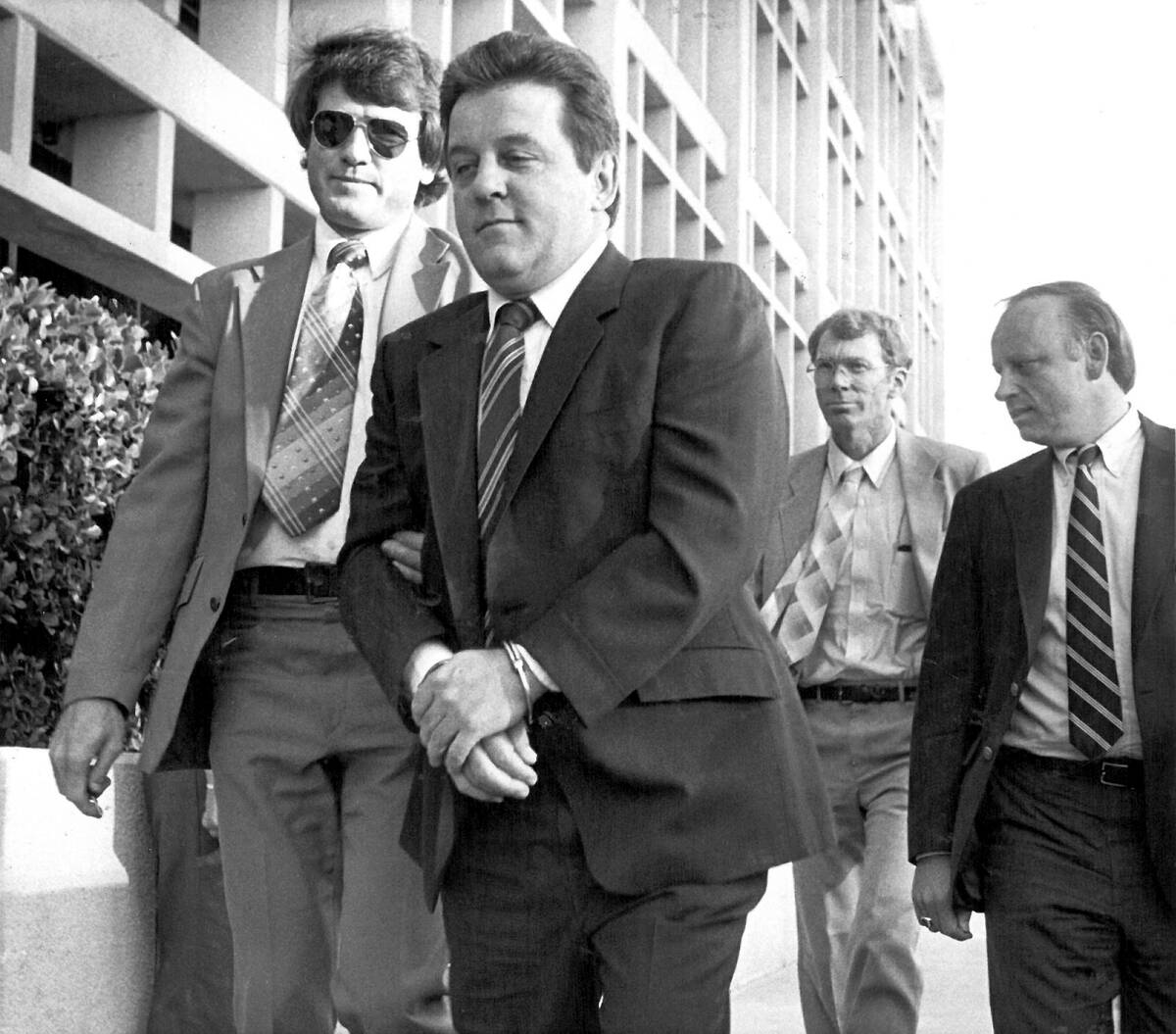

The gang’s fortunes would change drastically in the following months, White said. On July 4, 1981, six members of the gang were arrested as part of a joint investigation between Metro and the FBI after an attempted burglary at Bertha’s Gifts and Home Furnishings, which according to White was a “beloved” local establishment in the area of present day Sahara Avenue and Maryland Parkway.

According to police at the time, the suspects climbed on the roof of the gift shop and used tools to cut a hole over the location where a safe was being kept on the premises. It took nearly two hours to cut the hole into the roof and enter the building, and the suspects caused “extensive damage” to the safe before they were caught in the act by police, the Review-Journal previously reported.

Authorities were able to respond to the scene before the suspects could flee due to an informant, White said. Among those arrested included Spilotro’s childhood friend Frank Cullotta, who after his arrest would become an informant, as well as former Metro detective Joseph Blasko, who was fired by the department in 1978 for providing Spilotro with inside information about police investigations.

Spilotro was eventually arrested for his connection to the heist but eventually beat the charges with the help of former attorney (and future Las Vegas Mayor) Oscar Goodman, the Mob Museum notes on its website. The ordeal not only diminished Spilotro’s standing with his mob bosses in Chicago, but also was a seminal moment for the Mafia’s public perception, White said.

“People loved Bertha and loved this store,” White said. “There really was public outcry that this is unbelievable, that we shouldn’t be allowing these mobsters to come in and target our own.”

Spilotro, who was the basis for Nicky Santoro, the fictional mobster portrayed by Joe Pesci in Martin Scorsese’s 1995 film “Casino,” was found dead along with his brother Michael in an Indiana cornfield in 1986.

Krupp diamond theft

Decades before the FBI busted the Hole in the Wall Gang, they played a vital role in a solving a grand theft that originated just outside Las Vegas.

German-born actress Vera Krupp was dining with a foreman April 10, 1959, at her ranch at what is now the Spring Mountain Ranch State Park when three men forced their way in, ripped the 33.6-carat diamond ring off her finger, and tied the two blindfolded back-to-back with wire from a lamp, according to an FBI webpage.

Though Krupp and the foreman eventually got free, the thieves reportedly made off with the ring, worth an estimated $275,000 in 1959 — or more than $3 million in 2025 — and other valuables. Federal investigators said they were called into the case and, after learning the ring was deconstructed and its pieces zig-zagged across the U.S., eventually tracked the center gemstone to a suspect who was arrested with it in New Jersey about six weeks later.

The pieces were returned to Krupp, the ex-wife of a Nazi industrialist convicted of war crimes, and the ring was rebuilt. Following her death, the ring was sold at auction in 1968 to actor Richard Burton for his wife Elizabeth Taylor, the FBI says on its website.

“Vera Krupp eventually sells the ranch and Howard Hughes owned it,” Green said of the ranch. “Now, it’s a state park where, in the summer, we go and sit on blankets and enjoy the theater and their tours. It’s a historic site and its great.”

Elvis-A-Rama Museum heist

Another notable Las Vegas heist, according to White, occurred in March 2004, when burglars used a tow truck to pry open a roll-up door and get into the former Elvis-A-Rama Museum located at 3401 Industrial Road, near Interstate 15 and Sahara, and left the building with more than $300,000 in valuables once owned by The King of Rock ‘n’ Roll.

In less than two minutes, the thieves made off with 11 pieces of Elvis Presley memorabilia, including his high school ring, a gold-plated pistol and an 18-carat gold and diamond medallion with his initials, according to initial Review-Journal coverage of the break-in. The stolen items were returned in November 2005, though the privately owned museum was sold to the company that owned Presley’s name, image and likeness and later closed.

White said she wasn’t yet working in museums when the Elvis-A-Rama heist occurred, but remembered that the news of it felt like a shock for history buffs and music enthusiasts alike.

“It may pale in comparison to the value of the Louvre heist or some of the biggest heists throughout world history, but Elvis-A-Rama was not a large museum,” White said of the things stolen. “So relative to its collection, that was a huge amount of money.”

The Review-Journal reported when the museum was sold that then-owner Chris Davidson would be granted the right to open another Elvis museum in Hawaii. A LinkedIn profile for Davidson states he is based in Henderson and is the publisher of Speedboat Magazine, which according to its website most recently published in August.

Davidson did not respond to emails requesting comment.

Contact Casey Harrison at charrison@reviewjournal.com. Follow @casey-harrison.bsky.social on Bluesky. The Associated Press contributed to this report.