When planning an Oct. 1 memorial, Las Vegas can learn from other cities

AURORA, Colo. — It has been almost six years. Long, dark years.

But here at this dirt lot about a mile from the Century Aurora 16 theater, where 12 people and one unborn baby were ripped from existence the summer of 2012, the sun is on the horizon.

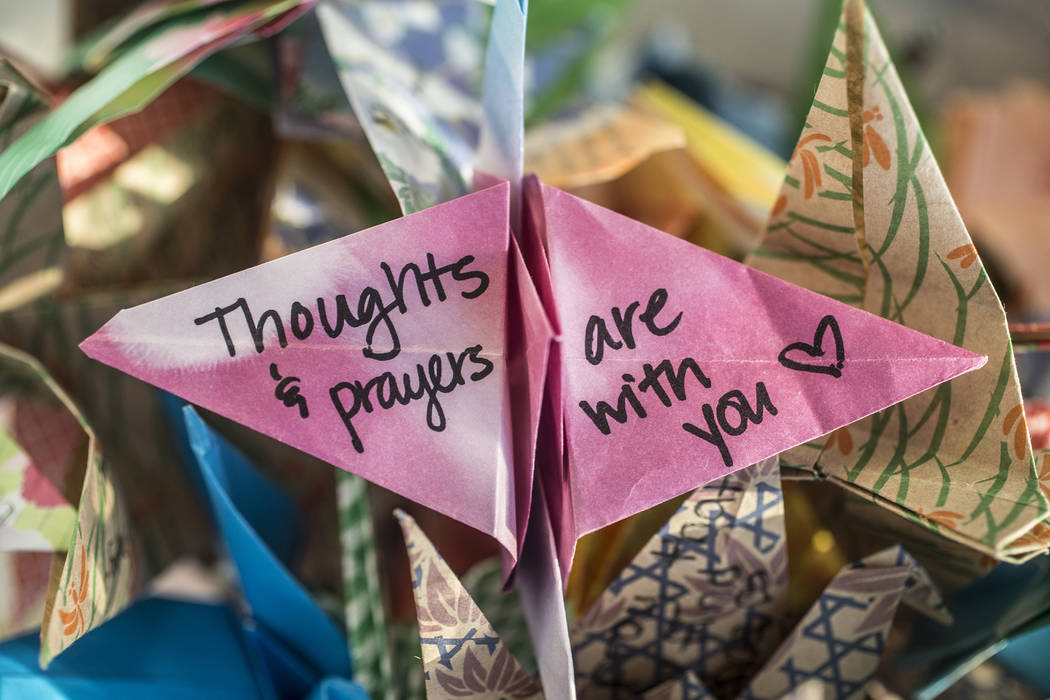

Come July, this plot of land — which is strategically surrounded by a grassy berm so the nearby theater is not visible — will become the Aurora mass shooting memorial. There is still much work to be done: Flowers have yet to be planted, paper-crane sculptures have yet to be installed.

But the plan is in place.

Everything is running according to schedule.

And already, at this spot, it is once again possible for the grieving in this Colorado community to fill their lungs with air without a fight. To pause, reflect and exhale. Because peace seems possible here. Finally.

* * *

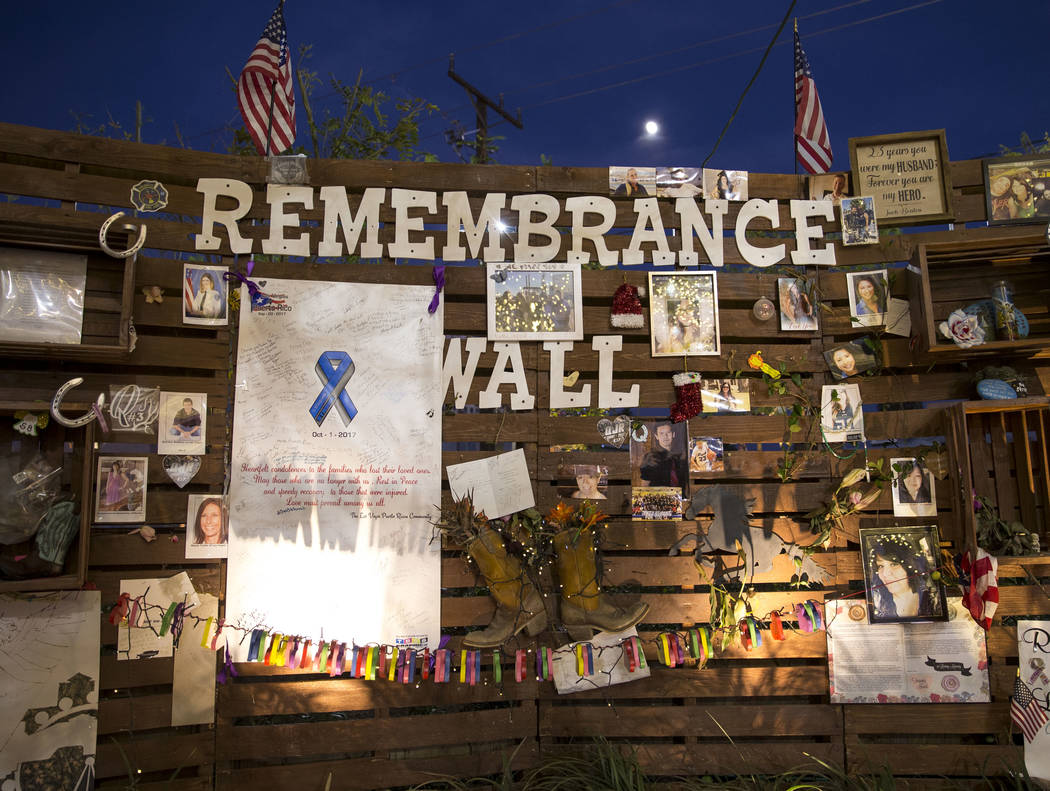

It has been just six months since a sniper on the Strip killed 58 concertgoers and wounded hundreds more on the final night of the Route 91 Harvest festival.

The grief is still fresh. The pain still pulses. And judging by the accounts of at least seven different communities that have each experienced similar mass violence, it is probably too early to start planning a permanent memorial.

“Everybody thinks, ‘You’ve got to do a memorial, do it fast,’” Lora Knowlton, a founding member of the Columbine Memorial Foundation, told the Las Vegas Review-Journal. “Ultimately our advice is: go slow.”

The Columbine High School shooting memorial took about eight years to plan, construct and dedicate. And it didn’t happen without an initial, colossal failure.

That failure took place in a public library near the school, several months after the 1999 shooting, which claimed the lives of 12 students and one teacher.

There, Knowlton and a few others presented the families of the victims with three different design concepts for a possible Columbine memorial, created with the help of a local landscaping firm.

“And they flipped,” Knowlton recalled. “The families were not ready to do a memorial.”

While Knowlton thought she and the original memorial committee were doing the “right thing” on a good timeline, she learned that day that some families “were not getting the time and space they needed to grieve their loss.”

So the committee took a break for about six months, then slowly started back up again.

“But we started back up again with the families in the loop, so they were an active participant in the planning process,” Knowlton said. “I always encourage people to take your time, reach out to the community very methodically, and try to pull together a committee that’s a great cross section of the community itself.”

Here in Las Vegas, the families of about 10 people killed Oct. 1 have already reached out to Clark County Commission Chairman Steve Sisolak, asking about the possibility of a permanent memorial.

“Some family members have told me they’d like something as simple as a flagpole or a tree. Others want something more elaborate,” Sisolak said. “The most important thing to me by far is that we’re really extremely sensitive to the wishes of the families. We need to loop them into the discussions when we move forward.”

Sisolak said at least a year should pass before formal discussions begin about creating a memorial. But it’s an important endeavor to undertake.

“If it would bring some sort of comfort and healing to those families, then I can’t see a downside to it,” he said.

* * *

From start to finish, the planning of the Aurora memorial came with a series of challenges.

There was the obvious grief. And a murder trial, since the gunman lived, which tormented relatives as it dragged on. And, of course, the issue of money.

The entirety of the soon-to-be completed Aurora memorial was funded through private donations. It took years of volunteers working booths at community events — even a lemonade stand — to gather the funds. But by 2016, the group had enough to hire an artist. And by late 2017, the design was approved.

Through the course of many monthly meetings, victims’ families and survivors got to know each other, and, over time, began to heal.

Theresa Hoover, who lost her 18-year-old son, AJ Boik, in the shooting, said the planning process, while slow going, served as a way to “move forward” with her grief and “learn how to work with it to create something.”

In the beginning, one mother said, “none of us could even think or do anything.” But now, there is an overwhelming sense of closure that comes with finishing a proper memorial.

Terry Sullivan, who lost her 27-year-old son, Alex, in the shooting, said she is looking forward to having “a quiet place to come.”

“My son is all over,” Sullivan said. “He shows up in lots of different places. And this will be another place that we can come and feel his presence.”

* * *

The process of establishing permanent memorials has varied across the many communities affected by mass shootings.

Both Aurora and Columbine raised money through private donations that were funneled into a memorial foundation.

In Orlando, where 49 people were killed at Pulse nightclub in 2016, plans are still up in the air, but they are largely being handled by the nightclub’s owner, Barbara Poma.

In San Bernardino, where 14 people were gunned down in 2015, the county is spearheading the planning and the funding of the future memorial, since nearly all of the victims were county employees.

And in Charleston, South Carolina, where nine people were shot dead during an evening Bible study at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church that same year, the memorial-to-be is happening largely thanks to the assistance of a local businessman, John Darby, who offered to help shortly after the tragedy.

“I think, realistically, it’s always good to have a strong partner within the community who steps up and wants to help,” said the Rev. Eric Manning, the church’s current pastor. “Because, technically speaking, the church is not in the business of doing memorials. And this of course is something that we never really had to contend with or had to deal with.”

Virginia Tech’s memorial happened organically, the same day 32 people were killed in the 2007 mass shooting. That night, a group of students hauled 32 hunks of indigenous limestone, “Hokie Stone,” from a nearby construction site to the center of the school’s campus, then arranged them in a semicircle to honor the lives lost.

It was there that future vigils took place in the days and weeks after the shooting. And just months later, the school decided — with input from victim families, survivors, students and faculty — that the makeshift memorial would become the permanent one, once bigger hunks of Hokie Stone, plaques, proper lighting and accessible pathways were installed.

“It just felt right for this community to make what was born that evening the permanent memorial,” Mark Owczarski, the school’s spokesman, told the Review-Journal. “And that memorial is going to be there for as long as this university is here. Because it exemplifies and shows our commitment to remember.”

* * *

In Las Vegas, the county sees itself as the main point of contact for a future memorial, along with the involvement of survivors and victims’ families. That’s because the shooting occurred on the Strip, which falls within the county’s jurisdiction.

Some will want the memorial to focus on the victims, Clark County Assistant Manager Kevin Schiller said. Others will want it to center on the community’s recovery.

“I think the issue is, how do you tie it all together?” Schiller said. “If you have 23,000 people (who attended the festival), how do you categorize the feedback so we can decide what people want to see? We haven’t decided yet how we’re going to do it, but it will have to be strategic.”

Sisolak said a number of location ideas have been proposed for a permanent Las Vegas memorial, including the festival venue, the Clark County Museum and the existing Las Vegas Community Healing Garden, which Las Vegas Mayor Carolyn Goodman said serves as a “living memorial.”

“We are going to continue to develop the Healing Garden,” Goodman said. But for a “memorial of grandeur,” the mayor added, the festival site is “the appropriate place.”

In the meantime, Goodman has forwarded all calls about a permanent memorial to Jim Murren, the CEO of MGM Resorts International, which owns Las Vegas Village, the site of the festival shooting, and operates Mandalay Bay, the hotel that served as the gunman’s vantage point.

MGM Resorts International declined to comment on whether Murren has received any of those calls or taken any action. But in a statement to the Review-Journal, company spokeswoman Debra DeShong said: “The tragedy of October First was heartbreaking for the entire Las Vegas community. Our MGM family still mourns for those lost and those still healing physically and mentally.

“We believe the victims and those who acted heroically to save lives, should be memorialized and honored, and we look forward to working with those affected, first responders and community leaders, to determine the most appropriate path forward.”

* * *

Whatever the site, whatever the plan, however many years it takes, the goal should be to create a place that makes it impossible to forget, Cynthia Nagura said.

Nagura is the director of the Higher Education Center of San Ysidro, California, a satellite college campus that sits on the site of the 1984 McDonald’s mass shooting that left 21 people in the tight-knit border community dead.

The restaurant was razed shortly after the shooting despite pushback from McDonald’s, and the campus was erected there a few years later.

It’s a place that’s full of life, where students can skip a nearly two-hour bus ride to the Southwestern College main campus in Chula Vista and instead attend class close to home. On a recent day, students filed in and out of the front doors with backpacks and textbooks, shouting out at friends to go over notes or catch rides.

“We look at it as a way of turning a tragedy into a triumph,” Nagura said of the campus being created at the shooting site.

At the front of the small building, a modest memorial still recognizes the children and adults killed there more than 30 years ago. Students decorate it twice each year — on the July 18 anniversary and on Day of the Dead, Nagura said.

“That day, people died too young. They died tragically. They died violently. And it shouldn’t have happened. But not only can we not forget it, because violent acts have got to stop, but those are people that deserve to be remembered,” Nagura said. “As long as the memorial has been there, people walk by and they stop. And they look. And they read.”

Contact Rachel Crosby at 702-477-3801 or rcrosby@reviewjournal.com. Follow @rachelacrosby. Review-Journal staff writers Jamie Munks, Michael Scott Davidson and Todd Prince contributed to this report.