Ellsworth Kelly’s deceptively simple works on display at Barrick Museum

Just because it looks easy doesn’t make it so.

Consider the works of renowned abstract artist Ellsworth Kelly, who died at 92 late last December in his native New York state.

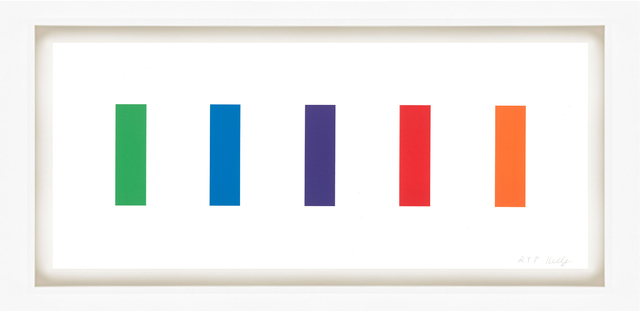

Peruse the Kelly lithographs now on display at UNLV’s Marjorie Barrick Museum and you may find yourself taken aback by their seeming simplicity.

Their very titles — “Color Panels,” “Green Curve,” multiple prints named for a single color, from “Dark Purple” to “Red” — suggest Kelly’s minimalist approach.

Better still, compare two prints with the identical descriptive title “Red.”

The 2001 “Red,” with its bent angle, resembles a bright scarlet elbow or knee brace.

As for 2003’s mostly rectangular “Red,” with its darker crimson hue and gently arched top, it might be a garden gate glimpsed from an off-kilter angle.

“Black Curve” and “Red Curve,” both from 1999, could depict buildings meeting sidewalks, again from an oblique perspective. Or they might be descending guillotines. (Or simplified outlines of the Nevada map.)

Simple, yes, but not easy — as Barrick guests have found during the museum’s visitor-made art activities, which take place from 4 to 7 p.m. the third Thursday of the month.

As one visitor who participated in a recent “Color Compositions” session told museum director Aurore Giguet, “ ‘Making these simple shapes is not so easy.’ ”

Kelly’s prints, arrayed in the museum’s Inner Gallery, attest to the artist’s mastery of color and geometry.

Kelly “was a true original,” according to his New York Times obituary, “forging his art equally from the observational exactitude he gained as a youthful bird-watching enthusiast; from skills he developed as a designer of camouflage patterns while in the Army; and from exercise in automatic drawing he picked up from European surrealism.”

Beyond the subtle curves and saturated color of some prints, Kelly’s drawings reveal sharp, precise lines, whether it’s the fluttering leaf pennants of 1992’s “Oak VII” or the ruffled trumpet of 2004’s “Daffodil.”

And when the artist deals with faces — his own, in a varicolored strip titled “EK Spectrum II” (1988) or that of his husband, Jack Shear, in 1988’s “Jack I,” Jack II,” “Jack III” and “Jack Gray” — the features emerge as a collection of shapes that coalesce to form eyes and smiles.

Organized by Las Vegas-based art consultant Michele C. Quinn of MCQ Fine Art Advisory, the Kelly exhibit came about when Quinn and Giguet “were in the middle of a conversation” regarding future exhibits, Giguet recalls, “and Ellsworth died.”

The resulting display of lithographs by an artist of Kelly’s renown “is starting us on a new upward momentum,” Giguet adds. “We’re getting a lot of great feedback — and a lot of new visitors.” (Those new visitors can see the work of other eminent artists, from Robert Motherwell to Frank Stella, in the Barrick’s adjacent “Unseen Selections From the Las Vegas Art Museum Collection” exhibit.)

To help visitors understand Kelly’s artistic process, free showings of “Ellsworth Kelly: Fragments” continue at 1 p.m. Saturdays through May 14, the exhibit’s final day. The 2007 documentary follows the artist revisiting the Paris of his early 20s, exploring early influences that would become motifs he returned to, refined and reworked throughout his career.

And at 6 p.m. Wednesday, museum visitors will hear firsthand about “Printmaking With Ellsworth” in a conversation with artist Erik Beehn, who worked with Kelly as a master printer at Gemini Graphic Editions Limited, a Los Angeles-based fine art publisher.

Kelly “had a longstanding relationship” with Gemini and “had an open invitation” there, Beehn notes in a telephone interview from his Chicago home.

During Beehn’s years at Gemini (2005-2010), Kelly often would send Beehn “color, curves, the sort of shapes” he was working on, then would come to Gemini to supervise the proofing of a print, a process that took from “four days to two weeks.”

Over time, “the goal was to build a relationship with the artist,” Beehn adds. “There’s this buildup to understand their voice, know their characteristics and thought process” to “become an extension of their voice.”

The goal: to “understand what this person would want, so you could maintain their integrity.”

Through working with Kelly, Beehn found him “to be fairly quiet,” but “real attentive to very, very small details.”

Kelly “really understood what (abstraction) meant,” knowing “what needed to be removed and what needed to remain,” Beehn says. “Taking taste out of it, by pulling from the things that are” familiar, Kelly was “taking us somewhere that’s maybe not so familiar.”

Read more from Carol Cling at reviewjournal.com. Contact her at ccling@reviewjournal.com and follow @CarolSCling on Twitter.

Preview

"Ellsworth Kelly"

9 a.m.-5 p.m. weekdays (until 8 p.m. Thursdays), noon-5 p.m. Saturdays, through May 14

Marjorie Barrick Museum, UNLV, 4505 S. Maryland Parkway

Free; suggested donation $2-$5 (702-895-3381, unlv.edu/barrickmuseum)