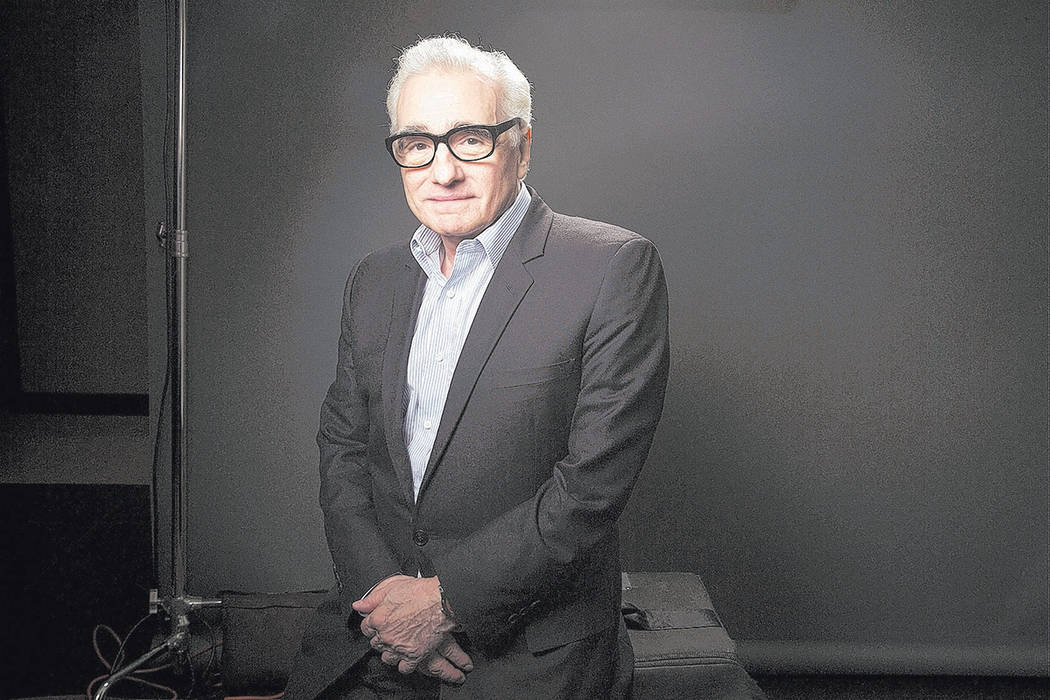

Martin Scorsese on appeal of wise guys, new film ‘The Irishman’

Martin Scorsese will never say, “It’s a wrap.” At age 77, he’s old enough to retire, but the screen legend said there will be plenty of action — mob and otherwise — in his future. “Retire from making movies?” said one of the greatest filmmakers of all time. “You’ll have to stop me yourself. You’ll have to tackle me to stop me.”

No one is lining up for that job. No one has time. They’ll be in front of their big screen starting on Nov. 27, when Scorsese’s “The Irishman” comes to Netflix. Based on the book, “I Heard You Paint Houses” by Charles Brandt, the film tells the saga of World War II veteran and truck driver Frank Sheeran (Robert De Niro) who is introduced in a nursing home in his wheelchair. He’s a hustler and mafia hit man involved with one of the greatest unsolved mysteries in American history — the disappearance of union boss Jimmy Hoffa (Al Pacino). The street drama also stars Scorsese staples Joe Pesci and Harvey Keitel.

The director of screen classics including “Taxi Driver,” “Raging Bull,” “Goodfellas” and the ultimate Vegas movie, “Casino,” is heading into awards season strong with buzz of best picture, best director Oscars and a slew of potential acting nominations.

Review-Journal: What is your idea of a great Sunday?

Martin Scorsese: I’m watching movies, of course. Give me some great old movies and a good meal with family and friends.

“The Irishman” is a story of corruption. Why does that topic fascinate you so much?

Corruption is part of a human being. It’s always there. The dark forces are always there. The question is: Do we succumb to them? The answer: All the time.

Robert De Niro handed you this book. Were the two of you actively looking to work together again?

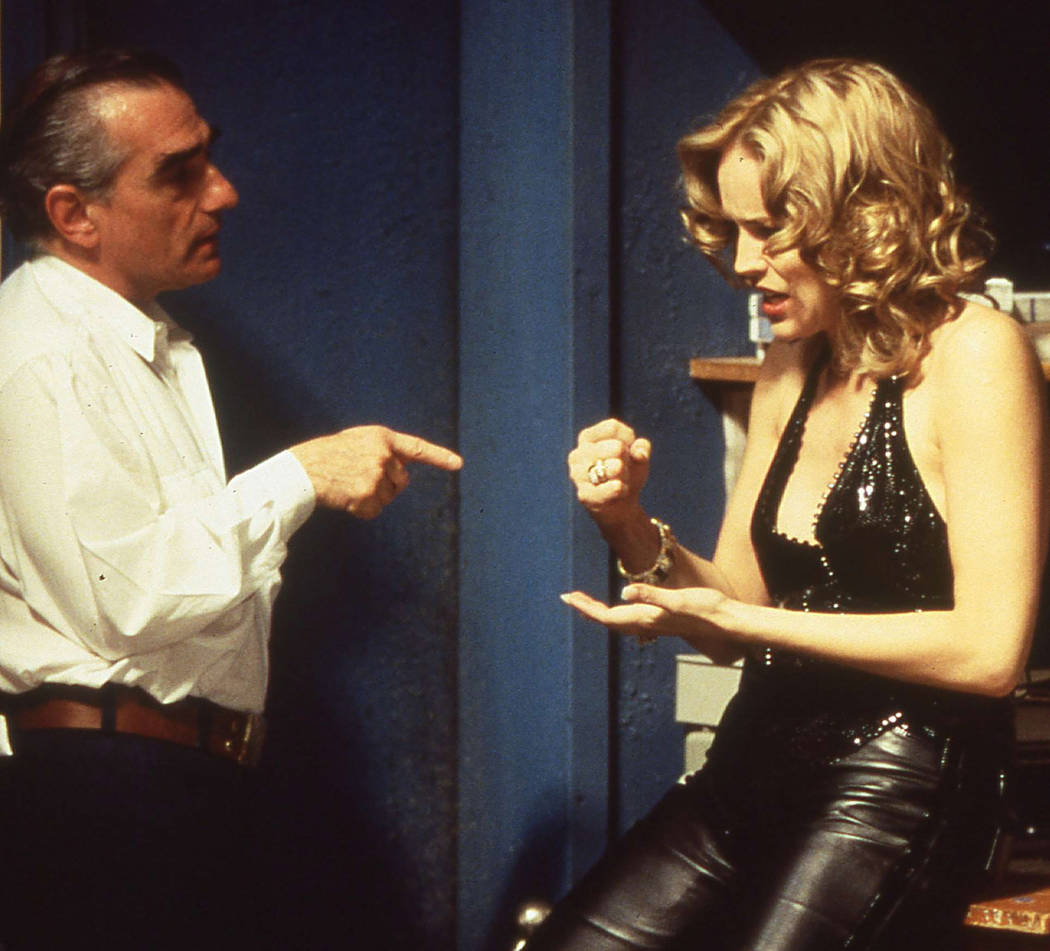

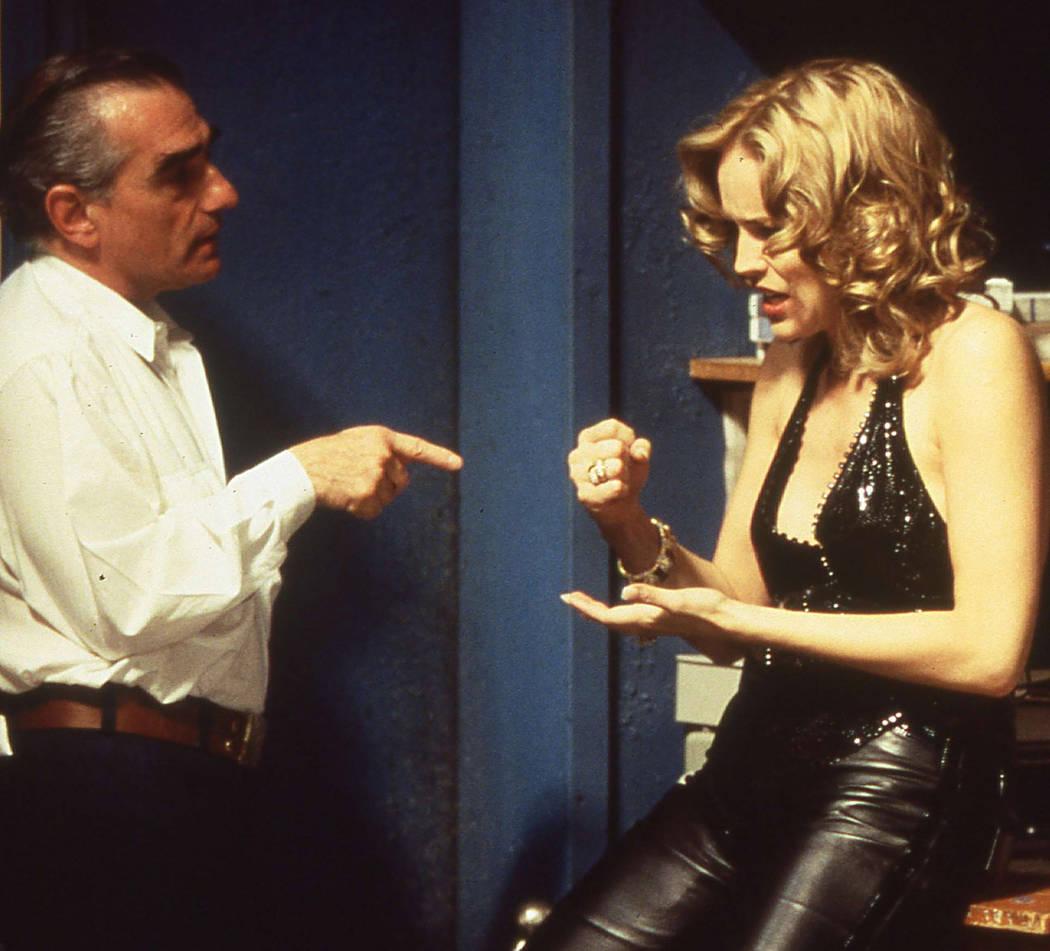

Bob and I wanted to work together since we did “Casino” in 1995, but we had never quite connected. We were actually about to do something else when Bob said, “Marty, you gotta look at this. See what you think.” I could see that Bob was very strongly attached to the character of Frank. I read the book. Actually, we didn’t have to say much. We just knew.

But then it took 10 years.

We just couldn’t get the backing for years. Before that, things got in the way. I don’t mean negatively. There were issues and obligations and we had to wait for the technical to catch up.

It’s amazing how you get Pacino and De Niro to look decades younger in the film.

That was thanks to Industrial Light & Magic and visual effects supervisor Pablo Helman. I didn’t want to interfere with the actors talking with each other.

Pacino told a funny story that despite looking younger, he still had the walk of a 79-year-old guy until you both worked on changing it.

It was the first day I ever worked with Pacino and I said after a take where he had to appear 49, “It’s good, Al. We’ll maybe do one more. Remember you’re 49. Get out of the chair at that age.” We did the next take and Al said, “What did you think?” I had to say, “Okay, now you’re getting out of the chair at age 62, but we still gotta get down to age 49.” And the next take, he did it.

When did you first meet Pacino?

I first met Al in 1970, when he was directing this play called “Rats.” Francis Ford Coppola introduced us. Al and I always said that we wanted to work together, but over the years, it just went differently. A few projects didn’t come to fruition. Then, I remember meeting with Al about six years ago in Beverly Hills about “The Irishman.” Al said, “Is this movie going to happen before we get any older?” I promised him, “Yes, it will.”

You credit asthma for your early love of movies.

I grew up in New York on Elizabeth Street. I saw everything from my bedroom window on the third floor because of asthma. I couldn’t run around like the other kids, so I’d sit in my room and look out the window. I’d imagine the stories going on below.

Is this where you got your early love of gangster stories?

My house was bounded from the East at that time by what they called Devil’s Mile bowery. On the West, it was called Murder Mile. Those were names given to those places over decades. They had to have elements of the dark side. That’s where I grew up, and it fascinated me.

Is it true that your father actually coined the term “goodfellas?”

Yeah, my father and (screenwriter) Nick Pileggi were talking. It was a mumbling, coded language. It was like, “Yeah, he’s okay He’s all right. He’s a good fella.” It sounded better than just saying, “He’s a wiseguy.”

What is one of your favorite memories of making “Raging Bull” with De Niro in 1980?

One day, we were at this gym on 14th Street in New York. Bob got in the ring with a big guy named Jimmy. I was just recuperating from a long period that was a desperate search as to what kind of film to make now. I just sat there at the gym and realized that you can’t just shoot a boxing scene. You have to design it all. Like choreography. For a moment, I just froze while they continued to fight. I was figuring it all out. Finally, Bob said to me, “Are you OK? And, by the way, I’m killing myself out here. Are you paying attention?”

“Casino” is the quintessential Vegas story.

We had these conversations that were almost philosophical on the set of “Casino.” We’d say, “God gave those characters this paradise of sin. He gave them Vegas. And they still screwed it up and got cast out of paradise.” We used to sit around and talk about what that meant.

What does it mean?

That movie still reminds me of the story Nick used to tell us about a guy in the old neighborhood who was a thief. He would go to church a lot and pray to God to give him the strength to steal some more. He would say, “Please God. I have to work. It’s all I know!” The way those guys were in “Casino” … it was all they knew.

Why do audiences love the depraved characters the most?

I think everyone likes to explore the darker side of human nature in a film because then you don’t have to live it in real life.