Photographer Robert Knight has shot rock ‘n’ roll icons

Robert M. Knight is no musician, despite having worked with some of rock ‘n’ roll’s best over the past 50 years. But what Knight lacks in skill on the guitar — his favorite instrument — he more than makes up for with his camera.

That, he plays like a virtuoso.

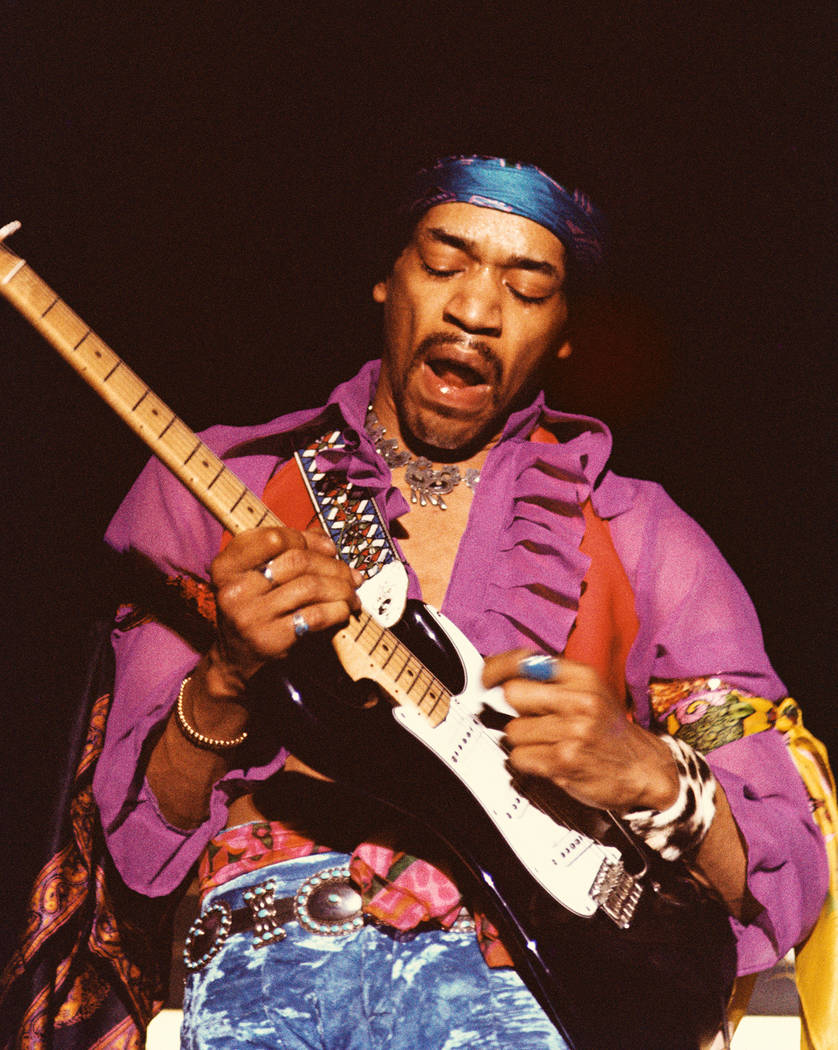

You have probably seen Knight’s photographic artistry, even if you didn’t realize it. Many of his photos of Led Zeppelin, Jimi Hendrix and other rock pioneers have become iconic, in part because Knight took them early in the artists’ careers, before they became icons.

Some choice portraits from those days can be seen in “Rock Gods: Fifty Years of Rock Photography” ($19.99, Insight Editions, to be released Tuesday). Knight says those photos represent an era in rock photography that’s very different from today.

“When I shot (Jimi) Hendrix, I shot one roll of film. One roll. Fourteen shots, and all 14 got used eventually,” he says. “It was an art. It was a craft. Photography was almost alchemy back in the day. We had to process our own film, we made our own prints. Today, nobody knows what that is. They don’t know a darkroom. Photography, to me, is all of that.”

An early passion

Knight, 69, was born in Los Angeles and grew up in Hawaii. He and his wife, photographer Maryanne Bilham, moved to Las Vegas in 2005. As a teenager, Knight found some British music magazines that a tourist had left behind and, intrigued, ordered from England a few records he saw in the ads.

The Yardbirds. The Who. The Pretty Things. “I had them even before they came out in the U.S.,” Knight says.

When The Rolling Stones played Hawaii, “I went and was absolutely electrified, because these kids were screaming and flashbulbs were going off and I had goosebumps. That just did it for me. I just said, ‘I have to go to England. I have to figure out how to get there.’ ”

Through his job at a travel agency, Knight scored a ticket to England and spent the summer of ’66 in swinging London. He was entranced.

“I was like, whatever this is, I want to be a part of it,” Knight says. “But how, because I didn’t play music?”

The film “Blow-Up,” about a London photographer, “triggered in my head that I could be a photographer,” Knight says. “I knew if I did that, I could have access to these bands.”

Using earnings from his golf course caddying job, Knight bought a Nikon camera and a few lenses and began doing travel photography for airlines, hotels and cruise lines. “That enabled me to have sufficient money to chase the bands,” Knight says.

Aiding the next generation

In 1968, Knight moved to San Francisco, ostensibly to attend college but really to pursue music photography with such publications as Rolling Stone.

“The first concert I ever shot as a rock photographer was Jeff Beck and his first solo tour with Rod Stewart and Ronnie Wood,” Knight says. The next day, when Knight went to show the photos to Beck, Beck told him about a band Jimmy Page was putting together.

“I found out they were going to come to America right at the beginning of the new year, and in (January) 1969, I convinced (Rolling Stone founder Jann) Wenner to write me a letter so I could shoot them at the Whisky a Go Go in L.A.” Knight says.

Even then, Knight knew Led Zeppelin would be big. Throughout his career, Knight gained a reputation for being able to spot up-and-coming guitarists, a gift that was the focus of “Rock Prophecies,” a 2009 documentary about him.

Knight’s passion for the guitar and guitarists also lies at the heart of a program Knight created called “Brotherhood of the Guitar,” a mentoring program that currently includes more than 130 promising musicians from around the world.

Knight suspects that one reason he’s been able to bond so well with musicians is that he’s not a musician himself. The first time I got invited to come to Jeff Beck’s house and stay a week or so, he said to me, ‘You play guitar?’ No. ‘Are you interested in playing guitar?’ No. He went, ‘Good. I think we might have a good time.’ ”

Another reason: “I knew when to not take out the camera,” Knight says. “I’d go to Jimi Hendrix’s house, and they’re in swimsuits and I’d never take a picture. People say, ‘That’s weird. Why didn’t you shoot?’ I wasn’t trying to take advantage of the artists, you know?”

Music and travel

Knight still does music photography, including hundreds of 10-foot-tall portraits that he and his wife have created for display at more than 250 Guitar Center stores nationwide.

Knight also continues to do travel photography, which he calls his “hidden career.”

“What a lot of people don’t realize is that, for the same amount of time, going on 50 years, I was one of the higher-paid travel photographers, working for airlines and hotels and cruise ships in 110 countries. I’ve created a massive travel archive I have to this day, and I’m working now on my travel book, which is going to be quite esoteric.”

“I’m an explorer, really,” Knight says. “I love photographing all the strange places on Earth.”

So not that different from photographing rock stars ? Knight smiles.

“I’ve collected guitar players,” he says. “And I collect weird places.”

A last conversation with Stevie Ray Vaughan

One of Robert Knight’s most vivid memories came in 1990, when he went to Alpine Valley Resort in Elkhorn, Wisconsin, to photograph a roster of guitarists including Eric Clapton, Stevie Ray Vaughan, Buddy Guy and Robert Cray.

“Amazing,” he says. “But I had some very strange, heavy conversation with Stevie Ray Vaughan, who told me he knew he was going to die. We got into talking about all of this, and Stevie says, ‘If anything ever happens to me, you’ll know me when you hear me.’ “

“He did this incredible concert,” Knight says. Then, as Vaughan was leaving the venue after the show, the helicopter in which he was riding crashed shortly after takeoff, killing Vaughan, 35, and four others.

Knight had taken Vaughan’s final photos.

“The next day, my phone rang off the hook. Everybody found out I was the only photographer,” he says. “And I didn’t let anybody have them.

“They said, ‘Can you imagine what this will do for your career?’ I go, ‘I’ve had a career. You guys didn’t call me before.’ What was I worried about?”

Contact John Przybys at reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0280. Follow @JJPrzybys on Twitter.