Annual Vegas Valley Book Festival returns for print fanatics

Print is dead? Readers have just up and disappeared?

If so, that’ll be some crowd of enthusiastic mourners and MIA bibliophiles crowding the 12th annual Vegas Valley Book Festival, which runs Wednesday through Saturday.

As always, the festival will feature talks, panels and programs featuring dozens of authors, illustrators, artists, storytellers, essayists and practitioners of just about every permutation of the printed or spoken word.

The festival’s keynote speakers will be Catherine Coulter, who forged an immensely successful career in the historical romance genre before adding thrillers to her literary resume, and Luis Alberto Urrea, whose work ranges from Pulitzer prize-nominated nonfiction to fictional-but-fact-based explorations of personal and Mexican mythology.

Coulter will speak at 7 p.m. Wednesday at the Clark County Library, 1401 E. Flamingo Road, while Urrea will speak at 5 p.m. Nov. 2 at the Historic Fifth Street School, 401 S. Fourth St.

For more information, visit VegasValleyBookFestival.org.

LUIS ALBERTO URREA

Borders. They divide us. They separate us. They keep us from learning about one another.

Luis Alberto Urrea knows about borders. He grew up, at various times, on one side or the other of the U.S.-Mexican border. In his books, he has explored both the physical reality of the border and, on a more intangible level, the borders that separate cultures and, even, the physical world from what might lie beyond.

During a recent phone interview, Urrea agrees that the tangible and metaphorical notion of “the border” has been a theme of his work.

“People are always like, ‘Wow, you’re so interested in human rights and Mexico and the border,’ and I always tell them, ‘No, I’m telling them about the border that divides human beings,’ ” he says. “I think that happens to be a handy metaphor, because that’s where I’m from.”

Urrea was born, as he puts it, “a child of poverty” in Tijuana, Mexico to a Mexican dad and an American mom.

“I’m exactly half and half,” he says. “I was raised by each of them to be 100 percent of what they were — my dad raised me to be Mexican and my mom raised me to be American. So I felt I had two upbringings at once.”

Urrea experienced the effects of that dual upbringing throughout his youth, even — maybe especially — after moving to the United States. And while he read a lot as a kid, he doesn’t recall being particularly enamored of the notion of becoming an author.

“I’ll be honest with you,” he says with a laugh. “I wanted to be in Led Zeppelin. I wanted (Robert) Plant’s hair and I wanted my own jet, the ‘Urrea Starliner,’ and somehow I thought writing poems about girls was going to get me the Urrea Starliner.

“Really, I was a music freak. I was the kid who lived in Leonard Cohen and John Lennon and Jim Morrison and Bob Dylan. I wanted to do that so badly.”

He recalls once stumbling across a book of Morrison’s poetry. “I thought: ‘Wait a minute. Morrison writes?’ So when I was going to junior high and high school, especially, my buddies were all guitarists, so I became the mystery lyricist. It was sort of to fake my way into rock ’n’ roll.”

He later pursued a drama major and had a small theater troupe with some friends. He was a cartoonist. Eventually, he discovered literary voices closer to his own than he might have thought. It wasn’t until college that he knew a single Latin American author. “It was all Longfellow and John Greenleaf Whittier.”

Then, Urrea saw not only Mexican and Latin American authors and poets, but authors and poets from Japan and China and Russia and Poland and Africa, too.

“I was like, what is this world?” he says.

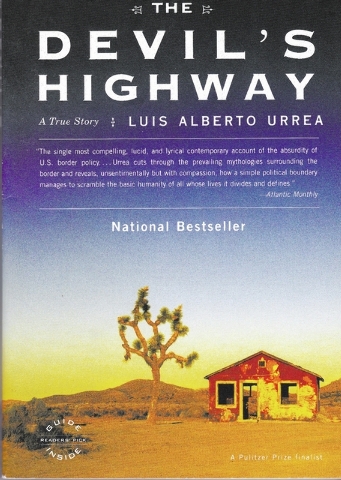

Eventually, Urrea would add to that universe of globe-spanning authors with his own work. His first book, “Across the Wire,” included personal stories of his own time, in his 20s, working with missionaries at Tijuana’s municipal garbage dump. There was a memoir, “Nobody’s Son: Notes from an American Life,” and “The Devil’s Highway,” a Pulitzer Prize finalist for nonfiction, about an ill-fated border crossing by more than two dozen Mexican immigrants in which the Arizona desert becomes a character all its own.

He drew upon Mexican and family mythology for “The Hummingbird’s Daughter” and its sequel, “Queen of America,” historical novels that told the amazing true story of one of Urrea’s great-aunts.

He had grown up hearing stories about Teresa Urrea, who was renowned as a healer, clairvoyant and advocate for Mexico’s poor and who some consider Mexico’s Joan of Arc. Her life would make even the soapiest telenovela look downright pedestrian.

“People in my family were exaggerators and storytellers and inveterate liars, and they’d make up stuff all day and night about the devil and ghosts and walking skeletons,” he says. “And, in the midst of this, they start telling me about this aunt: ‘You’ve got a Yaqui Indian aunt’ — I thought that was cool — ‘and she can heal the sick and raise the dead’ After a while, it’s, ‘She could fly!’ So you start getting a little suspicious.”

Urrea stopped thinking about it much until his first teaching job in San Diego, when a professor told him, “You’re related to the saint … Saint Teresita.”

Urrea decided to look into it and ended up doing about 20 years of research before telling his great-aunt’s story.

Why craft her real-life story as fiction? “Sort of my wise guy answer, which isn’t really wise guy but sounds like it, is: It was always going to be a nonfiction book, but I realized you can’t footnote a dream,” Urrea says.

Urrea recalls one editor who loved “The Hummingbird’s Daughter” but returned it dripping in red ink.

“It looked like ‘The Texas Chainsaw Massacre,’ and I’m looking at it, and every miracle was cut out and every weirdness was cut out,” he says. “I called him and said, ‘What did you do?’ He said, ‘It’s a historical novel.’ I said, ‘Yes.’ He said, ‘I’m cutting out all the woo-woo stuff.’ I said, ‘The woo-woo stuff is the history.”

It’s probably not surprising that Urrea’s work so far has delved so deeply into cultural mythology.

“I think what happens is you internalize a place until it becomes a kind of mythology inside yourself, then you start creating out of that,” he explains. “I’ve been really lucky in that I’ve gotten to know a whole lot of places and cultures and stuff that I never thought I would have.”

“Writing about where I’m from is a sort of bearing witness.”

While Urrea’s work so far has revolved heavily around the heritage of his father, he’s working on a book that will explore the heritage of his mother, who served as a Red Cross worker during World War II. He’s scouring historical sources and self-published memoirs of Red Cross workers to tell their stories. Think of it, he suggests, as a sort of “Band of Sisters.”

“This is blowing my mind,” he says. “This one is just amazing to do. My mom was one of those invisible ladies nobody paid attention to, and you realize they aren’t at all invisible. … I mention it to audiences and people flip out.”

Of course, Urrea adds with a laugh, longtime readers “are going to go through the book, like, “Where’s the Mexicans, man?’ But it’s a story that matters to me.”

CATHERINE COULTER

Catherine Coulter is a best-selling author of more than 70 books. After making her mark in the historical romance genre, she branched out into thrillers.

Via an email interview, Coulter notes she is editing “Power Play,” the 18th entry in her FBI thriller series, which is scheduled for release next summer. “The Final Cut,” the first book in her internationally set “A Brit in the FBI” series (written with J.T. Ellison) was released last month.

“It’s all great fun and will mean not one, but two FBI books a year,” she writes.

Coulter ended up jumping into a new genre after writing three trilogies of historical romances over the course of 4½ years.

“Oodles of words,” she says. “I was burned to my heels.”

She was ready for a change. “I was at a family reunion in Texas when my sister walked up to me and said, without preamble, ‘Have you ever heard of a little town on the coast of Oregon called The Cove? They make the world’s greatest ice cream and bad stuff happens,’ ” Coulter says. “I went en pointe.”

“The Cove” became the first book in her FBI series.

“I very much like going back and forth between thrillers and historicals because the genres are so very disparate,” she says. “It keeps the brain unconstipated.”

Romance, where Coulter first made her mark, has subdivided itself into subgenres that cover everything from Amish to paranormal romances. Coulter says she’s fine with that.

“I have to say the mystery genre could use all of those subgenres to good effect as well,” she writes.

“The fact is though, the romance genre and all its delightful subgenres is by far the most popular in the world. Well over 60 percent of all paperbacks/ebooks sold are in the romance genre.”

It makes sense, Coulter says, “because romance is all about relationships, so what’s not to like? It crosses all borders, all genres, all cultures.”

The advent of self-publishing also has allowed writers of every genre, including — perhaps, particularly — romances to directly reach a marketplace of avid readers. Coulter considers self-publishing a wonderful development in the ever-evolving publishing industry.

“No more having to depend on the whims of a traditional publisher or an agent. No, all the power can now be in the writers’ own hands. Sink or swim, the opportunity to get your work out to the public can now happen without anyone’s approval or interference. I’m all for it.”

And how about her own literary influences?

“I’d have to say Georgette Heyer was my biggest influence since my first six books were Regency romances,” Coulter replies. “The old adage of ‘write what you love’ to read is certainly true in my case.”

Contact reporter John Przybys at jprzybys@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0280.