Clark County training for school assailant stresses hiding over fighting

It should be muscle memory.

When a lockdown is called in a Clark County school — whether it’s a drill or a real “active assailant situation” — teachers are expected to quickly hustle students out of hallways and into classrooms, lock the doors and turn off lights and get everyone into a hidden position.

From that point, there’s a lot of waiting.

Clark County teachers and students practice the process at least five times a year in state-mandated lockdown drills.

That used to be where the discussion of training for the unthinkable ended.

But school shootings like the one last month in Parkland, Florida, which killed 17 people, have school officials nationwide reevaluating safety. That means looking at and discussing possible quick fixes — things like requiring students to carry transparent backpacks or establishing single points of entry to campuses — as well as costly solutions — like hiring more police officers and increasing mental health services.

It also means looking at how schools prepare students and teachers and whether that instruction should instruct them to engage with an assailant if necessary.

Training to engage

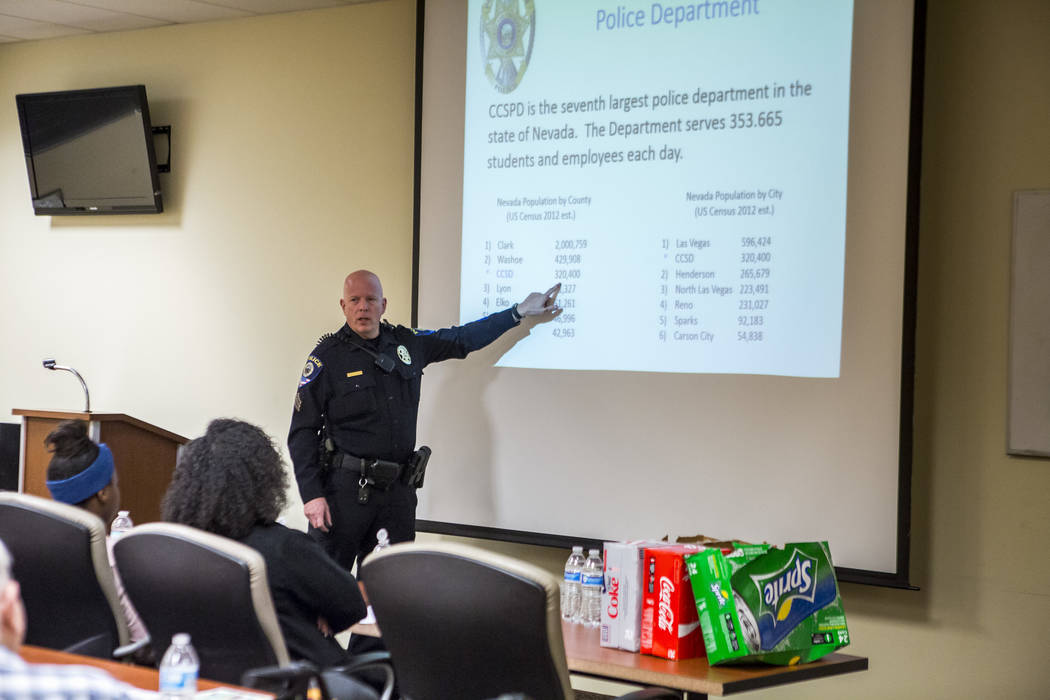

Clark County’s policy is primarily one of avoidance, but there are different schools of thought.

Companies like the ALICE Training Institute provide instruction that prepares teachers to fight back against assailants in certain situations. And in 2012, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security unveiled a video for a program called “Run. Hide. Fight.” that calls for different strategies depending on the nature of the threat.

Greg Crane, founder of ALICE, started his company 17 years ago after a dinner-table discussion with his wife, a school principal in Texas.

His trainings seek to answer questions most people don’t even want to think about: What do you do if the assailant breaks in through the locked door?

“For far too long, too many people at schools were taught to sit in a corner of under a table. That’s fine if the bad guy never makes contact with you,” he said.

The training ALICE provides is about taking back control of the environment, Crane said. One way to accomplish that is to create “sensory overload” for the assailant. They train teachers to scream, shout, throw things, move around, anything to distract the assailant.

Crane also encourages teachers to knock out windows to evacuate schoolkids in certain circumstances. He cited a case from January 2017 at West Liberty High School in Ohio, where students and teachers in classroom broke windows with chairs and other objects and escaped when a student with a shotgun shot and wounded a classmate.

The toll could have been far worse if teachers weren’t trained and empowered to take that action, he said.

More than 4,100 school districts across the country work with Crane’s company.

While the Clark County School District’s official policy stresses hunkering down, Michael Wilson, the district’s director of emergency management, said teachers and staff have some leeway to deal with an assailant.

Individual initiative encouraged

“We want everyone to individually take action with what they see with the situation,” he said. “What I feel comfortable doing would be very different than a staff member next door.”

One part of the ALICE training that CCSD is wary of, Wilson said, is its emphasis on communicating in the midst of a crisis such as an active shooter incident. Wilson said that would be fraught with danger.

If, for example, there’s someone in the 300 hall and that gets called in to the front office, then officials might advise staff in the 400 hallway that it’s safe to evacuate. But what happens if the assailant has moved into the 400 hallway in the interim? That’s the worry, Wilson said.

The district, and Crane, also have concerns about the Department of Homeland Security’s “Run. Hide. Fight.” approach, saying the difficulties of training teachers, staff and students when to employ which strategy would outweigh any security gains.

“It’s a tough decision at that point. We can’t train children they have to fight,” said school district Police Chief James Ketsaa.

Some psychologists also warn that training that closely mimics reality can cause harm or trauma.

“We don’t light a fire in the hallway to practice fire drills,” said Melissa Reeves, an associate professor at Winthrop University in South Carolina and former president of the National Association of School Psychologists.

Lockdowns should remain the cornerstone of training, as they’ve proven to be effective deterrents against assailants, said Reeves, who also advocates for more mental health awareness and treatment in schools. She agreed that any training needs to address contingencies such as an assailant getting past a locked door, but said that training needs to be done carefully.

Other discussions

Training isn’t the only area officials want to look at in the aftermath of events like this. Schools officials are looking at ways to make schools physically safer by limiting access points and other measures and searching for funding to get more adults on campus to be on the lookout for both internal and external threats.

That might be a combination of more police officers, more school psychologists or teachers, all of whom experts say can help avert violence from within by identifying troubled students and providing support.

Spokeswoman Kirsten Searer said the district is looking bring proposals to the Legislature next year.

“We just need more adults on campus to form relationships with students and hopefully be able to support them before it gets to this point,” Searer said. “We’re having a conversation with trustees and our employees and students and parents about what we want to bring to the Legislature in 2019.”

Some principals aren’t waiting.

Principal David Wilson set up a folding table at the front entrance to Eldorado High School last month. Now whenever the east Las Vegas school is in session, someone is stationed there to act as a lookout for any potential assailant who may want to cause harm to his students.

“You’re greeted in a nice, friendly fashion, but you’re also looked at and directed to where you need to go,” he said.

Contact Meghin Delaney at 702-383-0281 or mdelaney@reviewjournal.com. Follow @MeghinDelaney on Twitter.

Dueling safety summits

Gov. Brian Sandoval on Friday announced that a meeting State Superintendent of Instruction Steve Canavero and all the local superintendents to start a statewide discussion on school safety will be held on Monday.

Sandoval initially announced the summit after a National Governors Association meeting in late February.

"The discussion with the superintendents will be the beginning of a dialogue and could lead to an executive order designating a commission on school safety that will expand this initial conversation and include students, teachers, parents, faculty and others who have the shared goal of prioritizing campus safety. This citizen group will eventually provide recommendations on possible action from the executive branch and inform the 2019 Legislature," he said in a statement.

Attorney General Adam Laxalt is planning his own school safety summit on Wednesday.

"As the state's chief law enforcement officer, I am uniquely situated to lead a statewide discussion regarding school safety with law enforcement officials, teachers, school administrators and security experts," said Laxalt, who is seeking the Republican nomination for governor. "Our priority is to identify and discuss procedures for responding to violent threats and making our Silver State a safer place for families."