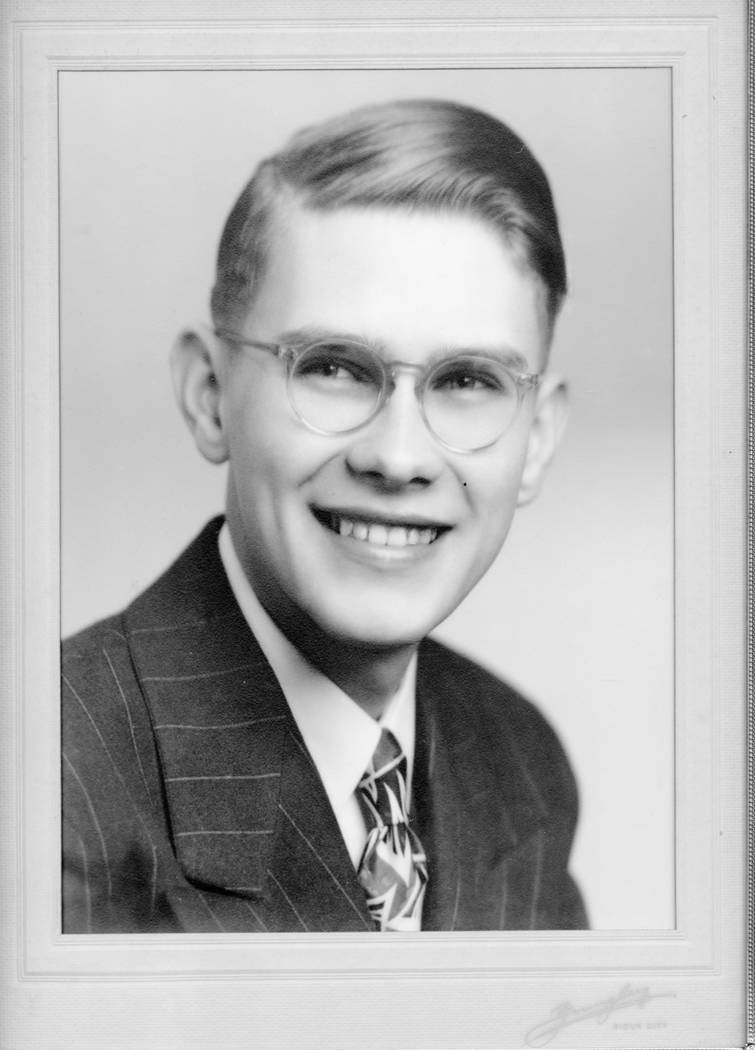

Arthur Nelson, known as Las Vegas’ ‘Chip Monk,’ dies at 86

A young Arthur Nelson went to church with his parents every weekend in Iowa. There, he squirmed in the pews. The sound of the organ kept him awake. As the music echoed, the only child picked up a book of hymns.

He started to see what the songs looked like written down. And little by little, he fell in love with the sounds of the organ, friends recalled him telling them. The four keyboards that acted like a drum. The only instrument that requires special organ shoes.

Before the longtime Las Vegas resident died of natural causes on Aug. 19, Nelson picked out the church for his memorial service: Christ Church Episcopal. The church has a pipe organ — the biggest, most expensive organ in the city of Las Vegas. He worshipped there for 50 years and had donated funds to buy the organ.

Nelson, 86, served as an organist at the Guardian Angel Cathedral on the Strip for more than 30 years. In 1959, he moved to Las Vegas to work for the Review-Journal, where he operated the linotype machine, a “line-casting machine” used in the printing process. He called it his “dream job.”

Nelson, born Jan. 22, 1931, had brown hair in his younger days and big, round glasses. He was always well-dressed and well-groomed with a big smile on his face, friends remembered.

Nelson was known to many as the “Chip Monk” since at least the late 1980s for taking on the responsibility of redeeming casino chips dropped in collection plates during Mass, said Betsy Ann Fiore, who worked with Nelson at the church as a cantor.

Fiore and Nelson met in 1996. She was a 37-year-old California lawyer who recently had relocated to Las Vegas. But her real passion was singing. She had an opera voice, big and loud.

“Do you need any singers?” She asked Nelson one day at the Guardian Angel Cathedral.

“Well, let me hear you sing,” Nelson said.

From then on, she worked every weekend for more than 21 years. “Because of Arthur,” she said. He taught her the songs. He trained her. He brought out the best in her, she said.

Jokester and friend

Nelson didn’t have family in Las Vegas, never married or had children of his own, but he was close to those special to him.

Nelson’s friends said he would stop at nothing for someone he cared about. He never bragged about himself. Instead, he tooted the horns of others and the good things they did. Meanwhile, his friends boasted about him.

He also had a lighter side, friends said.

He loved to try to make women blush with off-color jokes, said Timothy Cooper, a musical director at First Christian Church, who first met Nelson 37 years ago. Despite being a jokester, he said, Nelson was most alive in church.

“He was sensitive to the subtleties of liturgy and hymnody,” Cooper said.

But Fiore remembers his jokes more. At the start of service, she was nervous to sing her solos.

“Betsy Ann,” Nelson would say, before delivering a long speech. At the end, he would crack a joke.

“What’s the difference between outlaws and in-laws?” he said one day, snickering. “Outlaws are wanted.”

Fiore, now 59, visited Nelson a few days a week. Six months ago, he asked her to write a different tune to sing at his memorial, she said. The song was “A Perfect Day” by Carrie Jacobs-Bond.

“Do you want me to write it with somebody else?” Fiore asked.

“No. You. I want you to write it,” he told her.

Nelson lived on memories. As a boy during World War II, his mother took him out to Oregon. On the train back to Iowa, he saw many soldiers.

“The soldiers were always kind to kids,” he told his friend of five years, Phyllis Dooley. They passed out snacks and treats.

“He just ate it up,” Dooley said with a laugh. “He thought it was really high living.”

Before he died, he told them how he would love to go back to the Review-Journal and see the linotype machine — the job that brought him to Las Vegas all those years ago.

“I wish I could go back to see those machines,” he told Fiore. “I want to work 40 hours a week, and I want to run the little type machine.”

Contact Briana Erickson at berickson@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-5244. Follow @brianarerick on Twitter.