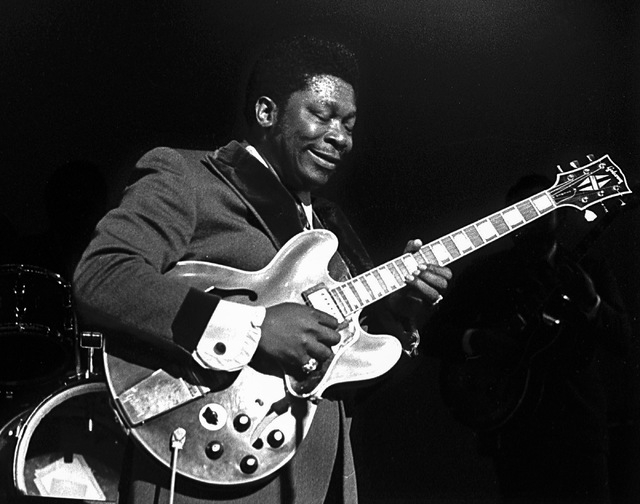

Blues legend B.B. King dead at 89

Legendary guitarist B.B. King, who introduced audiences worldwide to the blues and inspired a generation of musicians, died Thursday night at his home in Las Vegas, his attorney said. He was 89.

“The blues is life,” King said in 2005. But “it’s sort of sad to think you have to be sad” to sing them. “I think the blues are like a tonic,” he added. “They’re good for whatever ails you.”

King had been a Las Vegas resident since 1975. “Vegas was more than a city to me. It represented the ultimate in American entertainment,” he recalled in his 1996 memoir “Blues All Around Me.”

“Being a blues musician has always been like if you was the poor, scrawny kid on the block, and you didn’t have much to say to people, always on the bottom of the totem pole,” he told a Review-Journal reporter during an early morning interview at the keno lounge of the then Flamingo Hilton in 1974.

The former sharecropper helped raise the blues to new heights, taking it from the juke joints and small clubs of the chitlin circuit to Las Vegas lounges and festival stages around the globe.

He developed a distinctive guitar style that made every note count. His biggest hit was “The Thrill Is Gone,” which won him the first of 15 Grammy awards, including one for lifetime achievement.

“When I sing, I play in my mind,” he once described his style. “The minute I stop singing orally, I start to sing by playing Lucille” — referring to his trademark Gibson guitar. His deceptively simple guitar playing, with its string bending and intense left-hand vibrato, inspired such guitarists as Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck, George Harrison, Robert Cray and Bonnie Raitt.

Frank Sinatra was his favorite singer, and King credited him with opening doors to playing Las Vegas lounges in the 1960s.

“I’d started out playing all-black clubs on the edge of Vegas,” King recalled in his autobiography “Blues All Around Me.” But Caesars Palace executives “asked Sinatra whether it was all right for me to play Nero’s Nook, the lounge. ‘Hell, yes!’ he said. Not just yes, but ‘Hell, yes!’ That meant a lot to me.”

King moved to Las Vegas in 1975, long before it became fashionable for showroom performers, and he became a staple in the casino lounges in Las Vegas, Reno and Lake Tahoe. Though his Las Vegas Hilton venue was technically a lounge, it was more a small showroom where King rotated with acts such as Ike and Tina Turner.

Onstage, “I try to be a showman,” he told the Review-Journal in 2005, likening his task to that of an actor whose performance will “take you through these different doors, if you will. But in the end, you leave happy.”

He lived in the Rancho Circle area, where “tourist buses rolled by,” he recalled in his memoir. “It felt prestigious to have my home on that tour. I was the first black in that neighborhood.”

Still, fans were often waving at an empty house, which he kept into the 1990s. “I doubt if I was ever there more than two weeks a year,” he recalled in his memoir, working about 330 dates per year.

In his later years, King brought his big band and the festivals he sponsored to bigger rooms in Southern Nevada. His work on the Strip included the Desert Inn in 1998 and the Stardust in the 2000s. The blues festival that carried his name played three years at the Star of the Desert arena in Primm, and twice at the House of Blues at Mandalay Bay, in 1999 and 2000.

His last Las Vegas performance was the Big Blues Bender festival at the Riviera in September. In 2013, he was part of “Frampton’s Guitar Circus” at the Las Vegas Hotel (now the Westgate Las Vegas).

King was honored by everyone from the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame to the Kennedy Center. Sweden’s King Carl XVI Gustav even presented him the Polar Music Prize, the musical equivalent of the Nobel Prize.

Despite the myriad honors, and decades of audience response to the contrary, “there are nights when I go onstage — I always do my best, but a lot of times my best isn’t as good as what it should be,” King said in 2005. “Everything I do, I think I’m a little weaker than I should be.”

“Most of the blues musicians didn’t go to college or finish high school. I’m one of them,” King told the Review-Journal in 1974, although later he would receive honorary doctorates from a number of universities, including Yale, Brown, Mississippi Valley State and the Berklee College of Music.

Riley B. King was born Sept. 16, 1925, on a plantation in Itta Bena, near Indianola, Miss. He sang duets with his mother in church, learned to play guitar by his teens and played on street corners for nickels and dimes.

“I didn’t know I wanted to do it to make a living,” King said of those early days in his 2005 interview, “but I always loved it.”

He moved to Memphis, Tenn., where he was schooled in the blues by his cousin, Delta blues great Bukka White. King became a star as a singer and disc jockey on Memphis radio, where he was dubbed Beale Street Blues Boy, later shortened to B.B. When he scored his first No. 1 R&B hit, “Three O’Clock Blues” in 1951, he and his band began touring nationally. He toured constantly, once playing 342 one-night stands in a year. He was still averaging more than 200 shows a year into his 70s.

He said the relentless touring cost him his marriages. “I been married twice, both times to beautiful women, good ladies,” he said. “But they just couldn’t understand my work.”

White audiences discovered him in the late ’60s — at the Newport Folk Festival, at the Fillmore West in San Francisco and on tour opening for the Rolling Stones.

Many of his hits, such as “Payin’ The Cost To Be The Boss,” “Everyday I Have The Blues,” “Why I Sing The Blues” and “You Don’t Know Me,” became blues classics. A new generation of fans discovered him through his collaborations with U2, Eric Clapton, Van Morrison, Gloria Estefan and John Mayer.

King has recorded more than 80 albums and played more than 15,000 shows. He was inducted into Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1987 and also is in the Blues and R&B halls. The B.B. King Museum and Delta Interpretive Center opened in Indianola in 2008.

He also opened a string of B.B. King’s Blues Clubs, beginning on Beale Street in Memphis in 1991. One of his clubs opened at The Mirage in 2009 but closed three years later.

King went on an international “farewell tour” in 2006 but continued to perform until last year when he was forced to cancel eight shows because of dehydration and exhaustion due to diabetes. He had been treated at a Las Vegas hospital for several days last month for a similar illness. King had suffered from Type II diabetes for more than two decades and was a spokesman against the disease.

The blues legend informed fans of his final illness on May 1 through his website: “I am in home hospice care at my residence in Las Vegas. Thanks to all for your well wishes and prayers.”

When a Review-Journal interviewer asked him how he’d like to be remembered, King said:

“I’d like them to think that here’s a guy that just loves people, that wants to be wanted, a guy that’s like that next-door neighbor they can depend on. I’d like people to think of me as a friend and yet an artist.”

Review-Journal reporters Mike Weatherford and Carol Cling contributed to this report.