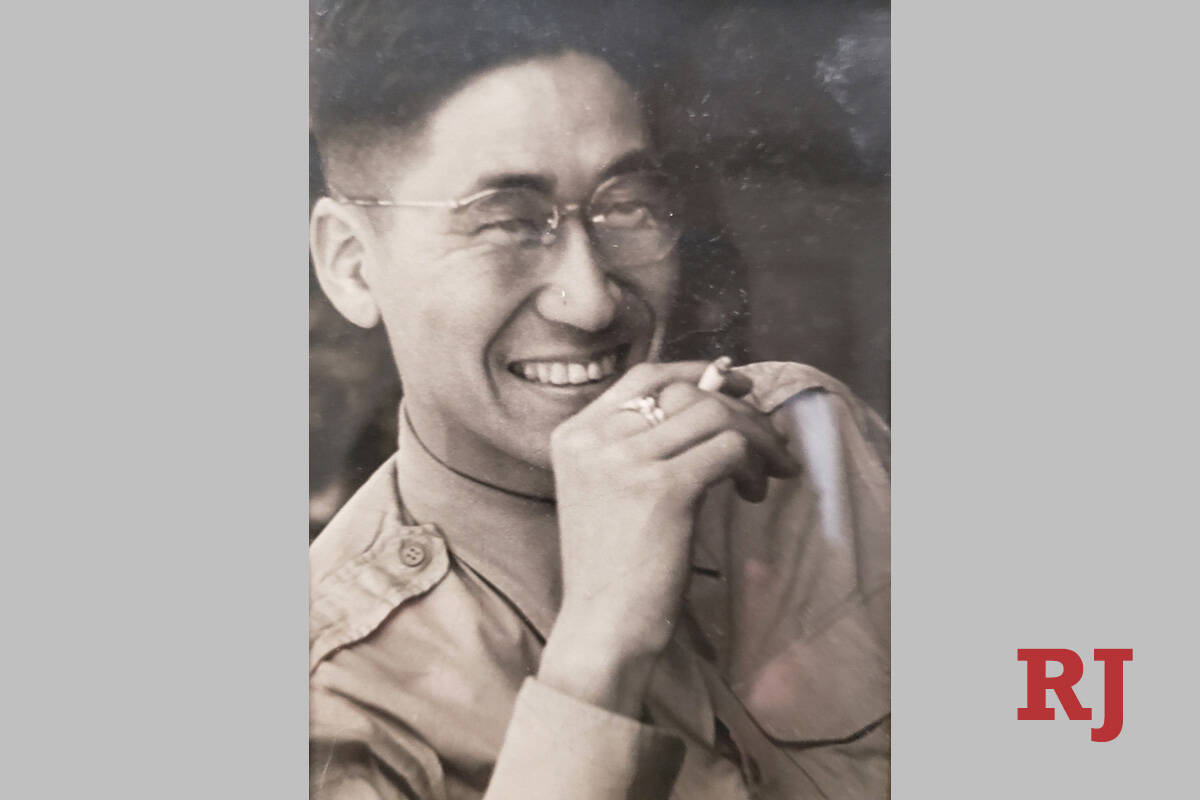

Meet the 105-year-old WWII veteran who was held in an internment camp

Roy Hashimura doesn’t say much anymore, but he never really did.

That’s not to say he hasn’t seen a lot of things in his long life.

Hashimura, who enlisted in the U.S. Army after being confined to an internment camp during World War II because he was an American of Japanese descent, celebrated his 105th birthday on Wednesday.

“I think he just wanted to show that, ‘Hey, I’m an American and I want to serve, and that’s what I’ll do,’” said Hashimura’s son, Charles Hashimura, 70, of Las Vegas.

Charles Hashimura was joined by siblings Lisa Lee, 76, and Margo Brower, 72, at a Wednesday birthday party for their dad at the Las Vegas assisted living facility where Roy Hashimura lives. Also joining them in the facility’s dining room were Margo’s husband, Jay, Charles’ wife, Tracee, and many of the facility’s 140 or so residents.

“So the real reason why we wanted to celebrate Roy’s birthday is because how often does one of our residents turn 105?” said Stephanie Pineda, the “vibrant life director” at Sterling Ridge Senior Living. It was Pineda who organized the birthday party.

Pineda, who was cutting pieces of Oreo chocolate cake, summed up how Hashimura is regarded at the facility in three words: “Everybody loves him.”

With three large gold-colored balloons of the numbers 1, 0, and 5 above him, Hashimura sat in his wheelchair at his own table and quietly ate a lunch of pasta and vegetables before his family arrived for the midday party.

Then someone put a necklace with a fake gold chain medallion that reads “Aged to Perfection” around Hashimura’s neck, everybody sang “Happy Birthday,” and the birthday boy, wearing a hat that read “World War II Veteran” elicited cheers after blowing out all of the cake’s candles.

‘Nicest-hearted guy you’d ever meet’

Hashimura’s three children described their dad as a quiet, reserved man who didn’t talk much about his internment camp or military experience, which included working as a guard at a German prison that housed accused Nazi war criminals.

Now, at his advanced age, Hashimura doesn’t speak much. He is capable of uttering a few words when asked questions, his son said. But even in his younger years, his children said, he was never much of a talker, despite having always been a kind and devoted family man.

“He would do anything for his family. He would do anything for, actually, anybody,” Charles Hashimura said. “The guy was just the nicest-hearted guy you’d ever meet.”

“Good,” Roy Hashimura said, when asked how he was doing on his 105th birthday.

Born in Long Beach, California, on March 20, 1919, Hashimura grew up in Riverside. After his parents, who were both born in Japan, died while Hashimura was young, he was adopted by the Harada family in Riverside, his children said.

The Harada family were themselves influential in American history.

Their home, now known as Harada House, became a “powerful civil rights landmark in California,” according to the Museum of Riverside, and a National Historic Landmark because of its role in a landmark case that “tested the constitutionality of laws preventing immigrants, primarily from Japan, from owning property in California,” according to the National Park Service.

But after the Pearl Harbor attack in 1941, Roy Hashimura and the Haradas were among the more than 125,000 American citizens of Japanese ancestry and Japanese-born immigrants sent to internment camps ushered in by the administration of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt amid a wave of anti-Japanese sentiment.

He was sent to a camp in Poston, Arizona, his children said. His adoptive parents, Jukichi and Ken Harada, died in the camp hospital at the Central Utah Relocation Center, another internment camp, while incarcerated there, according to the Harada House Foundation.

Service to his country

When he was released from the camp, Roy Hashimura signed up with the U.S. Army and was soon sent to Germany in about 1945, around the time of the end of the war. In Germany, part of his experience included guarding Nazis accused of war crimes, his children said.

“He wanted to be a loyal American,” his son said.

While in Germany, he would meet his future wife, Anna Becker, and the two were married. They moved back to the United States, where they raised a family, with the siblings growing up in Norwalk, California. They were married for over half a century, until Anna died in 2002.

In his professional life, he worked as an accountant at Hughes Aircraft, but he also took a part-time job in the produce section of Von’s grocery store, his children said. He also had a passion for fishing.

Now that Roy Hashimura has reached 105, his children were asked how he has been able to achieve such longevity. His son spoke of another media interview with Roy on one of his previous birthdays in which he was asked his secret for living such a long life.

His answer? No stress.

“There were stressful situations, but he wouldn’t carry it,” Charles Hashimura said. “He never carried stress with him everywhere. He would let it go. If it happened today, it’s gone tomorrow.”

Contact Brett Clarkson at bclarkson@reviewjournal.com.