Clark County, state re-evaluate targeted funding for schools

Six years ago, Nevada launched the first of what would become several programs to boost education funding for targeted student populations.

Since then, those initiatives — known as categorical funding — have pumped millions of dollars into classrooms across the state. But have they worked?

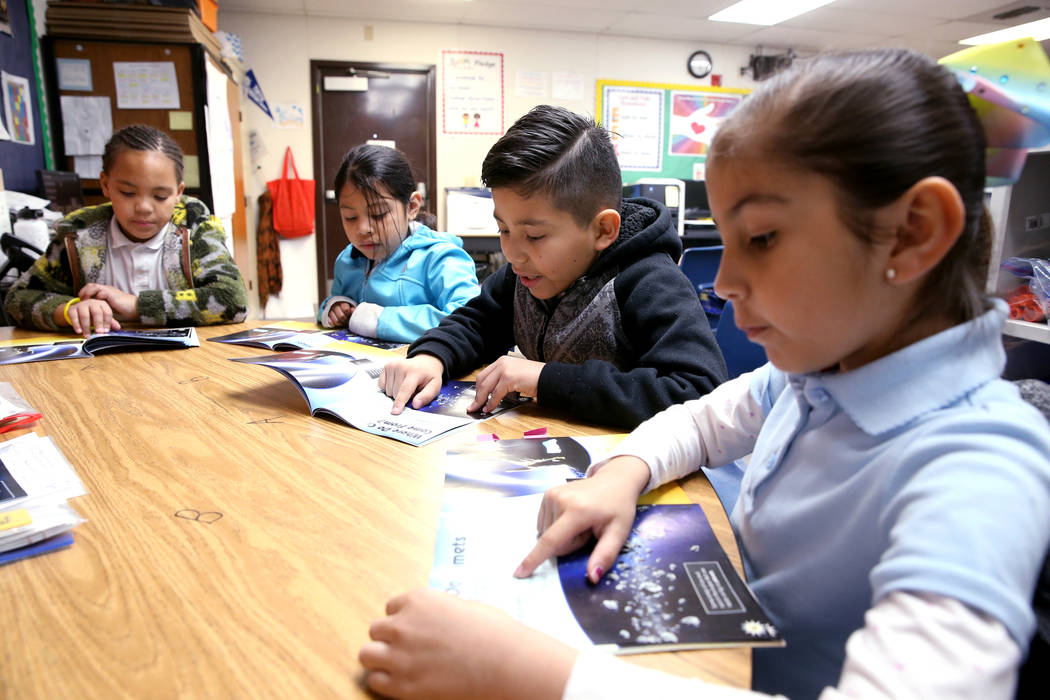

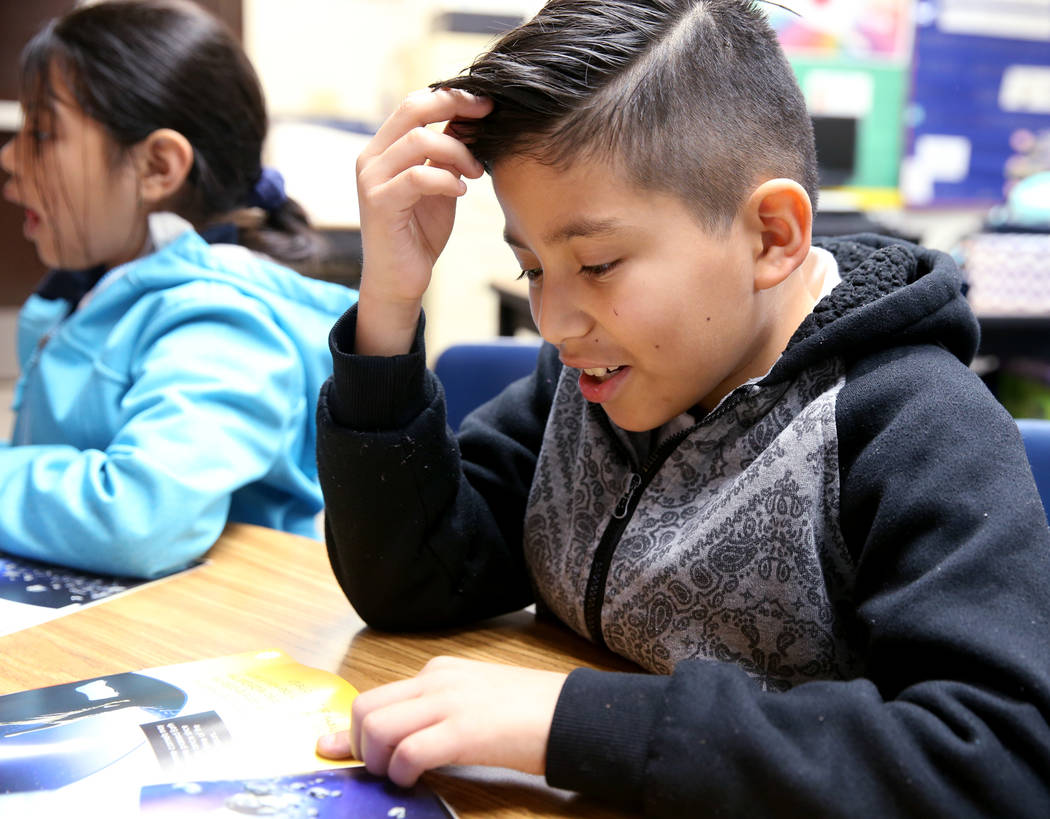

At Tate Elementary School in northeast Las Vegas, the answer is “yes.”

Kindergarten teacher Virginia Mosier saw her classroom size drop from 35 to 21 after the school received Zoom funding, which flows to schools with large populations of English language learners.

Mandated universal preschool under the program means those children are likely coming to kindergarten more prepared. Plus, there is an extra 20 minutes of teaching in the school day.

“With Zoom I’m able to do so much more,” Mosier said. “Before, I would hit all the letters. We’d teach the letters. We’d teach the sounds, and that’s pretty much as far as we got because everything was a lot slower paced.”

The latest external annual report required by the state recommends continued funding for Zoom, Victory and five other programs that seek to improve academic outcomes for specific academically challenged populations.

All the programs, the evaluation concluded, have either shown academic progress or have the potential to do so. The Legislature has reauthorized these initiatives since their inception. They accounted for roughly $251 million in extra money for education for the 2017-19 biennium alone.

But the Clark County School District is taking a closer look at schools receiving Victory funding, which targets high-poverty schools. The district conducted its own analysis that found the schools have not grown in math and English as much as anticipated.

“If we do not take care of our money, the public will not trust us,” CCSD Superintendent Jesus Jara said after reviewing Victory school results at a town hall meeting this month.

History of funding

Since its inception in 2013, the Zoom program has pumped roughly $200 million into 62 low-performing schools across the state, according to the state Department of Education.

The Victory program followed in 2015, providing roughly $100 million over four years to 35 low-performing high-poverty schools.

The Read by Grade 3 initiative, also passed in 2015, has provided about $68 million in grants to over 300 schools to help students reach literacy by third grade.

Those funds can only be used on certain approved programs.

Victory schools have more freedom with how they can spend the money — but they must use it on programs that are proven to improve academics.

Meanwhile, Zoom elementary schools like Tate must have pre-kindergarten programs, longer school days and a reading center.

Tate Principal Sarah Popek said the Zoom program has made a huge difference at the school in six years.

She had a wait list of 40 students vying for a spot in preschool. Now, she accepts all applicants and prepares them for kindergarten, which has a mandated cap of 21 students per class.

“That first week of Zoom, I had kindergarten teachers in tears saying, ‘Oh my god, this is amazing. I can finally teach,’” she said.

The smaller class sizes and additional resources helped Tate improve its academic scores and star ratings.

The school showed the largest gain in “adequate growth percentile” — a measure of academic improvement — out of all elementary schools in the Clark County School District, according to the external evaluation by UNLV, ACS Ventures and MYS Project Management.

Zoom schools improving

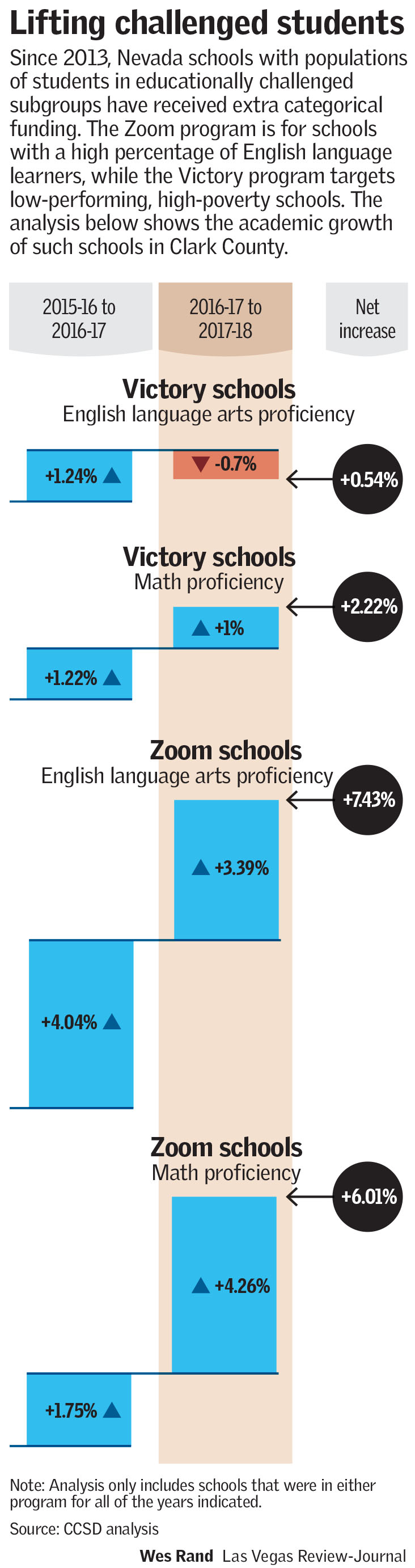

The district’s analysis also showed improvement among Zoom schools. Since 2015-16, math proficiency has grown 7.4 percent while English proficiency has increased by 6 percent, it found.

Victory schools in Clark County also are outshining other low-performing schools that do not receive such funding, according to the external analysis.

But the district assessment concluded that the targeted funding has resulted in a net increase of just 0.54 percent in English proficiency and 2.22 percent in math proficiency.

That’s causing district officials to look closer at the program.

“What’s not working, we’re not doing,” Jara told the School Board last week. “And what’s working, we’re going to accelerate and move into all schools.”

The external state report measures the data differently — breaking down proficiency by grade — and gives Victory schools higher marks than the district’s assessment.

More than half of Victory schools in Clark County have increased their proficiency in math for grades three through eight from 2017 to 2018, according to the analysis. At least half or more have increased reading proficiency in second through fifth grade and kindergarten.

Three of the four Victory high schools have higher graduation rates for the past two years than the statewide average, it said.

These metrics are only one way to measure success, noted Susan Ulrey, an education programs professional for Victory schools with the state. Climate, culture and family engagement — other focus areas in the program — had to be built up in the first year before the schools began seeing academic gains, she said.

Ulrey highlighted one other area of concern: schools that have a strong leader often see that person move to another school.

“The strong leader part is another part that is really needed in high-poverty schools,” she said. “Because that leader has to understand how to put those systems in place in order to increase the academics.”

Funding urged for other programs

The external analysis also recommended continued funding for other targeted education programs.

That includes the Nevada Ready 21 program, which provided $20 million in the 2017-19 biennium to boost technology in schools; the $9.8 million Great Teaching and Leading Fund, which is used to recruit and retain quality teachers; the $5 million Underperforming Schools Turnaround program; and the $22.4 million Social Workers in Schools program that provides licensed mental health professionals.

That will be just one of many requests in the 2019 legislative session, which is expected to focus heavily on education funding.

At Tate Elementary, Principal Popek says success isn’t only about the money. It springs from having effective teachers in the classroom.

But the funding gives those teachers an opportunity to do their best work, she said, adding that she hopes legislators will heed this message: Don’t eliminate Zoom funding, and don’t penalize schools that are on a successful trajectory by taking away the money.

She also said additional funding would allow her at-risk population to grow even faster. As a Zoom school, for example, Tate does not receive additional “weighted” funding for students in need, she said.

“We need more money,” she said. “Money needs to flow down to the schools, because that’s where everything else starts.”

Contact Amelia Pak-Harvey at apak-harvey@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-4630. Follow @AmeliaPakHarvey on Twitter.