Hatchery victim of mussels

They've already caused operators of dams and hydroelectric plants on the lower Colorado River system to brace for millions of dollars in maintenance and repair costs.

And they've frustrated boaters in the Lake Mead National Recreation Area as millions of them cling to vessel hulls and engine cooling water intakes.

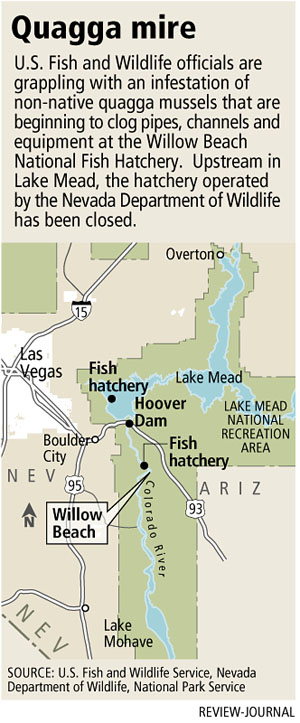

And now, invasive quagga mussels, which were discovered in Lake Mead's Boulder Basin on Jan. 6. 2007, are starting to clog up the works at the Willow Beach National Fish Hatchery.

The federal hatchery, where thousands of rainbow trout and endangered fish are raised, is on the Arizona side of Lake Mohave, 14 miles southeast of Hoover Dam.

"The problem is that anywhere there is no (strong) flow, quagga mussels will establish themselves in the screens, pipes, wood boards and walls of the raceways," hatchery manager Mark Olson said.

As he spoke Wednesday, one of his co-workers for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Mark Yost, used a power washer to blast quagga mussel shells off a drained concrete channel, or raceway, where rainbow trout once swam.

The problem stands to be as prolific as the reproduction rate of the pesky mollusks themselves. Since the first quagga shell was found at the hatchery a little more than a year ago, millions more have multiplied.

Olson said the hatchery, where 300,000 rainbow trout and 20,000 endangered razorback suckers and 35,000 bonytail chub are raised, faces a problem that could cost $2 million to $5 million to fix if the facility is converted to well water or a treated water supply that is free of quaggas, unlike raw water from Lake Mohave that is used for most hatchery operations.

The quagga problem is not expected to affect the quality of trout fishing at this point. Wildlife officials continue to stock the lakes with hatchery-raised trout. For some bodies of water in Southern Nevada, Nevada Department of Wildlife officials are bringing in trout from hatcheries in Northern Nevada.

A few hundred hybrid pupfish, a cross between the endangered Devil's Hole pupfish and the Ash Meadows pupfish, are raised in aquariums that are filled with well water and are not affected by quagga mussels.

Fingernail-size quaggas and their cousins, zebra mussels, were released in the Great Lakes region in the mid-1980s after hitchhiking in the ballast water of ships from eastern Europe and the Ukraine, where they are native to Ukraine's Dneiper River drainage.

Biologists think quaggas arrived at Lake Mead sometime before January 2007 by traveling in bilge water or on the equipment of a boat from the Midwest that was launched in the lake. From there, they spread rapidly throughout the lake and downstream to lakes Mohave and Havasu.

Because of ideal conditions in the lakes on the lower Colorado River system with the right mix of food, calcium, dissolved oxygen and water temperature, quaggas have a reproduction rate three times that of those in the Great Lakes region. They reproduce six times a year instead of two, and a single female lays as many as 1 million eggs.

Once colonies are established, they can clog water lines and cause pumps to overheat.

Of the $600,000 that's budgeted annually to operate the 45-year-old hatchery, no money is devoted to dealing with clogged pipes and equipment, Olson said.

The problem "is indefinite," he said. "I don't see it going away. They didn't go away in the Great Lakes. We just have to come up with a management strategy that works and stick with it."

A trout hatchery on Lake Mead, operated by the Nevada Department of Wildlife, was shut down in the spring of 2007 because of the quagga infestation and dwindling lake levels that left the water intake for the hatchery at a shallow depth, too warm for raising trout.

After the last trout stocking release was completed, some of the operation was transferred to the Willow Beach hatchery, where raceways and nearby pens in Lake Mohave were made available.

Nevada wildlife officials are drawing up plans to put the Lake Mead hatchery back in operation.

"The ideal situation to us would be to be able to hook up the Southern Nevada Water Authority pipeline," said Jon Sjoberg, supervising fisheries biologist for the Nevada Department of Wildlife's Las Vegas office.

"It would be cleaner and cooler water," he said, explaining that to raise trout in water above 65 degrees is problematic. In the summer, the lake's water at the existing intake can be as high as 75 degrees.

The water authority draws its water from deeper, colder depths from intakes at Saddle Island. The water then undergoes a treatment process that would kill quaggas and their larvae.

The Nevada Department of Wildlife would need a mile of pipeline constructed in the Lake Mead National Recreation Area for the water to reach the hatchery.

"I guess we're a year or two away to be able to do that," Sjober said.

"It's not cheap. We're working on estimates. It's our water right, but somebody has to convey it to us," he said Thursday.

State and federal hatchery operators are not alone in their struggles to deal with quagga mussels.

The Bureau of Reclamation, which operates dams on the lower Colorado River, is making plans for coping with the infestation. Once the mussels clog hydroelectric cooling pipes and other hardware, the maintenance-and-control bill could reach $1 million a year just at Hoover Dam.

Meanwhile, the National Park Service is midstride in its effort to educate boaters about cleaning their vessels to rid them of mussels and larvae before they are transported to waters that have not been affected by the invasion.

The Don't Move a Mussel awareness campaign parallels efforts to avoid potentially dangerous situations from boats berthed at marinas in the Lake Mead National Recreation Area.

Without regular maintenance to brush away the mussels, colonies can build up on the hull and in the cooling water intakes. The fear among recreational boaters is that skippers who haven't done the maintenance will risk serious safety hazards caused by drag on the boat and lack of cooling water.

In such a case, the boat's engines would overheat, melt hoses and catch fire, or the boat would lose power and become adrift in strong winds over the lake's deep water.

On all fronts, biologists, boaters and dam operators alike are searching for a natural solution, a predator that thrives on quaggas.

Olson said one might have been found in recent months, the redear sunfish.

"It's been documented that redear sunfish will eat them," he said, referring to a species of panfish that thrives on clams and snails.

Recently in Lake Havasu, he said, quagga mussels have been extracted from the bellies of sunfish caught in the lake.

The question is: Are there enough sunfish to counter the millions and millions of quagga mussels that have their grip on the lower Colorado River system?

Contact reporter Keith Rogers at krogers@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0308.

ON THE WEB:

View the audio slideshow