Normandy 70th anniversary moves one Nevada vet, sparks memories of another

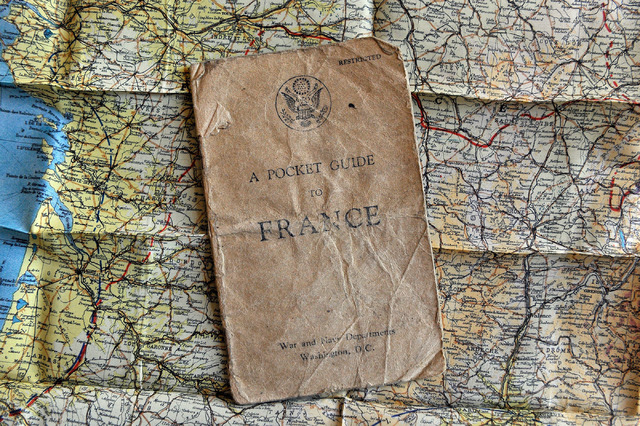

It was “D-plus-3,” or June 9, 1944, when Army Pvt. Ed Jennings landed with his field artillery battalion at Utah Sugar Red Beach near St. Mere Eglise, three days after the allied D-Day invasion on France’s Normandy coast.

Jennings, a curly red-haired soldier assigned to the 5th Infantry “Red Diamond” Division, would write home to his parents in Massachusetts about the experience days later.

“I am in a foxhole just as far below the ground as I can get,” he wrote in one of the 110 now-yellowed letters he penned in blue ink and pencil from the battlefield. “And this is the safest place to be for those German 88s are really rugged. Naturally censorship is very strict and I can tell you practically nothing except that the present moment I am all right.”

Forty years after the historic landings, while dying from leukemia in Las Vegas, he yearned to mark the D-Day anniversary and see then-President Ronald Reagan deliver his commemorative speech where Army Rangers scaled the cliffs at Pointe du Hoc with death-defying acts of heroism. But he was too sick to make it.

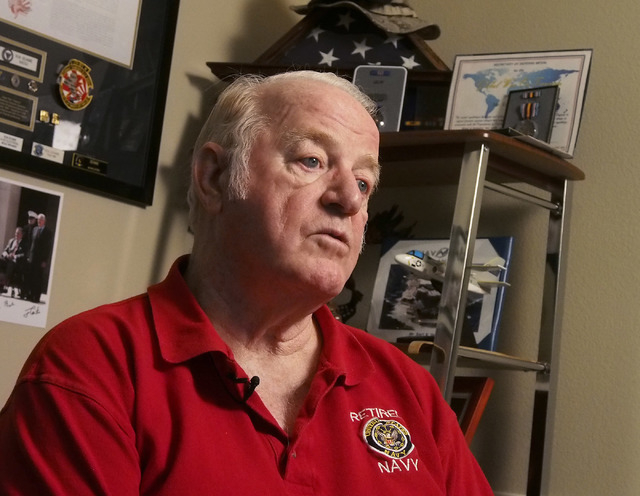

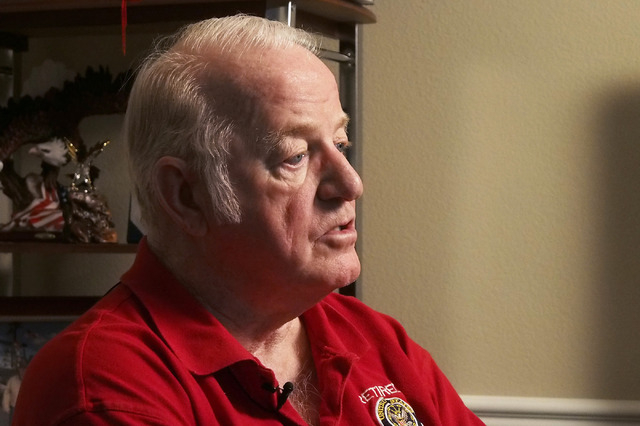

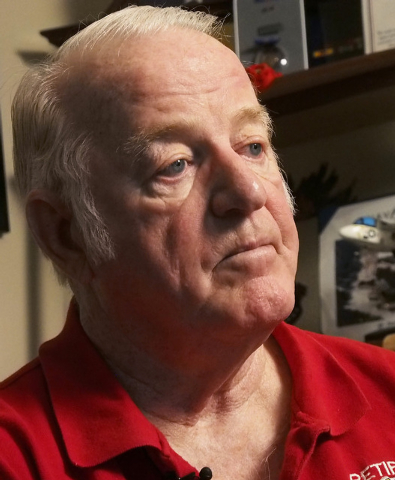

So in a few days, 70 years after the invasion of Normandy, career Navy veteran Ron Deanne, of Henderson, will do what Jennings couldn’t do in 1984 and pay his respects to him and soldiers who died there.

“I wanted to take the memory of Pvt. Ed Jennings and fulfill Ed’s wish for the D-Day celebration,” Deanne said before he left for Europe in May. “For me, it’s not only a personal journey and a bucket list item but it’s a fulfillment in Ed’s spirit that I visit Normandy and the whole area where Ed was.”

SAND FOR SOLDIER’S WIDOW

In an email Friday from Germany where he was traveling with his wife, Anita, en route to Normandy, Deanne said he will bring back some sand for Jennings’ widow, Fern, of Las Vegas, who is a tap dancer with the senior women’s patriotic troupe, the Happy Hoofers.

The token jar of sand from the Normandy beaches will complement the Mason jar of water from the Danube River that Pvt. Jennings brought home in 1945 after his battalion fought its way to Germany.

Deanne, a Navy aircraft electrician whose combined 39-year military and civilian career spanned four wars from Vietnam to Afghanistan, had already planned a trip to Normandy to see where his Army Ranger heroes made their assault on Pointe du Hoc.

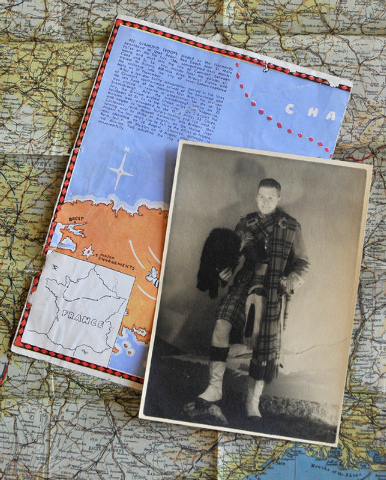

But after reading a Review-Journal story in December about Fern Jennings’ book, “Your Loving Son, ‘Ed,’ ” about her late-husband’s World War II letters that she published for the 50th D-Day anniversary in 1994, Deanne decided to retrace Jennings’ steps as the 5th Infantry Division of Lt. Gen. George S. Patton’s Third Army chased Hitler’s Nazi forces through towns and forests in France, Luxembourg and Germany.

Fern Jennings said her husband’s dream was to return to Normandy.

She said it was “kind and sweet” of Deanne to devote his trip to the travels of Pvt. Jennings. “I thought that was one of the kindest things, and I’m sure Ed would have been really touched by it. Ron is a wonderful man to even think about doing something like that. I’m anxious to see when he comes back what he’s got to say.”

Deanne, whose father was a World War II aviator in the Pacific Theater, is fascinated by military history and has watched “The Longest Day” and “Band of Brothers” many times.

“The significance of that landing was to show the world that you just can’t take over everybody’s country,” he said.

“It’s always been a bucket list item of mine to pay my respects to the Army Rangers that climbed the cliffs of Normandy to get to the Germans,” he said. “I’ve always wanted to honor and pay homage to those brave young men who did that. I’ve always thought that had to be one of the most difficult parts of the war to be climbing a rope ladder while people are shooting down at you and cutting the ropes.

“To me those young men just were brave beyond control,” he said about the assault group from the 2nd and 5th Ranger battalions, whose landing force of more than 200 was reduced to about 90 soldiers.

SPECIAL OPS FOR D-DAY

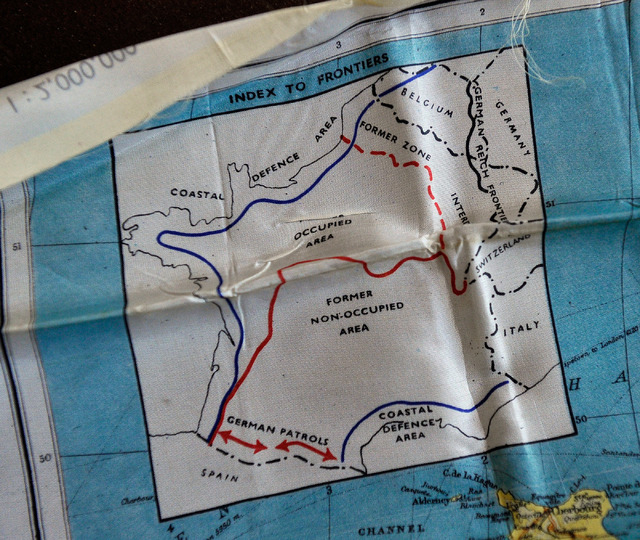

Besides the historic landings that spanned 50 miles from the British at Sword Beach to where Pvt. Jennings came ashore at Utah Beach, Deanne noted the importance of many secret, behind-the-scenes operations to fool the Nazis so “they did not know which area they were going to land.”

“They used paratrooper dummies so when they hit the ground they gave out a gunfire noise so the Germans would think this was where they were going to land when, in fact, a lot of the paratroopers and gliders landed behind enemy lines in areas where they did not know where they were,” he said.

Special operations behind the lines had been in the works for weeks before the invasion, preparing French freedom fighters for long-haul battles that would follow.

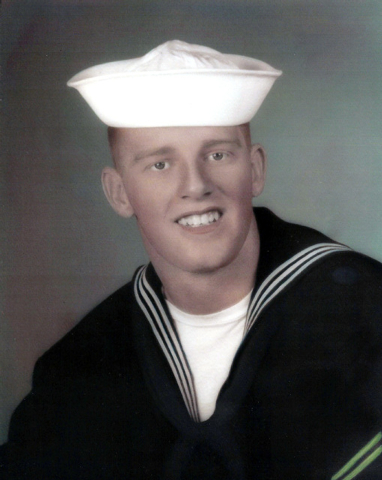

Tom Norman, 92, of Las Vegas, remembers well the secret missions of his 885th Bombardment Squadron of the Army’s 15th Air Force Special Group. He was an Army second lieutenant navigator-bombardier in a B-24 Liberator that flew 50 night missions over France before and after D-Day in 1944.

But he never dropped a bomb or fired a shot. His B-24, dubbed, Pocahontas, had been painted black and modified. “They took out the guns in the front. I couldn’t shoot anybody.”

Instead, they air-dropped special agents, “Joes and Josephines,” he said, with parachutes to organize the French underground army and supply them with tons of guns and ammo.

On one mission, 11 aircraft from his squadron dropped 18 special agents and “67,000 pounds of arms, ammunition and special supplies to units of the hard pressed French Forces ... at clandestine targets scattered throughout Southern France,” according to his Distinguished Unit Badge citation from Maj. Gen. Nathan F. Twining on Nov. 1, 1944.

The air crews navigated by stars “in the complete darkness of a moonless night.” The agents, arms and ammo were successfully dropped for immediate use by the “French Forces of the Interior ... in the support of the pending invasion.”

“In addition 225,000 leaflets, alerting the population of three large cities in Southern France, were dispatched,” the citation reads, adding that “Maquis,” or rural guerrilla bands of French resistance fighters, provided “invaluable aid to the Allied invasion of Southern France.”

Norman on Thursday recalled how the night flights were conducted.

His B-24 would make a 1,200-mile round trip from Blida, Algeria, in North Africa, flying over the Mediterranean Sea and into Southern France at 1,000 feet or even 500 feet above ground. They were so close to tree tops, sometimes they’d land back at Blida with twigs caught in the wings’ flaps.

Norman said his job was to spot the three bon fires in a row that “the reception committee” would light in low-lying areas to mark the drop zone. “At the last one was a Frenchman flashing a Morse code letter with a flashlight,” he said. “If it wasn’t the right letter, we didn’t drop.”

On the eve of the D-Day landings as the invasion was unfolding, Norman noticed German trucks that typically travel at night without lights to conceal their movements were driving with their lights on.

“We were going over France and all the Germans had their lights on and we didn’t know why. They were going toward Normandy,” he said. It wasn’t until his squadron returned to Blida and they reported this during the debriefing that his commander revealed that the invasion was underway.

“I was trying to figure out what they were doing that for all of a sudden because we weren’t used to seeing headlights on a truck going west,” he said. “I never realized that it was D-Day. I never gave it a thought. I just thought something was going on with the Germans. Maybe it was Hitler’s birthday. I don’t know.”

Norman said to him D-Day meant there “was a lot of men being killed. A lot of my fellow friends got killed. It also meant the freedom for Europe.”

Contact Keith Rogers at krogers@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0308. Find him on Twitter: @KeithRogers2.