Nye County: home to Shoshone, Paiutes before miners, scientists arrived

Editor’s Note: Nevada 150 is a yearlong series highlighting the people, places and things that make up the history of the state.

Before it was Nye County, the first inhabitants referred to that sparsely populated swath of what became Nevada as part of the land of “Newe Sogobia,” the Western Shoshone words for “people of Mother Earth.”

A map of the area about the time the 1863 Treaty of Ruby Valley was forged between the United States and the Western bands of the Shoshone nation shows it stretched over one-third of the Silver State. Today, Nye County at more than 18,000 square miles is the largest in the state and the third-largest county in the United States outside of Alaska.

Time has left its mark on the land. From etchings in stone and symbolic paintings left on walls of wind caves by ancient American Indians, to remnants from gold-and-silver mines, to hundreds of pock marks — subsidence craters — from underground nuclear weapons tests, Nye County’s past and recent history are preserved in its landscape.

After Western Shoshone, Paiute people and Anasazi travelers came early on to trade, hunt deer and gather pine nuts, they were followed by miners of the gold rush era.

Finally, government scientists and technicians converged on Nye County to test atomic bombs and study where to put the nation’s most potent nuclear waste in a volcanic-rock ridge called Yucca Mountain.

In retrospect, it was the Nevada Test Site that put Nye County in the crucible of international controversy and ushered the nation through the Cold War. The Nevada Proving Ground was established by President Harry Truman in a memorandum on Dec. 18, 1950.

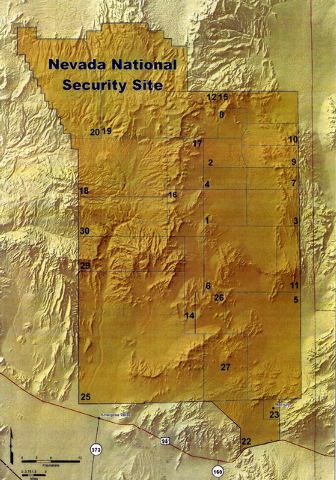

Originally 640 square miles, the grounds were renamed the Nevada Test Site four years later. On Dec. 31, 1954, its area was nearly doubled in size to 1,350 square miles.

A realignment of the site’s boundary in 1999 transferred the Department of Energy’s mysterious Area 51 Groom Lake rectangle on the test site’s northeast corner to the Department of Defense.

The addition put a jagged edge on the Pahute Mesa area and expanded the test site to its current size of 1,360 square miles. Its name was changed to the Nevada National Security Site on Aug. 23, 2010, to reflect its expanded, post-Cold War era missions.

The test site was where some of the largest manmade craters were formed and some of the world’s deepest shafts were cut; where 9,000 troops trained; where some of the largest and most spirited nuclear protests were held; where some of the nation’s most futuristic technologies were tested; where astronauts learned to drive lunar buggies for missions on the moon; and where some of the most deadly poisons were released.

Part of Yucca Flat also was transformed into mock towns, built only to be blasted into dust.

A century before the test site thrust Nye County into the international spotlight, struggles erupted between Western Shoshones and travelers from the East they called “taibo.”

The discovery of gold in California in the late 1840s had a dramatic effect on the Western Shoshone way of life. In 1849 alone, more than 100,000 Americans traveled to California, with about 60,000 of them traversing Newe Sogobia territory.

Livestock the prospectors brought along ravaged the land. Hunters took more game than nature could replace. And, unruly “invaders” used Indians for target practice and sexually abused women, according to Western Shoshone leaders.

This resulted in raids by the Shoshones to take horses and weapons from the settlers, making travel across the territory dangerous. The first attempt at a treaty in 1855 failed to get approval from the Office of Indian Affairs and wasn’t ratified by the Senate.

Finally, a treaty crafted in 1863 was approved by Congress because of the need for a safe route to the California gold fields to finance the Civil War. It allowed U.S. citizens to travel through Western Shoshone territory unmolested to mine, ranch and create agricultural settlements. It didn’t transfer title of the land to the United States, however, an issue that simmers today as tribe members routinely challenge federal activities at Yucca Mountain and the test site.

STATEHOOD IN 1864

With statehood in 1864, Nye County was established and named for James W. Nye, whom President Abraham Lincoln had appointed three years before as the first governor of the Nevada Territory. The boundaries of the county changed six times before arriving at its current configuration of more than 18,400 square miles.

According to Christina Nye Carroll, an 11th-generation niece of James Warren Nye, Lincoln’s role in boosting Nye’s political career from territorial governor to U.S. senator stems from Nye’s effort to make Nevada a Union state.

“That was important to me as a kid growing up,” she said, recalling her show-and-tell school days.

“Still to this day, when I drive through where it says ‘Nye County,’ it makes me proud,” said Carroll, a former longtime Las Vegas resident who now lives in Reno.

Nye was in the U.S. Senate from late 1864 until March 1873. For a while, Samuel Clemens, also known as author Mark Twain, was Nye’s secretary until the senator relieved him of duties for letters on touchy issues Twain wrote to constituents that rubbed Nye the wrong way.

The Nye County seat moved from Ione to Belmont in 1867. That was about the same time land that later became the Nevada Test Site was used by native hunters and pine-nut gathers. Desert Research Institute archaeologists who combed many of the 5,000 archaeological sites inside the site’s restricted boundaries have found brass-rimmed, .44-caliber shell casings for bullets used in vintage-1866 rifles.

The county seat was moved to Tonopah in 1905 during the peak of the mining boom, which saw the county’s population rise from 1,140 in 1900 to 7,513 in 1910, when it was in decline, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

Much of what is known about 19th century life in the area was documented by ethonographer Julian H. Steward, who spent 10 months during 1935 and 1936 interviewing Western Shoshones. Based on interviews with a Shoshone man named Tst, who was 70 at the time, Steward reported there were nine Western Shoshone camps in 1880 in the Belted Range springs, east and south of Pahute Mesa. Another six camps existed near what is now Beatty, including one called Sakainaga, or “willow” on the Amargosa River.

Archaeologists believe American Indians arrived in the area 900 years ago, although human presence at Whiterock Spring goes back 7,000 years.

Steward reported that a regional chief, Wandawana, lived there with his wife, her sister and five children. Wandawana led fall rabbit drives in which braves carrying torches encircled a 1-mile area in the flats south of Whiterock Spring.

The hunting tradition was continued at the test site into the 1950s, when a bronze-faced Western Shoshone man, Ted Shaw, recounted in a 1993 interview with the Review-Journal how he was among the last from his tribe to hunt mule deer on the test site even during the early years of atmospheric nuclear tests.

“We went on anyhow, for about three or four years,” he said at his home near Ely, a year before he died.

“Radiation made the land sick,” he said, with a stare as cold as the February snow outside his window. “It won’t recover.”

NUCLEAR AGE

The first nuclear blast at the proving ground happened in the predawn darkness of Jan. 27, 1951, when a B-50 Superfortress dropped a 1,000-pound atomic bomb, dubbed Able. It fell through the chilly winter air and exploded before it hit the dry lake bed at Frenchman Flat, sending out a blinding white flash followed by a red-orange glow and a shock wave. A mushroom cloud rose 14,000 feet, and a thunderous burst reverberated across the Mojave Desert.

It set the stage for hundreds of nuclear tests to follow, 928 in all through 1992, including 100 that were above ground, and accounting for 1,021 detonations because some of the tests involved multiple devices.

In terms of full-scale nuclear tests, the Nevada site by far hosted more than any place, with the Semipalantinsk site in the former Soviet Union a distant second at 456.

Employment at the test site peaked at 11,000 workers near the end of the Cold War in 1989 when its budget reached $1.4 billion. That was two years after scientific studies were launched at Yucca Mountain, straddling the southwest edge of the test site, to determine if it was safe for entombing spent nuclear fuel from power reactors.

A 5-mile-long exploratory tunnel loop was bored into the mountain; but after spending more than $14 billion from a ratepayers’ nuclear waste fund, the project was abandoned by the Obama administration in 2011. That prompted a blue-ribbon panel to search for other ways to dispose of the nation’s highly radioactive waste.

The last full-scale nuclear test in Nevada, Divider, was conducted on Sept. 23, 1992. After that, President George H.W. Bush launched a temporary moratorium that was extended indefinitely by President Bill Clinton.

President John F. Kennedy was the only sitting U.S. president to visit the test site. His plane landed at Indian Springs airfield, and he arrived at the test site in a touring car on Dec. 8, 1962, to observe a nuclear-powered rocket project. He later signed the Limited Test Ban Treaty on Oct. 7, 1963, that prohibited above-ground nuclear tests.

Prior to going underground, a peaceful-use nuclear device to demonstrate seaport harbor creation was assembled by mechanical engineer Troy Wade.

Buried 635 feet below the surface in a remote area, the thermonuclear bomb was detonated on July 6, 1962, displacing 12 million tons of earth. It left a crater 320 feet deep and 1,280 feet in diameter. The Sedan Crater is on the list of national historic places.

From 1986 through 1994, the test site became a magnet for demonstrators protesting nuclear proliferation and health impacts from atomic bomb development. Tens of thousands congregated at Peace Camp on the road to the government town, Mercury, and more than 15,740 were arrested.

The demonstrations tapered off as the United States in 1997 started conducting subcritical nuclear experiments using high explosives to slam tiny bits of plutonium to see how they respond to check the aging stockpile.

The Nevada National Security Site’s mission to ensure safety and reliability of nuclear warheads continues today. In addition, the site serves other national needs: counterrerrorism, homeland security, nuclear treaty verification, and disposal of certain wastes from cleanup of the Cold War U.S. nuclear weapons complex.

Contact reporter Keith Rogers at krogers@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0308.

Nevada Test Site 60th Anniversary (2011)

Videos, slideshows, timeline, resources