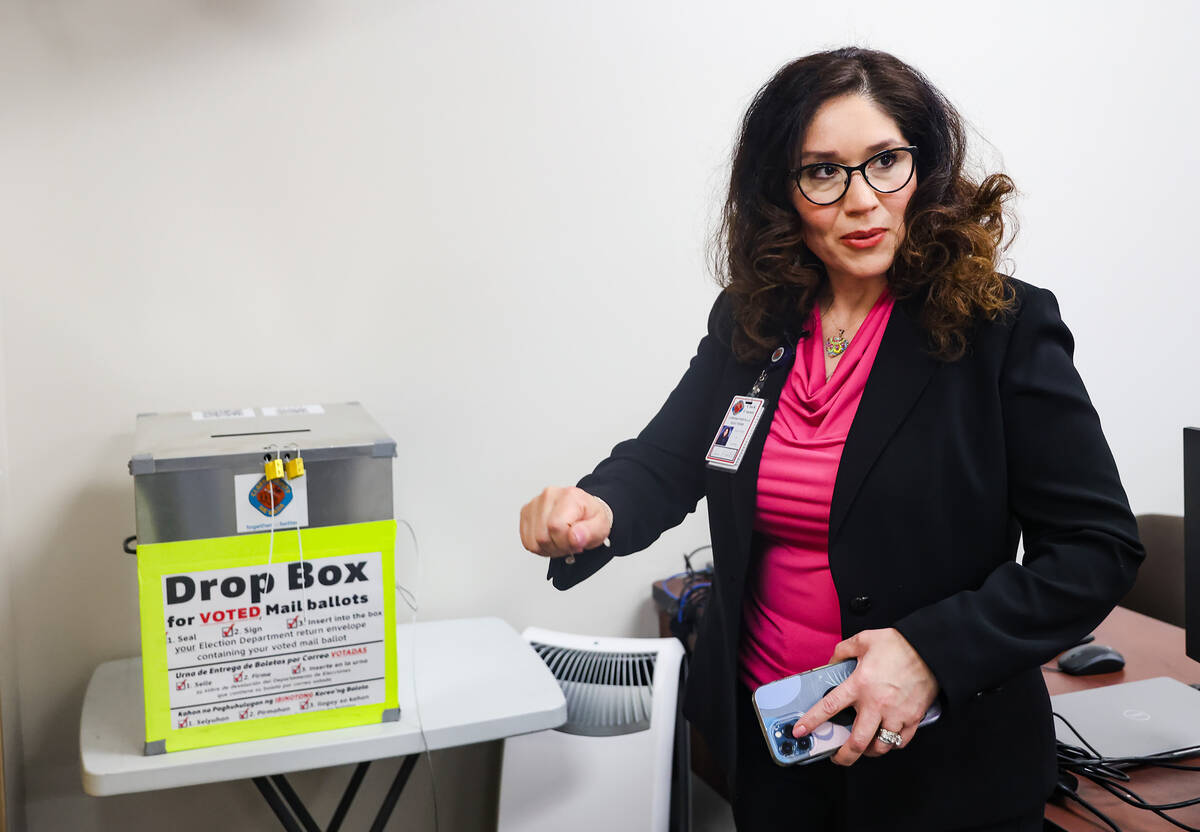

2024 election: How Clark County counts your vote

Running an election in Nevada’s largest county requires hundreds of workers and specialized equipment to sort through hundreds of thousands of mail ballots.

Whether a voter shows up to a polling location or cast their ballot through the mail, there’s a machine at every step of the way.

Once someone drops off their mail ballot, for instance, that piece of mail goes through machines that take photos of the envelopes, sorts and separates and reviews them before passing through equipment that ultimately tabulates the votes. All the while, around 46 permanent staffers and 3,000 temporary workers in Clark County’s election department work with the equipment to count ballots and post election results.

Here’s a closer look at the machines that make Clark County’s elections run, and the companies behind them.

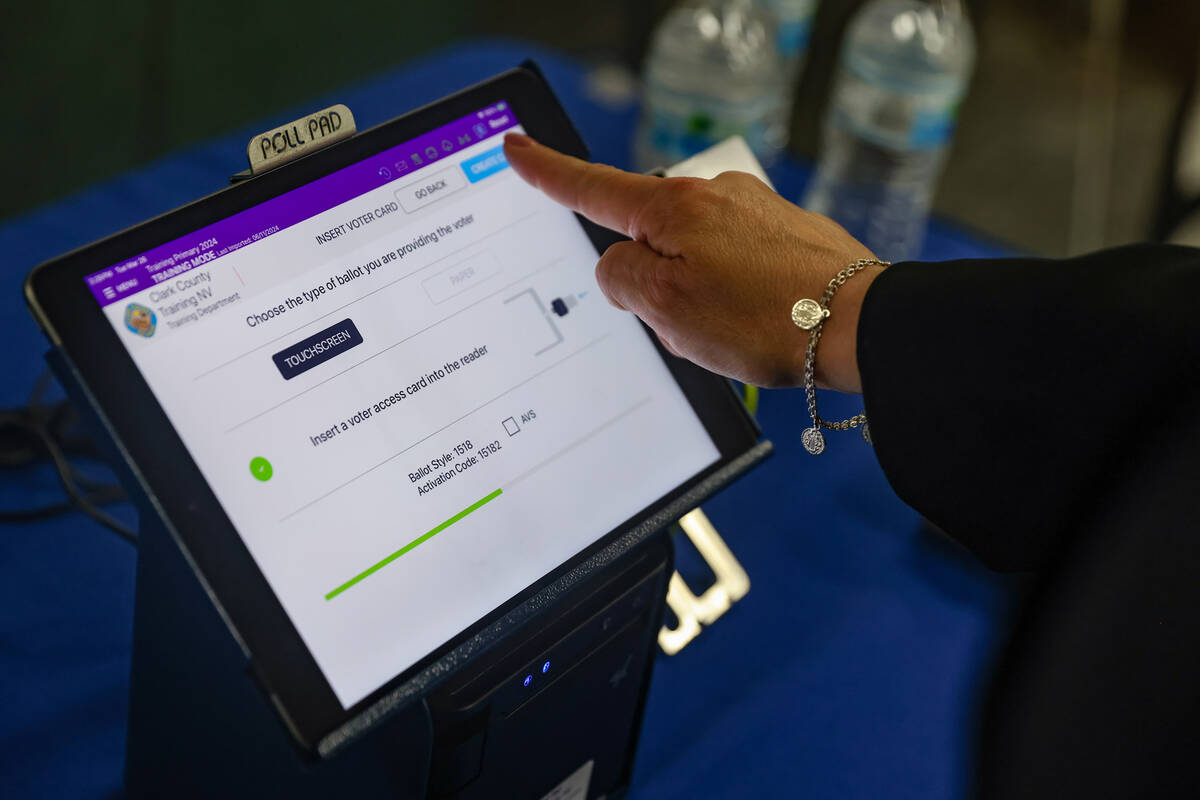

Voting in person: The poll pad

When a voter comes into a polling location, they first check in with an electronic poll book known as a poll pad that brings up their information, including their name, address and political affiliation.

The poll pad is from KNOWiNK, a company that develops election technologies. It has a safe VPN that interacts with the voter database and updated in real-time, according to Clark County Registrar of Voters Lorena Portillo.

KNOWiNK’s poll pads are used in 36 states, with more than 122,000 poll pads used in over 1,800 jurisdictions, according to its website.

As voters use the poll pad, a warning pops up reminding voters that voting twice is a crime, and that even attempting to vote twice is a crime. The voter must hit the ‘accept’ button before proceeding.

Next, the voter’s information appears, and they are asked to confirm their information is correct. The voter must say if they received their mail ballot — which is delivered automatically to voters unless they opt out — and say whether they will surrender it to the polling location. If they left their mail ballot at home, they must sign an affirmation saying they will not use it. Then the voter signs the poll pad, and the signature is added to their voter registration record.

The poll worker will then turn the pad around and verify that the voter’s signature matches the signature on file. If it does not, the poll worker asks a series of questions and may ask for the voter’s ID, Portillo said.

After the voter’s information and identity is confirmed, a plastic card used in the voting process is activated, and the voter takes it up to one of the voting machines.

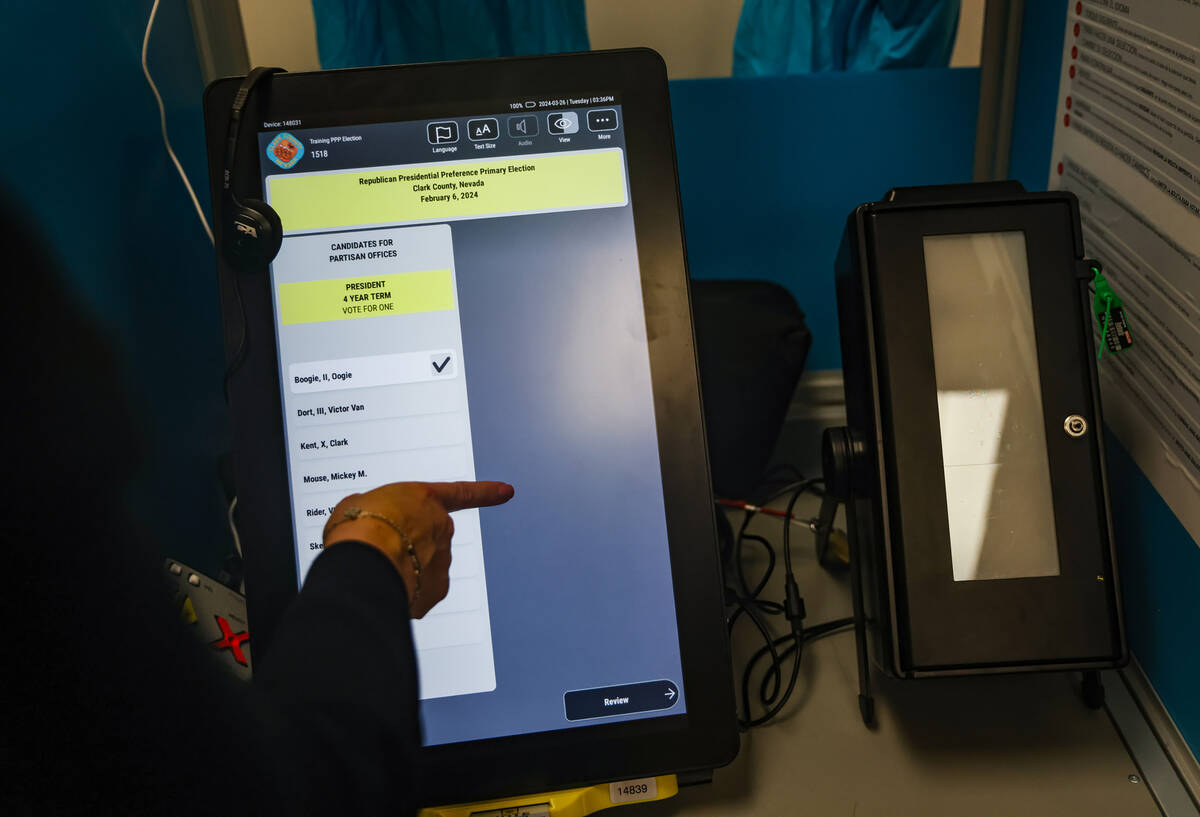

Voting in person: The voting machine

Clark County uses ImageCast X, or ICX, a Dominion Voting Systems machine. Dominion partners with more than 1,300 jurisdictions, including nine of the 20 largest counties in the country.

Portillo said the machine is the “latest and the greatest” in the industry. One of the biggest misconceptions about the voting machine is that it’s connected to the internet, she said. But that is incorrect; it’s not even connected to another machine, she said.

Voters can cast their vote in just one contest, or in every contest up for election. They can review their vote before submitting. When they submit their vote, the vote is saved on a flash drive inside the ICX machine, which election officials take out every night during early voting as well as on election night, Portillo said. The county is also investing in trackers for each of the flash drives, she said.

Along with the vote recorded in the flash drive, a paper record is also printed in what is called the Voter Verified Paper Audit Trail, or VVPAT, that sits next to the voting machine. That is also a Dominion product.

The VVPAT printer serves as a corresponding paper record copy of a vote in the form of a receipt is used for audits, Portillo said. There’s a QR code on each receipt, and election workers make sure it matches with what’s on the receipt, she said.

Voters remove their plastic card and put it in a secure drop box before they leave. The card only contains the information on their precinct and whether they voted, Portillo said. The card becomes inactive after about an hour, she said.

Voting by mail: The mail ballot envelope sorter

All completed mail ballots are brought to one room in the Clark County Election Department in North Las Vegas, where they pass through the Agilis ballot sorting machine, which takes a photo of each ballot envelope.

Made by Runbeck Election Services, Agilis can sort up to 18,000 mail packets per hour, according to Runbeck’s website. The machine scans for voter signatures and saves them for voter records.

After the envelopes are scanned, the Agilis machine runs the envelopes through a “first pass scan” that sorts the envelopes into either “good” or “reject” categories, according to Runbeck. Envelopes go into the “good” section if they meet predetermined qualities, such as if they have the right dimensions, if the voter was found in the system and if the voter is determined to be eligible to vote.

Envelopes that go into the “reject” category were either too thick or too thin, had incorrect dimensions, or were missing or had an invalid bar code. Rejected envelopes go through a manual process, Portillo said, where a bipartisan team determines the issue, such as if the envelope is missing the ballot inside, or if there are two ballots inside.

If the signature doesn’t match, the envelope is flagged for manual signature verification, where a bipartisan team reviews the last signature on record. If that doesn’t suffice, they review all signatures on file, Portillo said.

Some envelopes have to go through the signature curing process, where the county alerts the voter through email and text alerts that their signature needs verifying. In the 2020 general election, for instance, 12,584 mail ballots needed a signature cure in the state, or about 1.82 percent of mail ballots, according to the secretary of state’s office.

The envelopes are then run through the Agilis machine again in the “audit pass process,” Portillo said. Through that step, election workers capture any possible change to the voter record, she said.

All information that goes through the Agilis machine goes back to the voter registration database to give voters credit for participating in the election in the form of a text file, according to Runbeck.

Voting by mail: The ballot separator

Next up in the mail ballot’s journey is a trip through the OPEX machine, which separates the envelope from the ballot inside.

The envelope goes into a bin, and the ballot is given to a bipartisan team that prepares it for tabulation, Portillo said. They open up the ballots, flatten them out and then put them in folders of 200. Those folders are placed into boxes that are used to transport the ballots to tabulation. A custody log tracks each ballot as it moves through the process, Portillo said.

Voting by mail: Duplicating machine

Some mail ballots cannot be read by the electronic readers because they’re either torn or folded too much, Portillo said. In that case, a bipartisan team puts the ballot in a Sentio machine from Runbeck that duplicates the ballot into one that is readable with the exact same information, Portillo said. The original stays with the duplicated ballot, and there’s a sheet that is filled out, designating the original ballot in a certain category, Portillo said.

Tabulation

In the final step, the votes recorded on the paper ballots and flash drives are tabulated using the HiPro high capacity scanner from Dominion.

Every early voting evening, all the mail ballots and flash drives are tabulated. On Election night, everything is tabulated, Portillo said. That’s when results start appearing, she said.

Quashing claims

Some Nevadans with concerns over the state’s election security have pointed to issues in Georgia, where a legal battle is ongoing over whether Dominion voting machines are vulnerable to hacking.

Portillo said she is not sure how other states operate, but she said Nevada uses different software and is legally required to test all of the county’s equipment. Testing is done Clark County election department staff, its cybersecurity team and a bipartisan board from the public.

Not earlier than two weeks before an election and not later than 5 p.m. on the day before the first day of early voting, the county clerk or registrar of voters must test the voting machines to make sure the equipment will correctly count the votes cast for all offices and ballot questions, according to Nevada law.

They’re tested by processing a preaudited group of test ballots that are marked to record a predetermined number of valid votes for each candidate and on each measure, according to Nevada law. The tests must include each office, and some ballots must be marked with excess votes to make sure the voting machine will reject it, according to law.

Then the accuracy certification board and the county registrar of voters certify the tests and sign the necessary reports.

Contact Jessica Hill at jehill@reviewjournal.com. Follow @jess_hillyeah on X.