COMMENTARY: The nation has a health-care crisis, so why limit beds?

Dave Nichols’ life changed in an instant when he fell during a rock-climbing trip in October 2017. A severe brain injury required months of inpatient care. But when his parents tried to bring him home to Oregon, they encountered a problem.

The state did not have enough hospital beds.

Nichols would have to go elsewhere for treatment. His parents looked around and found an opening in Colorado — 1,000 miles away.

As an Oregon state lawmaker, I do not usually focus on health care policy. But I started doing research when Nichols and his mother came to the state Capitol and testified about their experience. What I learned was concerning.

Rather than welcome health care investment, Oregon routinely blocks projects using a regulatory tool called a certificate of need, or “CON.” Before anyone can open or expand facilities, they must prove to the government’s satisfaction that a need exists.

Thirty-eight states — including Nevada — have CON laws or something similar. In all of these jurisdictions, the application process is complex and can take years.

An analysis from the Institute for Justice, a public interest law firm that opposes CON laws, finds 43 requirements and four levels of review in Oregon.

Many smaller investment groups are not even bothered. They cannot afford the cost. Even when they persevere and win state approval, a second hurdle remains: CON laws in 34 jurisdictions, including Oregon, allow existing providers to enter the debate and challenge their would-be rivals.

This is what happened to Post Acute Medical when it applied for a CON to open a 50-bed inpatient rehabilitation hospital in Oregon. After obtaining state approval, an existing rehabilitation facility and the Oregon Health Care Association objected to the application.

Post Acute Medical finally took its money and went elsewhere, citing the “dogged self-interest” of its opponents.

Other would-be investors have faced similar barriers. Encompass Health applied for a CON to open a 50-bed inpatient rehabilitation hospital in Hillsboro, Oregon, but withdrew after spending five years in pursuit of a CON.

NEWCO also tried and failed when it sought a CON for a 100-bed inpatient psychiatric facility in Wilsonville, Oregon.

The roadblocks continue despite chronic bed shortages nationwide. The crisis is especially bad in Oregon, which ranks 49th in the nation for the number of rehabilitation beds per capita. Only Alaska ranks lower. Mental health care and addiction recovery beds are also scarce, and access could decrease as the population ages.

CON advocates say the regulation is necessary to control health care costs by restricting duplicative services, but real-world experience shows otherwise.

California, Texas and 10 other states have operated for years without CON laws. Arizona, Ohio, Indiana and Montana have gutted their CON laws, and North Carolina, South Carolina and West Virginia joined the list in 2023 with significant CON cutbacks.

None of these states reports any negative consequences. The opposite is more likely true. As the Department of Justice concluded in 2004: “Certificate-of-need laws impede the efficient performance of health care markets.”

The ultimate losers are patients, especially those suffering with mental illness, addiction or traumatic injuries. Dave Nichols had resources to seek out-of-state care, but many families in the same situation would be stuck.

My response in Oregon is a bill that received its initial hearing this month. The measure would repeal CON requirements for inpatient psychiatric services, chemical dependency services and rehabilitation services.

Other reforms might be necessary, but these are the most urgent. With the bed shortages that exist, policymakers should be giving the green light to potential investors. Not red tape.

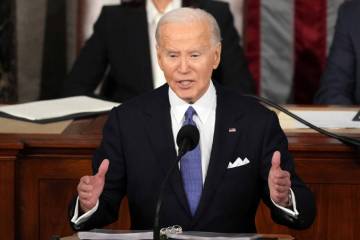

Lucetta Elmer, a Republican, represents Oregon House District 24. She wrote this for InsideSources.com.