Wynn-Okada legal battle highlights once-obscure federal law

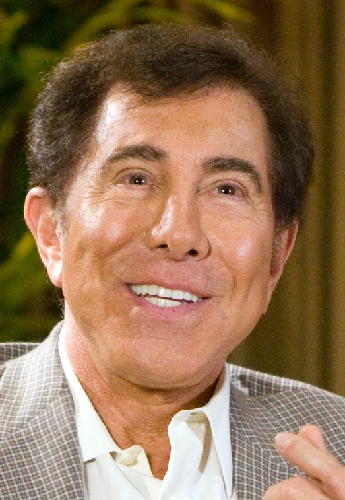

The legal battle between Wynn Resorts Ltd. and Kazuo Okada, the Japanese billionaire who financed the business 12 years ago and recently was ousted as a director and shareholder, is more than just a fight over control of a multibillion- dollar casino company.

It's also about a 1977 law that makes it a crime for U.S. companies or executives associated with them to bribe foreign officials to gain business advantage.

Wynn Resorts and Okada each could face criminal charges or steep fines if continuing federal investigations uncover illegal business dealings in connection with Wynn Macau or Okada's new resort under construction in the Philippines.

With Las Vegas gaming companies maturing into international casino-resort conglomerates, concern about foreign entanglements is higher than ever. With two industry leaders, Wynn Resorts and Las Vegas Sands Corp., now under investigation, executives are learning that doing business according to local custom in some countries can land them in court -- or even prison -- back home.

A once obscure federal law, the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, now looms large in Las Vegas business.

INTERNATIONAL ETHICS

"The Foreign Corrupt Practices Act was an effort to discourage companies from doing unethical things, like paying bribes," said Lawrence J. White, a professor of economics at New York University's Stern School of Business.

Although the law was long on the books, it was seldom enforced. In 2003, for example, not a single person was charged with violating it. But since 2007, 57 companies have paid a combined $4.1 billion to settle corruption charges. Last year, there were 16 corporate cases and 18 new individual defendants, according to the FCPA Digest, published by the New York law firm Shearman & Sterling LLP.

The increase in Foreign Corrupt Practices Act cases, which began during the George W. Bush administration, is often linked to the Sabanes-Oxley Act in 2002, which was passed in reaction to a number of major corporate scandals, including those of the Enron Corp. and WorldCom. Sarbanes-Oxley requires executives to certify annually that they are unaware of any fraud at their companies. Rather than violate Sarbanes-Oxley, many acknowledge violations of the FCPA, which has lead to an increase in federal investigations.

Although the U.S. Department of Justice has had success collecting fines from corporations, its record of prosecuting individuals is mixed.

Of the 93 people charged over the last seven years, 41 pleaded guilty and six were convicted at trial, according to figures Shearman & Sterling compiled. In its report, the law firm found four defendants are fugitives, one was exonerated and three saw their cases dismissed.

The 31 defendants who have been sentenced received an average two years and two months in prison.

The average financial penalty in 2011 was nearly $25 million, the New York City law firm reported.

Michael Czinkota, associate professor of international business and marketing at Georgetown University's McDonough School of Business, said the law has done little to stanch corruption overseas while making it harder for U.S. corporations to compete in places where forms of gratuities are the norm and business executives' careers or a company's earnings are "dependent on delivering the goods."

"The law was originally intended to provide a level playing field for U.S. companies," Czinkota said. "What it has done is put enormous constraints on firms. I teach my students that they'll be better off adhering to it, even though some competitors are not. It doesn't pay to try to be more clever than the lawyers and DOJ."

THE WYNN-OKADA DRAMA

Wynn Resorts' accusations that Okada, with his companies Aruze USA Inc. and Universal Entertainment Corp., violated the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act have brought in the Justice Department and Securities and Exchange Commission to investigate both companies.

Wynn last month released a report prepared by former FBI Director Louis Freeh asserting there is evidence Okada engaged in "prima facie violations" of the act, a conclusion Okada strongly disputes.

The report describes $110,000 in gifts and cash allegedly provided by Okada and his companies to Philippine gaming regulators, and potential benefits of about $5,000 to South Korean officials during visits to Wynn Macau.

Attorneys for Wynn Resorts sued Okada in Nevada state court Feb. 19, alleging a breach of fiduciary duty because his potential violation of U.S. anti-corruption laws could splash back on Wynn Resorts. Because of that, the company invoked a rule allowing it to eject stockholders or directors who might be found unsuitable by regulators.

In a lawsuit filed Monday, Okada's attorneys said federal court is the proper venue for the legal battle because "the issues raised on the face of the complaint involve the resolution of a substantial federal question," whether Okada violated the act.

"Courts recognize that the statutory language of the FCPA is imprecise," Okada's attorneys wrote in their filing. They said it was hard to prove a connection "between the anticipated results of the foreign official's bargained-for action or inaction and the assistance provided by or expected from those results in helping the briber to obtain or retain business."

But Wynn's shot at Okada was actually the second attempt to bring the act to bear in what had been a long, quiet boardroom battle. In January, Okada went public by suing Wynn Resorts to gain access to records relating to the company's $135 million donation to the University of Macau Development Foundation. Okada has called the donation suspicious, though he has not said why he considers it so. It's notable, however, that Wynn Resorts made the donation as it waits for Chinese government approval to build a new major hotel-casino on the Cotai Strip.

Wynn Resorts disclosed that the SEC has asked the company to preserve its records related to the donation as part of an informal inquiry.

CALLS FOR CLARITY

Wynn Resorts isn't alone in dealing with an Foreign Corrupt Practices Act investigation. Las Vegas Sands disclosed in its 2011 annual report that it was subpoenaed by the SEC for documents regarding the company's compliance with the law. It has also disclosed that the Justice Department is conducting a similar investigation The company, run by Sheldon Adelson, has major hotel-casinos in Macau and Singapore.

Las Vegas Sands said it believes the subpoena stemmed from allegations in a wrongful termination lawsuit brought by its former head of Macau operations, Steve Jacobs. Jacobs has claimed that Adelson pushed him to illegally retain the services of an elected Macau official.

Okada's filing in U.S. District Court came one day after the American Gaming Association joined with the U.S. Chamber of Commerce to ask the Justice Department and SEC to "clarify the law" and offer better guidance to businesses.

One big issue is how U.S. companies can do business in markets where there's little or no separation between government and industry.

An analysis of FCPA violations in 2011 shows they're most common in markets in which major industries are dominated by state-owned or state-controlled businesses. Most happened in 11 Asian countries, including India, Indonesia, South Korea and Vietnam, according to the FCPA Digest.

U.S. Chamber of Commerce Senior Vice President Harold Kim said clarification of act's enforcement practices is needed. He said most companies are concerned about who qualifies as a foreign official under the law, a definition that includes not only traditional government officials, but also "employees of state-owned or state controlled" entities that are more like businesses.

And what kind of conduct crosses the line? Is buying lunch for a low-paid government official on par with slipping him an envelope stuffed with cash?

Kim said a company recently sponsored a medical convention in Asia, which included attendees from government-run medical facilities. When a storm made it difficult for attendees to get home or to reach other hotels, he said, the company, which he declined to identify, gave a government official a few dollars to take the subway home.

Kim said the company asked whether the subway fare should be reported as a gift to a foreign official.

His advice: better to report it.

"The reach (of the FCPA) is so vast it touches every industry in the U.S. economy," Kim said. "It certainly has a chilling effect for companies that want to do business overseas. It has stopped some of them from doing business overseas."

far-reaching effects

Although the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act is an entirely American law, it ensnares even foreign companies that violate its provisions far from the United States. That's because its provisions cover any company from anywhere if its stock is listed on a U.S. exchange.

Thus one of the largest FCPA cases to date involves Siemens AG, the massive German manufacturing and engineering conglomerate that has 360,000 employees in 140 nations and operates 285 manufacturing plants around the globe.

In 2008 Siemens was accused of bribing officials in a number of countries where it does business, but not in the United States. But the company still was charged in the United States, and eventually paid $1.6 billion to U.S. and German regulators to settle the case.

Individual criminal charges are still pending against eight former Siemens executives and contractors who were indicted in the United States in December. The eight are accused of paying $100 million to high-level Argentine officials to win a $1 billion contract to make national identity cards.

Although none of those alleged illegal acts happened in the United States, the German company's activities in Argentina still fall under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Department of Justice because Siemens securities are traded here.

Exactly what impact the prosecutions will have on global business practices remains unclear.

Czinkota said the case against Siemens has had a "cold water affect on German firms" doing business overseas.

Meanwhile, the World Bank estimates that government officials worldwide collect $1 trillion in bribes each year.

Contact reporter Chris Sieroty at csieroty@reviewjournal.com or 702-477-3893.