Meet seven African-Americans who helped shape Southern Nevada

F or even the most recent newcomer, it’s no secret that Nevada is a fascinating place whose history was forged by some pretty fascinating people.

Nevada schoolchildren meet some of these fascinating characters through their Nevada history classes. It’s more difficult for adults.

To cap off this year’s observance of Black History Month and as part of the ongoing celebration of Nevada’s 150th birthday, we asked a few history experts to name African-Americans from Southern Nevada’s history with whom today’s Nevadans should be familiar.

Our roster represents a thin slice of the historical pie. For more information, visit “Documenting the African American Experience in Las Vegas” (digital.library.unlv.edu/aae), an online exhibit created by UNLV’s University Libraries.

WALTER MASON

Walter Mason has spent his entire career in the entertainment industry as an actor, director and producer. During the late 1980s and 1990s, Mason also became one of the first African-American entertainment directors of a Las Vegas Strip hotel.

Mason was born in Detroit and earned a bachelor’s degree in theater from Wayne State University. His theater credits include lead and award-winning performances in “Othello,” “The Tempest,” “A Raisin in the Sun,” “The Yearling,” “Golden Boy” and “A Streetcar Named Desire.”

He also has produced and hosted radio shows and TV productions, worked with such talents as Alvin Ailey and James Earl Jones, served as an associate to the dean of the Yale University drama school, worked with stars such as Frank Sinatra and Ella Fitzgerald, and spent several years as Sammy Davis Jr.’s production manager.

In August 1986, Mason moved to Las Vegas to work as an entertainment executive at the then-Las Vegas Hilton (now the LVH). There, Mason says, “I was responsible for bringing (in) such entertainers as The Four Tops, The Temptations and Sarah Vaughan, as well as such acts as Wayne Newton, of course.”

“When I began, I was coordinator of entertainment, then, later, entertainment director. My last title was director of entertainment services,” he says. “It was very enjoyable, because you felt you were doing something that made a difference in the entertainment business.”

Did he, perhaps, book African-American acts that might not have been booked otherwise? “I hoped that was the case,” Mason says.

Now retired, Mason, 88, founded the nonprofit Ira Aldridge Theatre Company and devotes much of his time and expertise to working with youths at the West Las Vegas Arts Center.

“I’ve found if you ignite the thoughts and ideals of people of a younger age, they can be prepared to get in the theater,” he says. And, by fostering a love of the arts when children are young, he adds, “they can turn into some very auspicious people to offer something to the community, something to the arts and something to the world.”

HATTIE CANTY

Hattie Canty grew up in Alabama before moving to California, marrying and starting a family, according to Claytee White, director of the Oral History Research Center at UNLV Libraries.

Then, during the 1960s, Canty and her family moved to Las Vegas, where Canty found work as a maid for the Thunderbird Hotel and, after the death of her husband, the Maxim hotel.

According to White, it was after her husband died that Canty learned firsthand about the value of belonging to a union, which was able to provide her with health benefits and a pension.

As a new member of the Culinary Union, Canty “walked picket lines on her days off,” White says. “She became more active after being informed that six hotels did not have union representation. Over the years, she became involved in securing better salaries for women and increasing the number of African-Americans in high-paying positions in the casino industry.”

In May 1990, Canty became the first black president of Culinary Union Local 226 and, White notes, was re-elected by landslide margins in 1993 and 1996.

“During her tenure, she had her share of labor challenges,” White adds. “She went to jail at least six times while striking. She influenced contract negotiations for the downtown hotels, improved race relations among workers and involved more members in union operations.

“However, the crowning glory of Hattie’s work was implementing the Culinary Training School that allows training in most union job categories.”

Canty died in 2012. But, White notes, “thanks to the Culinary Union Local 226, Hattie Canty is living proof that a maid can travel, own a home and send her children to college.”

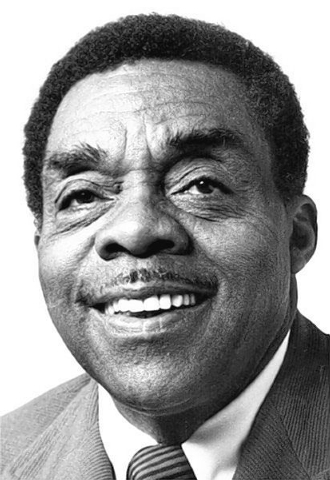

JIMMY GAY

Jimmy Gay was born in Fordyce, Ark., and, after college, studied embalming science in Chicago, White says.

Then, in 1946, Gay and his wife, Hazel, left Arkansas and came to Las Vegas, where Gay became Las Vegas’ first African-American mortician.

In 1958, Gay was appointed by Gov. Grant Sawyer to serve as the first African-American member of the Nevada Athletic Commission. He also would become a casino and hotel executive — at properties that include the Sands and Union Plaza hotels — when that still was unusual for an African-American man.

In 1988, Gay was awarded an honorary degree from UNLV. He died in 1999.

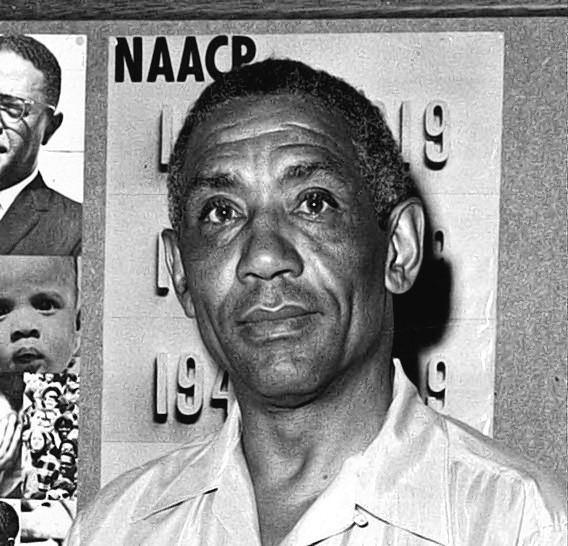

CHARLES KELLAR

History remembers Charles Kellar as the first African-American to pass the Nevada State Bar exam, in 1960. But history also remembers that Kellar didn’t become the state’s first black lawyer.

In fact, White says, “his license was awarded in 1965, and while he was waiting, two other black attorneys were passed by the bar.”

Kellar, a native of Barbados, moved to Brooklyn, N. Y., with his family as a child. He became an attorney in New York — his practice included civil rights law — and moved to Las Vegas in 1959. After a year of establishing residency, Kellar sat for the bar exam, White says.

But, she continues, “they said, ‘This score is too high. He must have cheated.’

“He had to fight for five years, and during that time he worked at a lot of things. He studied for his real estate license and he worked closely with the NAACP here and in Reno.”

White notes that Kellar was sent to Nevada by Thurgood Marshall, then an NAACP officer, as part of an effort to “make sure there were black attorneys in every state. They were trying to get legal representation in all states.”

To put it another way, says Michael Green, a history professor at the College of Southern Nevada, Kellar “was an attorney sent here by the NAACP to shake things up, and he shook things up.”

Among his achievements here, Kellar “filed the lawsuit that ultimately led to school integration,” Green says, and Kellar “played an important role in the 1971 consent decree that led to more African-Americans being hired in casinos for front-end jobs.”

Kellar died in 2002.

“Just generally speaking, and I say this with great affection, (he was) a bull who carried his own china shop,” Green says. “If there was a battle going on about civil rights, he was in the middle of it.”

ALICE KEY

Alice Key was “a renaissance woman,” White notes — a dancer, writer, community activist, a state deputy labor commissioner who counted such lights as Joe Louis, Lena Horne and Paul Robeson among her close friends.

According to White, Key — a Kentucky native who as a child moved to California with her family — left Riverside, Calif., on the day of her high school graduation and moved to Los Angeles, where she enrolled in journalism classes at UCLA. Fascinated by the entertainment business, she became a chorus line dancer at the Cotton Club in Culver City “where the line of dancers was all black and the audience was all white.”

When Key’s dancing career ended in 1943, she became a newspaper reporter first in Los Angeles and, after moving to Las Vegas, at the Las Vegas Voice, the community’s black newspaper.

Also after moving here in 1954, she became active in the civil rights movement. Combining her journalism and her entertainment expertise, as well as her interest in culture and politics, Key and fellow civil rights pioneer William H. “Bob” Bailey created “Talk of the Town,” Nevada’s first all-black TV show.

Key also worked with the NAACP here and was appointed deputy state labor commissioner. It was, Green notes, “not a period when you saw a lot of African-American women, or women, for that matter, in such prominent positions in media or government.”

DR. CHARLES WEST

Many prominent African-American figures worked to advance the cause of civil rights in Southern Nevada. And, among them, Green says, Dr. Charles West is “someone who doesn’t get as much attention, I think, as he should.”

According to Green, West helped to lay the groundwork for successive generations of civil rights activists in the valley, working with other notable civil rights activists such as Dr. James McMillan and William H. “Bob” Bailey.

West came to Southern Nevada in 1954, becoming Las Vegas’ first African-American medical doctor, Green says. “In the era of segregation, he would make house calls on the Strip and get paid in chips, which was not that unusual for doctors of that time if you made house calls on the Strip.”

West also became active in the civil rights movement here, often working behind the scenes, White says. Among other things, Green adds, West helped “to get the ball rolling” for such landmark civil rights advances as the Moulin Rouge agreement, forged in 1960, to desegregate casinos on the Strip.

West also founded and published the Las Vegas Voice, which served the valley’s African-American community and which was, White says, the only black newspaper in the state.

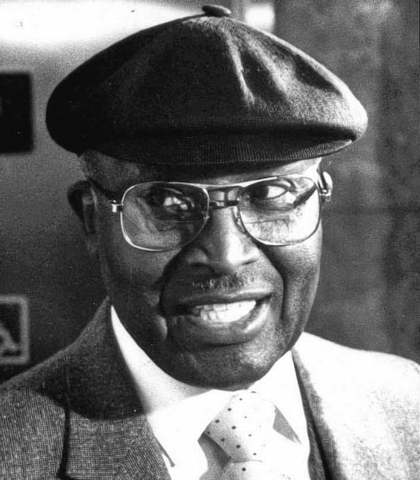

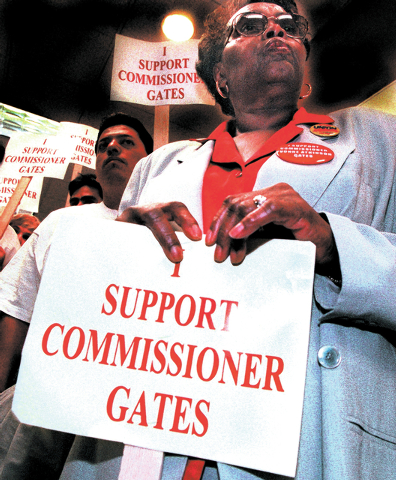

WOODROW WILSON

Woodrow Wilson was born in Mississippi and moved to Southern Nevada during the 1940s to work at Basic Magnesium Inc. in Henderson, White says.

Among Wilson’s accomplishments here was creating the West Side Federal Credit Union, the first local financial institution to serve the African-American community, in 1951. In 1966, Wilson was elected to the Nevada State Assembly, becoming the Assembly’s first African-American member, and was re-elected to that body in 1968 and 1970. His accomplishments there included introducing a state fair housing law. In 1979, Wilson was appointed to the state’s Equal Rights Commission.

Wilson became a Clark County commissioner in 1980, but he resigned four years later after becoming embroiled in an FBI bribery sting. He pleaded guilty to a charge of attempted extortion. He died in 1999.

Contact reporter John Przybys at jprzybys@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0280.