Animal hoarding: People are hostages, too

Animals aren’t the only hostages when it comes to hoarding.

The critters and their keepers are victims of a compulsion that creates a heartbreaking cycle for all involved, including family, friends, neighbors and often the community as a whole, according to Carolyn Rodriguez, director of the Hoarding Disorders Research Program at Columbia University in New York.

“I sort of think of it as a case where love is not enough,” Rodriguez said. “(Hoarders) don’t realize what they are doing is not right — even in the face of evidence in the contrary.”

Although hoarding was recently defined as a distinct disorder, animal hoarding still isn’t classified as a mental illness.

The reason? Researchers just don’t know enough.

Until the mid-1990s there just weren’t studies on animal hoarders, Rodriguez said. Now, there are fledgling research efforts and even a reality show, as instances of people acquiring animals in the double and triple digits pop up.

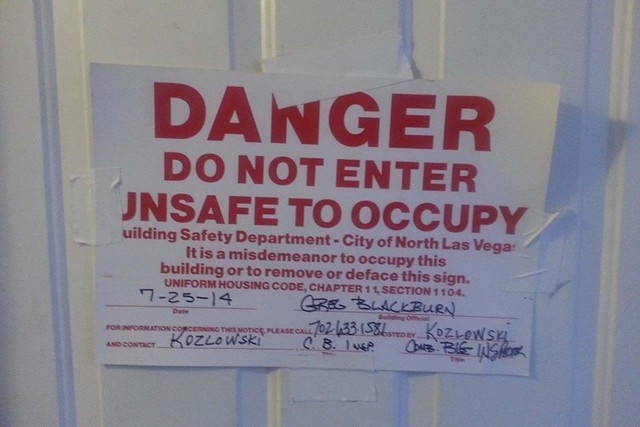

In the past four months, the Las Vegas Valley has had three animal hoarding cases. Last month, the city of Las Vegas had to relocate a cat hoarder and spend $10,236 to clean her home. The city put a lien on the property to recoup funds.

In the wake of the most recent case, which was uncovered after a fire left 41 dogs dead, animal activists want lawmakers to take action.

Animal hoarding is a complex problem for the variety of government agencies that become involved, such as the health district, code enforcement, animal control, social services and prosecutors.

“It’s important for people to understand that these are very difficult cases by the very nature of the problem — that it is oftentimes within someone’s private home. You’re dealing with personality issues, you’re dealing with people that might be quite sensitive and vulnerable,” Southern Nevada Health District spokesman Andy Chaney said. “Anytime you are dealing with an issue like this, it’s difficult because you are dealing with somebody who quite possibly is having trouble dealing with their situation in the world.”

Finding people who need help can also be a challenge.

The public was unaware of the most recent hoarding incident in North Las Vegas until tragedy struck. Animal control was in the process of checking out a tip — which only came after a relative broke down and made a call.

Hoarders often end up isolated, and it’s difficult for family and friends to watch a loved one live in such a state, Rodriguez said.

Animal activists expressed outrage over the fact that North Las Vegas animal control had visited the home that housed almost 100 dogs days just before a fire killed dozens of them.

“The challenge, really, is that there is no regulation. We don’t regulate people inside their homes,” Chaney said. “One of the main things we have to do is be sensitive to the people we are addressing. We are coming into their home and we are trying to get them help.”

North Las Vegas police Sgt. Chrissie Coon has said just barging into someone’s home based on an anonymous tip when there is no visual evidence on the outside of the home is a civil rights violation.

In the most recent North Las Vegas hoarding case, animal activists have been calling for felony animal cruelty charges — which could mean years behind bars.

To charge animal cruelty, prosecutors must show the animals were abused, Coon said. Sometimes a person might have an excessive number of animals — a lesser charge — but if there isn’t proof the animals were suffering, the cruelty charge won’t stick.

State Sen. David Parks, D-Las Vegas, said after being approached by Nevada Voters for Animals, which championed the bill that increased penalties for certain acts of animal cruelty in Nevada, he is researching how to craft legislation to address animal hoarding.

It’s too early to talk specifics, he said, but noted he is being careful to make sure the bill wouldn’t restrict a person’s civil liberties.

“Sometimes we feel like we need to pass some legislation that makes us feel good,” Parks said. “I’m not looking for a piece of legislation that is a solution to a nonexistent problem. I think we are beginning to see we definitely have problems.”

Illinois and Hawaii are the only states with language on the books addressing animal hoarding, but Hawaii is the only state that has specifically made animal hoarding a crime, according to the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. In Hawaii, it’s a misdemeanor. One complaint animal activists have about Hawaii’s law is that it doesn’t mandate any sort of counseling.

Although Illinois’ Humane Care of Animals Act doesn’t make animal hoarding a crime, it specifically defines animal hoarding. It requires someone who is convicted under the act who fits the hoarder definition to undergo an evaluation and whatever treatment is deemed appropriate.

Rodriguez said communities have seen success using task forces that can help sort out the best approach in individual hoarding cases. Orange County, Calif., has a volunteer advisory group that meets monthly to look at current hoarding instances, according to its website.

Rodriguez said she understands the outrage people feel when pet hoarding comes to light, but prison time is unlikely to help hoarding.

Animal hoarding tends to suggest severe mental illness, she said.

“It’s a big problem. An understudied problem,” she said.

Many times, the hoarder will let their own health spiral out of control to care for the animals, she said.

Steve Maltz said his brother Eric, who was the renter involved in the most recent North Las Vegas hoarding case, would often go without food to feed his dogs. Hearing the public accuse his brother of animal cruelty was difficult for Steve Maltz.

“This guy loved his animals more than he loved humans,” said Maltz, who didn’t approve of his brother’s hoarding. “They are trying to portray him as an evil person.”

Maltz said his brother would pick up strays in hopes of saving them from being euthanized at a shelter. The situation spun out of control.

It’s a sad story typical of animal hoarding, according to Rodriguez.

“The animals themselves are prisoners — in the sense that they are in this environment of neglect and filth — and individuals,” Rodriguez said. “(Hoarders) do want to take care of these animals, but they are misguided.”