Yo-yos, kickstands and monkey paws: How slot cheats stole big and landed in ‘Black Book’

The names of the devices are as colorful as the people who used them.

Monkey paw. Kickstand. Yo-yo.

These are some of the cheating devices criminals brought to Nevada casinos to trick slot machines into producing unwarranted payouts.

And those who used them were often arrested and convicted, but when they were released from incarceration, they became prime candidates for nomination to Nevada’s List of Excluded Persons, known as the “Black Book.”

James Taylor, a retired Nevada Gaming Control Board Enforcement Division chief, spent much of his career confiscating the devices and learning how they worked so he could advise casinos on what they could do to prevent being bilked out of millions of dollars. Some of the most notorious cheats scored millions in illegal jackpots before they were caught.

Most of the devices he collected have been donated to the National Museum of Organized Crime and Law Enforcement — the Mob Museum — in downtown Las Vegas.

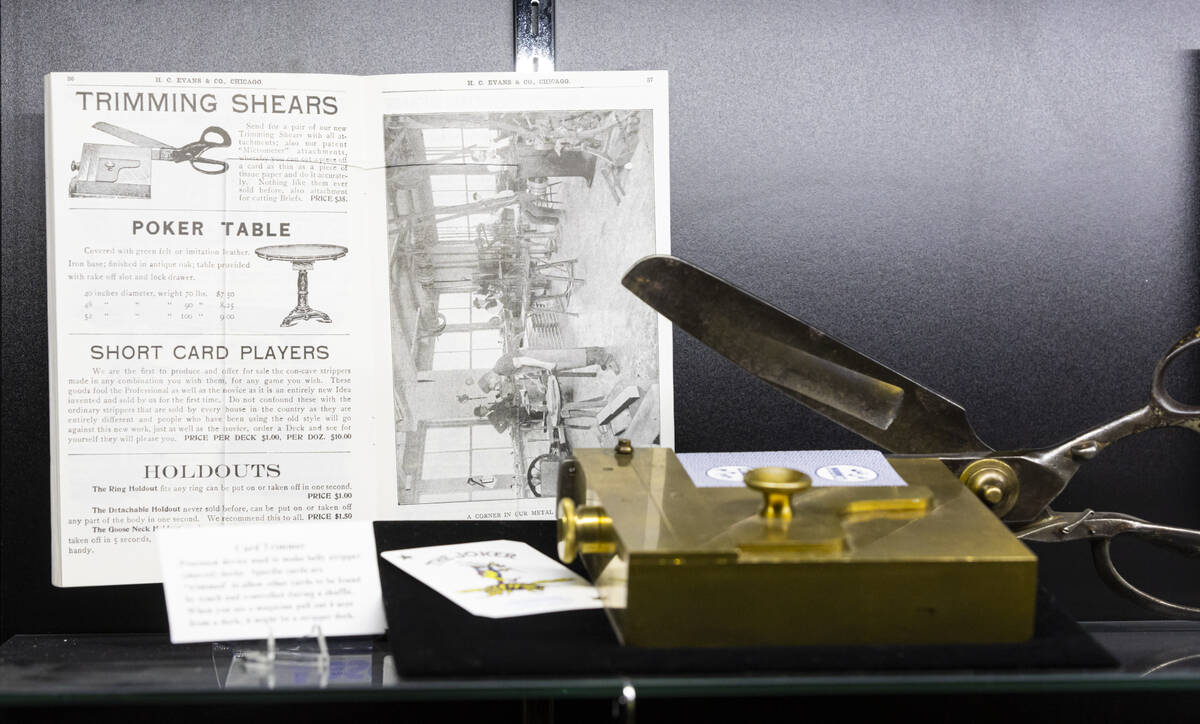

Types of cheating devices

Many of the devices confiscated were popular when casino players inserted coins into slot machines. As manufacturers updated their machines and made them coinless, they had to protect them in different ways to prevent thefts with devices that would trick bill validators.

The simplest form of cheating initially came from people using the same methods they had for getting a free soda from a vending machine — slugs.

But Taylor’s first criminal arrest came in 1995 of individuals using monkey paws and yo-yos.

“The simplest yo-yos, which we also called stringers, involved attaching a string to a quarter and sending it down the chute,” Taylor said in an interview.

Cheats also would come into the casino with a small object the size of a cigarette lighter.

“We’d consider this a coin-in device. The thing that looks like a cigarette lighter had nothing to do with the cheating part,” he said. “It would have tape wrapped around it because tape would come off, and having a roll of tape in the casino looked a little suspicious.”

The user would tape string to a quarter, insert the coin and bounce it up and down, hence the name yo-yo. The coin would move past a sensor and register a credit on the machine.

Some yo-yos were slightly more sophisticated with a hole drilled into the coin with the string tied to it.

Slot machine manufacturers caught on to yo-yos and designed coin slots with rotating blades that coins would pass through to activate credits.

But Taylor said the cheats also became more creative and found new ways to defeat the machines.

One of those devices was the monkey paw, a flat piece of metal with a bendable rod that would be used to hook around a lever inside the machine.

“Once you got it in place, you could wrap it around to hold a lever open to add credits,” he said.

Another device used to score illegal payouts was the kickstand, which was used to enter the machine from the hopper instead of the coin slot. It, too, was used to trick the machine into activating multiple credits at a time.

“How the wire was bent would depend on the type of machine, so there are about 50 different versions depending on what kind of machine they were going to hit,” Taylor said. “Instead of getting 10 credits, they’d get 100. But because some of the machines had a time-out feature, they couldn’t just hold it open and get 1,000 at a time.”

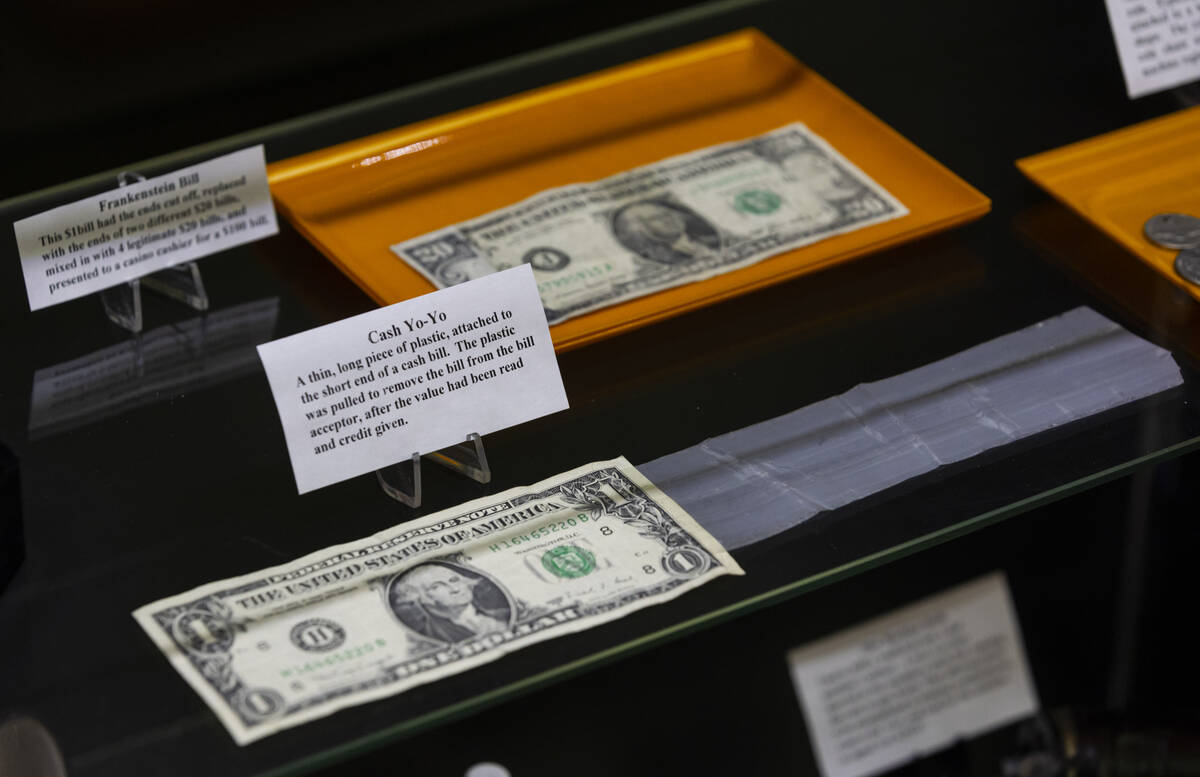

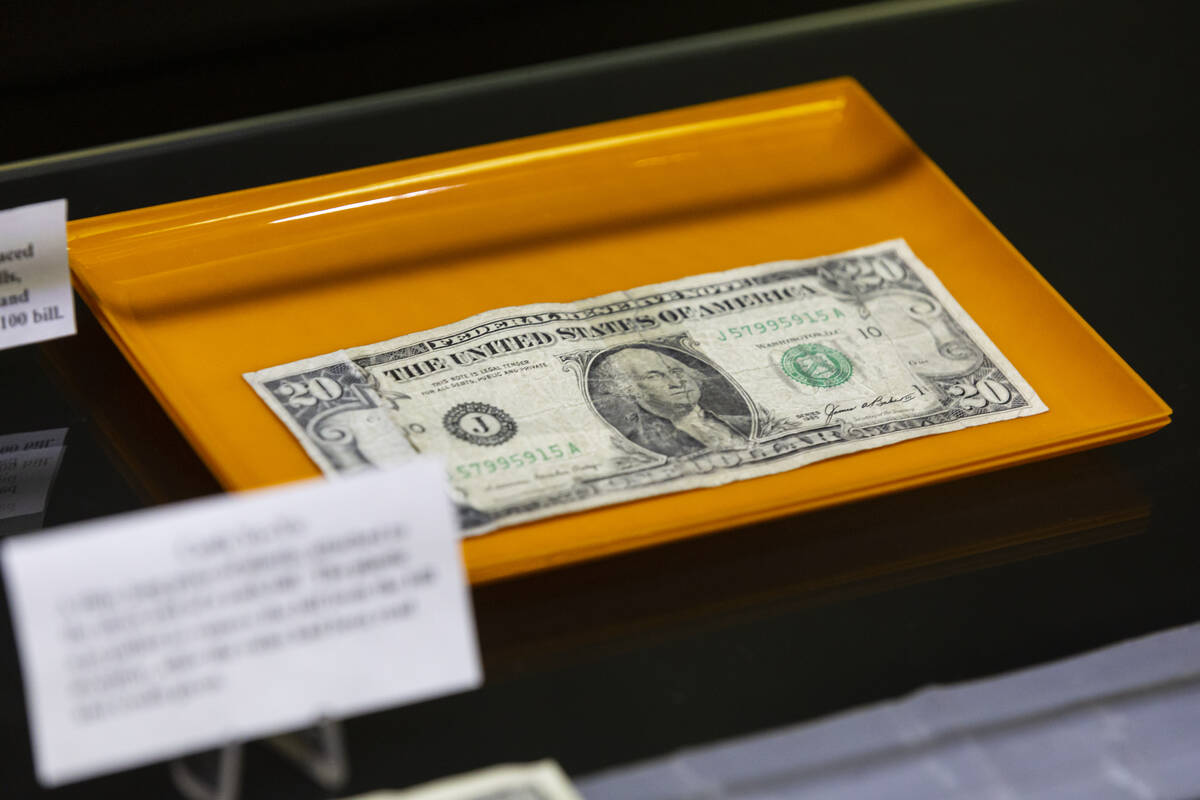

Once slot machines became coinless, thieves’ technology evolved and they came up with ways to trick a bill validator into adding more credits than the amount of the bills inserted.

One such tool was an optic device that lit up inside the machine and essentially blinded the bill validator, enabling the bad guy to add credits.

Thieves were caught when the amount of money in the machine didn’t match the amount of credits played. Investigators would review video surveillance to find the perpetrator, and it was only a matter of time before they would track down the thief who went from machine to machine and casino to casino to attempt to repeat the successful operation.

Notorious slot cheats

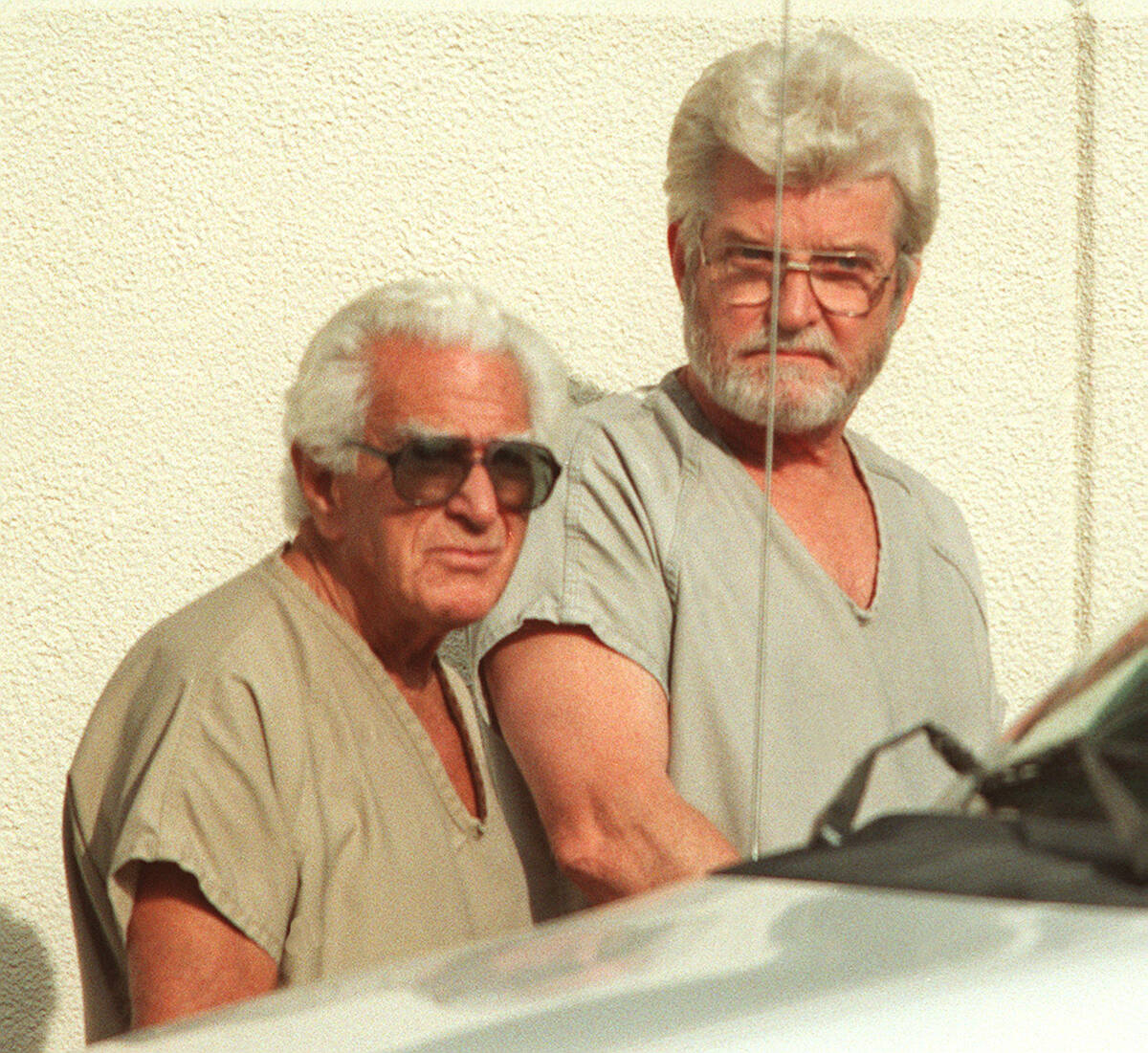

Among the most notorious slot cheats who landed in the Black Book was Dennis Nikrasch, who was inducted under one of his aliases, Dennis McAndrew, on Sept. 24, 2004, and removed June 8, 2011, a year after his death.

Nikrasch was believed to have stolen $16 million over 22 years.

Taylor considered him a genius. A locksmith connected to the Chicago mob, Nikrasch was meticulous in his planning and figured out a way to re-engineer new computer code into a slot machine to produce a winning spin. What baffled Control Board agents was that after he manipulated a machine, there was no trace of the machine having been changed.

To introduce new codes without being detected, he hired a crew of “blockers” to stand in the way of surveillance cameras while he broke into and changed machines. That was also tricky because an alarm goes off seconds after a machine has an unauthorized opening.

Among his crew members over the years were Eugene Bulgarino, who was inducted the same day as Nikrasch, as well as a crew of other people who also landed in the book, including John and Sandra Vaccaro – the only woman currently listed. The Vaccaros were added in 1986, and John Vaccaro was removed in 2016 after his death. Sandra Vaccaro today is believed to be 85 and a resident of Henderson.

Nikrasch’s biggest score came on a Wheel of Fortune machine from which he stole $3.7 million. Control Board agents working with the FBI were able to wiretap Nikrasch’s home, and agents were tipped that the Nickrasch crew was targeting a $10 million Megabucks jackpot.

Agents debated whether to try to catch Nikrasch in the act or to bust him ahead of the score, eventually deciding that it would be a bad look to allow him a theft opportunity.

When agents moved in on his house, a search warrant was executed and all of the Nikrasch cheating devices were discovered in a workshop in his home.

Agents found slot machine and bill validator parts throughout the house. Agents determined he had started a cottage industry by selling cheating devices to other criminals.

When he was apprehended, authorities offered Nikrasch a plea deal of lesser prison time in exchange for explaining how his devices worked.

Staying loyal to his criminal roots, he opted for the longer term and took his secrets of how his devices worked to his grave.

Contact Richard N. Velotta at rvelotta@reviewjournal.com or 702-477-3893. Follow @RickVelotta on X.