Nevada law enforcement agencies profit from forfeiture cases

After 28-year-old Anthony Garcia died in July in a rollover crash near Primm, Las Vegas police found about $26,000 in a duffel bag near his body, along with two Mason jars containing 64 pounds of THC hash oil.

That money was seized by police and is currently held up in a pending civil asset forfeiture lawsuit, according to court records, but Garcia’s family is named as a possible claimant in the case.

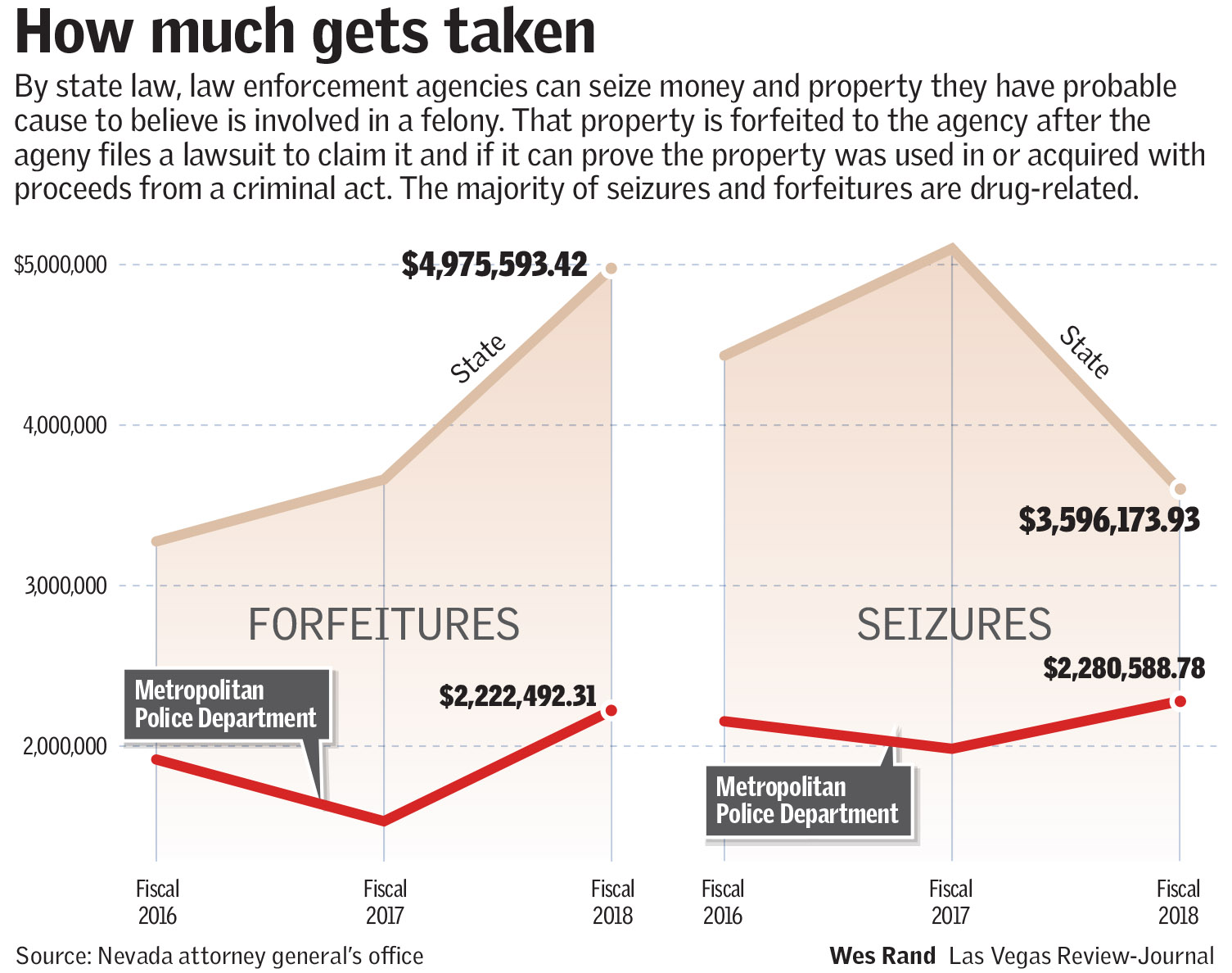

The Metropolitan Police Department seized about $2.3 million in property, including cash, during the fiscal year that ended in July and took in about $2.2 million in civil asset forfeitures, according to the Nevada attorney general’s annual forfeiture report.

On top of that, local law enforcement agencies that aid federal agencies in seizures can get a cut under the Federal Equitable Sharing Program. Metro received about $64,000 in forfeiture money from the U.S. government last fiscal year.

A contentious issue

A 2017 study by the Nevada Policy Research Institute found that seizures and forfeitures “disproportionately target neighborhoods with relatively high levels of minorities and low-income residents.”

According to the report, 66 percent of forfeitures in 2016 occurred in 12 of Las Vegas’ 48 zip codes. The average poverty level in those zip codes was 27 percent, compared with the 12 percent rate in the others. In those most-targeted zip codes, the average non-white population was 42 percent. The non-white populations of the other zip codes was 36 percent.

“Because a majority of forfeitures concern less than $1,000, there is often no practical recourse for the alleged lawbreakers,” the report states.

This is because the cost of hiring an attorney and pursuing legal action would be more than the amount seized.

“It’s a very abusive sort of system,” Las Vegas attorney Tom Pitaro said. Often his clients are not notified when their vehicles are cleared and ready to be picked up, he said, so they rack up fees for storage.

Pitaro said he represented a client whose Mercedes was seized and not returned for almost 10 years.

“They lost track of it,” the attorney said. “They put it in a lot somewhere, and when he got it back, there were weeds growing out of the engine block.”

Pitaro said the client eventually sued for the value of the car. He said many other clients have had issues getting their property back after it has been seized for evidence or forfeiture.

“It’s a pain in the neck, is what it is,” he said. “The process is very bureaucratically inept.”

Metro’s chief financial officer, Richard Hoggan, said seizures and forfeitures are meant to be punitive.

“Our paramount issue is that people involved in criminal activity not reap rewards from that activity,” Hoggan said.

The majority of seized money comes from people accused of drug-related crimes, he said. “We say, ‘This guy did something really bad, and he shouldn’t get paid for dealing drugs or pimping teenage girls.’ ”

On Feb. 20 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of an Indiana man whose Land Rover SUV was forfeited after he pleaded guilty to dealing in a controlled substance and conspiracy to commit theft. The man paid about $42,000 for the SUV with money he had inherited, but the maximum fine for his drug charge was $10,000.

“The question was whether or not the Eighth Amendment provision that protects against excessive fines applies to the states,” UNLV professor Ian Bartrum said. Bartrum teaches constitutional law and theory at the Boyd School of Law.

The court ruled that the amendment’s excessive fines clause did apply to the case, Bartrum said.

But the Nevada Supreme Court already made that distinction in Levingston v. Washoe County in 1998, after a Reno home owned by a man’s four heirs was seized on suspicion of illegal drug activity. The court ruled that the forfeiture of the home would constitute an excessive fine under the Eighth Amendment and turned it back over to the heirs.

Seizures and forfeitures

Police seize money and property that they have probable cause to believe are the proceeds of or were used in commission of a felony, like drug trafficking, murder or fraud.

Under state law, police can seize property without a warrant if it is found during an arrest, inspection or the execution of a search warrant, or if there is “probable cause to believe the property is subject to forfeiture.”

“Just because something’s been seized doesn’t mean it’s forfeited,” Metro Assistant General Counsel Matthew Christian said. “We don’t just take it. Once it’s been seized there has to be a legal filing that results in a court order for forfeiture.”

Metro’s legal counsel files a suit against the property in District Court and must identify possible claimants to the property through “reasonable diligence,” according to the law.

As of Friday, nearly $600,000 in cash and eight vehicles are wrapped up in pending civil forfeiture cases filed during the current fiscal year, including six pickup trucks tied to a bust involving credit card fraud.

Claimants are allowed to join the lawsuit and explain their circumstances to Metro, Christian said, and if it is determined that the money was not involved in a crime, it is returned to them within seven days.

Christian said an example might be a man arrested on drug charges who had $1,000 that his mother gave him to make a car payment. Even if the man were convicted of the charges, he could join the forfeiture proceeding and explain the circumstances.

In that case, Metro would speak to his mother to confirm the man’s claim and then return the money to her, Christian said.

“And we’ve seen this before, where it’s money won through gambling and things like that,” he said. “We had one where it was birthday money.”

The same goes for vehicles and houses that were used in crimes without the owner’s knowledge or consent, which is called the “innocent owner defense,” he said.

In every suit, the burden is on Metro to prove that the money or property was involved in a crime.

Police can seize anything they believe is involved in a criminal offense, including drugs and drug paraphernalia, vehicles, houses and mobile homes. The majority of seizures involve cash.

In one forfeiture from the last fiscal year, Metro received golf balls and a pair of binoculars.

Metro spokesman Aden Ocampo Gomez said the items were seized after police stopped a man driving a stolen car filled with stolen items. Items in the vehicle belonged to at least 13 different people, including the suspect, Ocampo Gomez said.

The owner of the balls and binoculars was never identified, so the property was forfeited.

Money goes to victims first

Money and property forfeited to Metro are used for restitution first. Christian said that in one fraud case, a woman persuaded an elderly man to sign his condo over to her. By filing a forfeiture suit and placing a lien against the condo, Metro prevented the woman from selling it and pocketing the money before she went to trial. The condo was returned to the man who was defrauded.

“It can be used to ensure that a victim of crime is made whole,” Hoggan said.

Sometimes funds can be seized directly from suspects’ bank accounts. Police took nearly $8,500 from former Henderson Constable Earl Mitchell, who was accused of using $163,000 of public money for personal purchases and a “gambling lifestyle.”

Next, Metro pays the expenses associated with forfeiture, such as vehicle towing and storage, legal costs and staff salaries, Hoggan said. Some is shared with other agencies.

Metro can keep the first $100,000 generated by forfeitures but must give 70 percent of the remaining balance to the Clark County School District. That money must be used to buy books and computer hardware and software, according to state law.

Of the $2.2 million forfeited last fiscal year, the school district received just under $1 million and Metro received about $500,000, after expenses.

Forfeited money from drug crimes must be used for narcotics enforcement, and the remainder must go into a special account, rather than Metro’s general fund. The money can’t be used for day-to-day operating expenses.

Metro is using a $3 million cut from a 2017 FBI crackdown on a casino-based money laundering scheme to offset the cost of a new firearm training center.

Over the last three years, forfeiture funds have been used to buy narcotics test kits, as well as robots and other equipment for SWAT, according to documents provided by Hoggan. The funds also paid for two K-9 units — one that detects firearms and another that sniffs out drugs.

“We don’t plan on those funds,” Hoggan said. “If they come and we can use them for the public good, then we do.”

Contact Max Michor at mmichor@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0365. Follow @MaxMichor on Twitter.