Las Vegas shooting survivor shares insights in high school essay

It started with an open-ended prompt in English 12. Write a persuasive or argumentative essay.

Tari Hawks went over with her 37 seniors at Desert Oasis High School what to incorporate into their essays: pathos, logos, ethos, how to persuade. But the topic was open.

Jake Schmidt didn’t plan on writing about what he did on Oct. 1. But in the days after he escaped gunfire at the Route 91 Harvest festival, the essay was the only assignment he could sit down and do that week.

“I detest these allegations that state that we should lose hope and give up on humanity,” he wrote. “There are always going to be bad people, there are bad apples in every bushel, despite that, there will always be more good in this world than bad.”

With 58 killed and more than 500 injured, and the lives of some 22,000 people shaken, the 18-year-old tried to make sense of the unspeakable.

The thin, blue-eyed high school senior wrote about the blood on the ground. The people limping with bullets in their legs. People running for their lives toward the exits.

He wrote about the security guards, the police officers, the firefighters, the emergency medical technicians and other “random people willing to run towards the gunfire to protect people they have never met.”

He wrote about the good Samaritans using the shirts off their backs as tourniquets, the people lying on top of loved ones, taking bullets for them, and his personal trainer who ran back into the venue, carrying bodies and piling them into truck beds “with the hopes of saving just one of those people.”

By the end of the night, the man was wearing only his shoes, pants and hat. He had used everything else to stop others from bleeding.

A friend of Schmidt’s family was shot in the leg as she was running out, and a man picked her up and threw her in a cab, he wrote. Another girl he knows, Rylie Golgart, was shot in the back, and two off-duty firefighters placed her on a backboard.

“Both of these girls credit them being alive to these selfless human beings who put their safety on the back burner to help them,” he wrote in the essay.

Schmidt was also touched by the scores of people lining up at blood drives despite six- to eight-hour waits, the nearly $11 million raised through a GoFundMe account started by Clark County Commission Chairman Steve Sisolak and Clark County Sheriff Joe Lombardo, and the individual donations for the victims on the road to recovery.

“It’s easy to look at this moment and say, ‘These type of evil actions, such as the one this man carried out, are the reason that I have lost faith in humanity,’ But I refuse to believe this,” Schmidt wrote. “The day I lose my faith in humanity will be the day that people stop running towards the gunfire, it’ll be the day that people are no longer laying on top of one another to save them from the flying bullets, it’ll be the day that these strangers watch someone else’s daughter, sister, girlfriends, mom or wife die without the intention of helping them.”

Country boy in Vegas

Schmidt was born listening to country music. Until he was 3, he and his family lived in Silverton, Oregon. He grew up hunting in Northern Nevada with his family. As a country boy living in Las Vegas, he had always felt as if he belonged in a smaller town.

“Vegas has become kind of a small town now in this big area,” he said in an interview Tuesday with the Las Vegas Review-Journal. “This really shows me the love that the people have for the city and that it doesn’t matter who you are and what walk of life you come from. This situation made it so we all have to come together.”

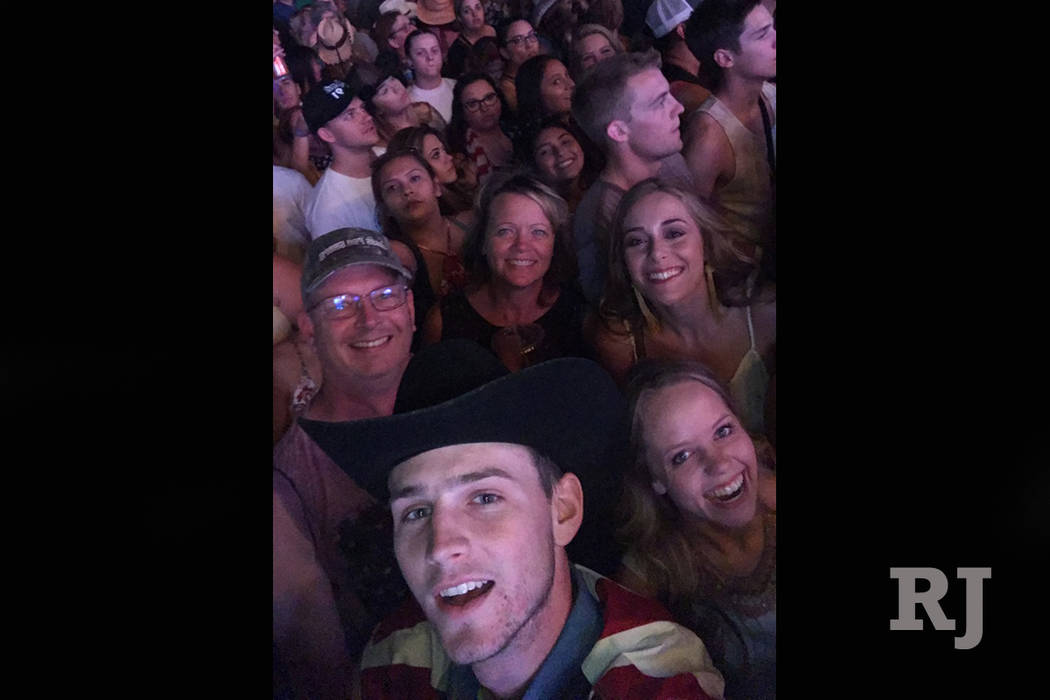

On the night of Oct, 1, he didn’t feel scared. When he realized the continuous snaps were gunshots, the 6-foot-3 young man in the black cowboy hat knew his priorities: get himself and his family out. On the ground, he lay on top of his 22-year-old sister, Taylor, his arm around his mom.

At one point, he and his younger brother, Parker, separated from their parents and sister. As they were some of the last to leave the venue, Schmidt saw throngs of people running back in to help.

Schmidt is suffering from a broken back from a flag football injury. But that night, he ran as fast as he could, he said.

“My back never felt better than when I was getting shot at,” he said.

Schmidt was reunited with his family around 5 a.m. Oct. 2, and he knew he wouldn’t be at school that Monday. When he returned Tuesday, the campus felt somber.

Schmidt resolved to live every day as normally as possible, seeking comfort in his family. He hopes to go to Dallas Baptist University in Texas and become a youth pastor; his mentors at The Crossing Church have helped him cope with events from the festival.

The first Friday after the shooting was Desert Oasis’ homecoming game. There were 58 seconds of silence. It was a challenge to be around large crowds, but he pushed through it. He also pushed himself to watch TV shows with the sounds of gunshots, even though he hears them every day.

But there are still triggers.

Like the day he walked past the forensics science classroom at school. The fake body on the table made him anxious.

Of mice and more

After the mass shooting, teachers were told to stick to routine, Hawks said. The kids would be going through a lot of emotions, and they would need routine and leadership. But they would also need compassion.

The 51-year-old in her 28th year of teaching had never dealt with a tragedy of this magnitude affecting her students before.

During the week right after the shooting, Schmidt walked out of the class on a day when they were studying the Robert Burns’ poem “To a Mouse.” In it, a farmer accidentally runs over a mouse’s nest it had prepared to survive winter. At impact, it literally reads, “Crash!”

“Could this have triggered the more than 300 ‘crashes’ Jake heard that night?” Hawks asked later, after learning he had been at the concert.

She pointed out a theme from the poem, how the best-laid plans of mice and men often go astray. A second theme she discussed is how the mouse is better off than humans because it lives and acts in the now, whereas humans often live in regret of the past or worry about the future.

On the night of Oct. 1, Schmidt and others were acting in the moment.

At the end of that school day, Hawks worried what she could have said in class to make him leave, she said. She picked up the rest of her essays to grade. The next one she grabbed happened to be Schmidt’s.

Reading it, she felt as if she were there. It was real and raw. Her arm prickled with goosebumps.

“He went inside himself to find the good instead of pointing the finger at all the bad he could have noticed,” she said. “For him to see the humanity aspect so early, it really struck me.”

Hawks said she thought more people should see the essay. She shared it with the administration. She shared it with other teachers. “It’s just in him now. There’s no forgetting it or trying to take it out,” Hawks said. “It’s just a part of who he is.”

And what grade did she give him? An A.

Contact Briana Erickson at berickson@reviewjournal.com of 702-387-5244. Follow @brianarerick on Twitter.

An excerpt from an essay written by Jake Schmidt, an Oct. 1 shooting survivor

'"It's easy to look at this moment and say, 'These type of evil actions, such as the one this man carried out, are the reason that I have lost faith in humanity,' But I refuse to believe this," Schmidt wrote in the essay for his English 12 class at Desert Oasis High School. "The day I lose my faith in humanity will be the day that people stop running towards the gunfire, it'll be the day that people are no longer laying on top of one another to save them from the flying bullets, it'll be the day that these strangers watch someone else's daughter, sister, girlfriends, mom or wife die without the intention of helping them."