A Lesson in Humanity

"Consider the fate of this creature's poor mother, struck down in the fourth month of her maternal condition by a wild elephant. Struck down! ... on an uncharted African isle ... The result is plain to see ... Ladies and gentlemen ... The terrible ... Elephant ... Man."

Deformity defines the drama.

Humanity is the point.

"We're telling the story of a man, not the story of a freak," says Terry McGonigle, director of "The Elephant Man," opening tonight at Las Vegas Academy's Lowden Theater for the Performing Arts. "It's a man who never wallowed in self-pity, never looked at the negative, always looked at what good was in his life, the fact that he was alive and breathing."

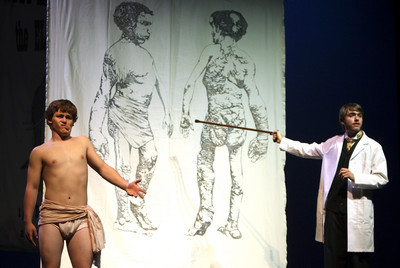

And minus his elephantine features in this production, which forgoes prosthetic makeup, as suggested by the script for the stage play. "The reason is John Merrick was so horribly disfigured that either you can't duplicate the figure he was enough to make it real, or if you came close to being accurate, he's so repulsive to look at that people are distracted and don't pay attention to the actual story," McGonigle says. "In the film, they tried to make John Hurt look like Merrick even though his makeup was not even close to what the real Merrick looked like."

John Merrick: "I am not an elephant! I am not an animal! I am a human being!"

The heart-wrenching, fact-based tale is familiar mostly as the 1980 movie starring Hurt as Merrick, who is viciously abused and degraded as a sideshow attraction in Victorian England.

"This is nothing new to him," says Drew Lynch, LVA's Merrick, about the taunts of the townspeople. "Being looked at is not something he wants, but in his mind, it's, 'If they only knew who I was.' People judge people so quickly."

Mercifully, Merrick is whisked to a London hospital by surgeon Dr. Frederick Treves (Anthony Hopkins in the film, Aaron Fentress in this production). Merrick is initially displayed and scientifically studied, now merely a medical sideshow.

Treves: "Oh, he's an imbecile, probably from birth. Man's a complete idiot ... Pray to God he's an idiot."

But Merrick is soon introduced to members of the cultured class and proves himself a sensitive, intelligent man, along the way teaching Treves, the reserved clinician, lessons in humanity.

"Merrick doesn't pity himself, he takes things lightly, so it strikes a very nice contrast to Treves, for whom everything is very harsh and cut and dried," says Fentress about the detached doctor he portrays, who begins to seriously question whether he is Merrick's righteous rescuer, or merely another callous exploiter. "There is a dynamic change in Treves. He begins to see there is some kind of human in John Merrick, rather than the monster everyone else sees. There is a scene where Treves completely breaks down."

Mrs. Kendal: "Why, Mr. Merrick, you're not an elephant man at all. ... You're a Romeo."

Eventually, Merrick is revealed as a romantic by Mrs. Kendal, a renowned actress who bonds with him and agrees to disrobe to display what he has never seen: a woman's body. It's a scene this high-school interpretation handles modestly.

"We're not playing it how it was played on Broadway," McGonigle says. "We're keeping it very tasteful." Adds Lynch: "It's a step to becoming human as a male. There was a passion inside of Merrick, and when he reaches that, he's gotten to manhood."

Treves: "What is it, John, what's the matter?"

Merrick: "It's just that I --I'm not used to being treated so well by a beautiful woman."

For all the tragedy and tears, there are flickers of humor. "They're talking about God and Merrick has one good hand and he says, 'Who made people?' and Treves says, 'Well, God did,' " McGonigle says. "And Merrick looks down at himself and says, 'Maybe He should have used both hands.' "

Despite the demons that prey upon this angelic soul to the end of his days, the conclusion of "The Elephant Man" leaves the cold reality of his deformities melting in the warmth of humanity.

Merrick: "My life is full because I know I am loved."

Contact Steve Bornfeld at sbornfeld @reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0256.

PREVIEW What: "The Elephant Man" When: 7 p.m. today-Saturday, Oct. 30-31 and Nov. 1 Where: Lowden Theater for the Performing Arts, Ninth Street and Clark Avenue Tickets: $15; no children under 6 allowed (799-7800, ext. 5103)