Ella Fitzgerald’s legacy inspires two Smith Center tributes

Once upon a time — make that twice — two little girls, living worlds apart, heard the same enchanting voice, then began to sing along.

One was in Cairo, the other in Chicago.

And this month, the two grown-up performers will be at The Smith Center’s Cabaret Jazz to sing the songs, and celebrate the singer, who inspired their musical journeys: Ella Fitzgerald.

First up, this Saturday: Las Vegan Michelle Johnson’s “Strictly Taboo,” a salute to Fitzgerald and other jazz divas (including Sarah Vaughan, Billie Holiday, Eartha Kitt, Peggy Lee, Nina Simone, Dinah Washington, Etta James and more) featuring not only their songs but their stories.

Next, on July 22, Ann Hampton Callaway arrives with “The Ella Century,” exploring the life and artistry of “one of the most important singers of the 20th century,” Callaway says in a telephone interview from her New York base.

Unlike Callaway’s solo show, Saturday’s “Strictly Taboo” spotlights a 17-piece big band (led by Joe Escriba), six guest singers and dancers.

“When people think about Billie Holiday or Ella Fitzgerald, they think these singers are interchangeable, which they are not,” Johnson says before a recent rehearsal.

“As a kid, I listened to all those singers and they all evoked something,” she adds.

But Fitzgerald emerged as first among equals when Johnson heard Fitzgerald’s classic “Songbooks” series, in which Fitzgerald delivered definitive versions of standards by George and Ira Gershwin, Irving Berlin, Cole Porter, Jerome Kern, Duke Ellington and more — the songs that make up what’s now known as “The Great American Songbook.”

Those recordings “literally shaped the way people thought about standards,” Callaway explains, likening them to “the Encyclopedia Britannica.”

Johnson calls those recordings “the reference point — the bible.”

They certainly were for her, when she first heard them as a child growing up in Cairo, where her father was the Liberian ambassador to Egypt. (Her mother was a teacher from Detroit.)

There, “getting American records was a big to-do,” Johnson recalls, noting how, at age 6 or 7, she would listen to the same song as performed by different singers — Fitzgerald, Vaughan, Washington — and then “memorize and study the phrasing and inflections.

“To a lot of people, it all sounds the same,” she says, “but it’s not.”

Like Johnson, Callaway first heard Fitzgerald as a little girl, when her father, John — an award-winning broadcast journalist — would bring her records home.

“My dad loved to scat sing,” says Callaway, who followed in his footsteps.“I was scat singing at the age of 3, because of Ella.” (Her mother, Shirley, is a singer, pianist and vocal coach. Callaway’s sister Liz, a Tony nominee, has joined Ann on everything from their show “Sibling Revelry” to the theme song for the TV sitcom “The Nanny,” which Ann wrote.)

Callaway first paid tribute to Fitzgerald on her 2005 album “To Ella With Love,” and with “The Ella Century,” she continues exploring how “a person’s life affect(s) their art,” she notes. “It’s a subject that never stops revealing new treasures.”

Similarly, “Strictly Taboo” goes beyond the songs to provide background details, says Johnson, who previously presented Cabaret Jazz shows focusing on the songs of Carole King and Prince.

“People don’t know about her life,” Johnson says of Fitzgerald, who was a songwriter and bandleader as well as a vocalist. “We did a lot of research into what made (her) tick.”

Ultimately, however, it’s the singer and her songs that resonate with Johnson and Callaway.

“Strictly Taboo,” for example, uses some arrangements sanctioned by Fitzgerald’s estate, “note by note, how Ella would have played it,” Johnson says. When she first went over the charts, “I had goose bumps.”

Listening to Fitzgerald’s happy, playful approach to music taught Callaway “how to harmonize and how to swing,” but also how to “open up and let go and be totally in the moment,” she says. “If you forget a lyric, you’re a scat singer — make up a better one.”

Ella Fitzgerald: the life behind the legend

When the Society of Singers, a charitable group for professional singers, presented its first lifetime achievement award in 1989, they named the accolade after its initial recipient: Ella Fitzgerald.

“The First Lady of Song” was born April 25, 1917, which makes 2017 her centennial year.

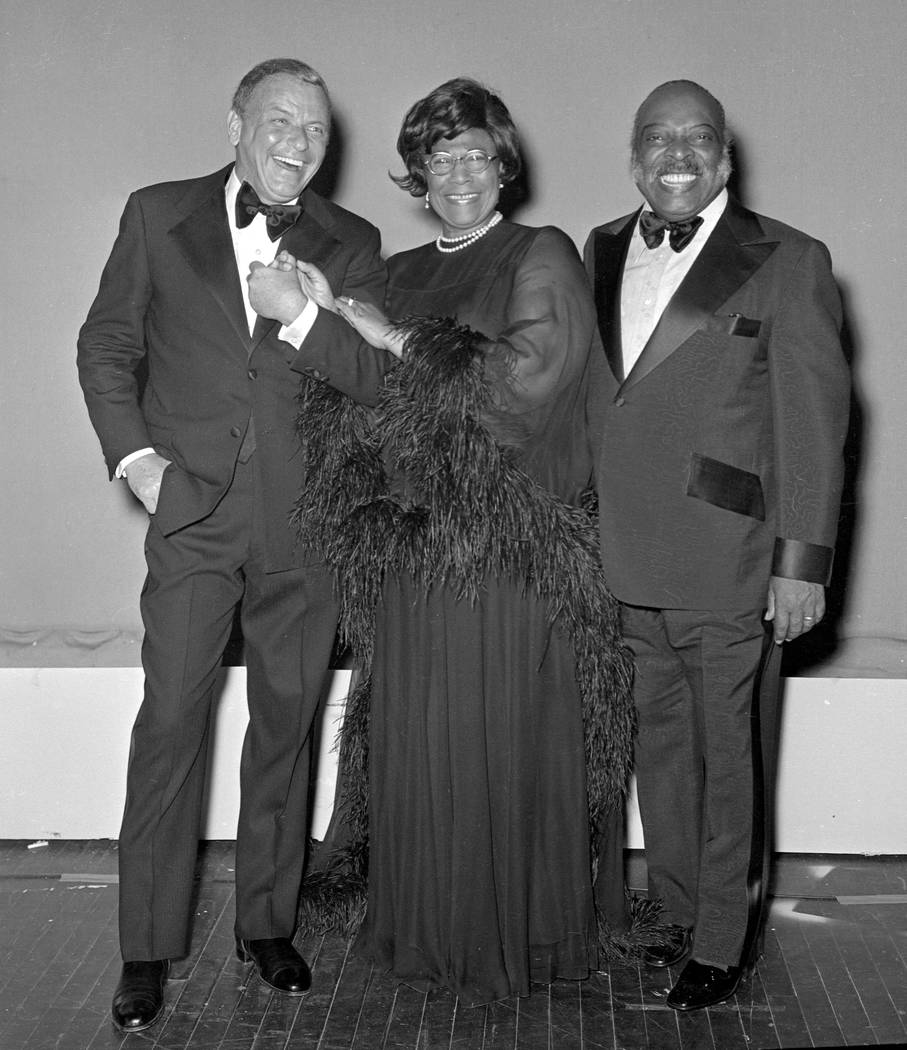

Yet the hoopla surrounding Fitzgerald’s centennial pales in comparison to, say, Frank Sinatra’s, notes singer Ann Hampton Callaway, who brings her “The Ella Century” to The Smith Center’s Cabaret Jazz on July 22.

Sinatra was “a very strong personality — not just a man but also a myth,” she notes. Fitzgerald, by contrast, was “a very humble woman” who “wanted to make people happy.”

Not that Fitzgerald was always happy.

During her troubled childhood, her parents separated and she worked as a messenger running numbers — and as a brothel lookout. Following her mother’s death, she moved in with an aunt, skipped school and eventually wound up on the streets.

At 15, she entered an amateur contest at Harlem’s renowned Apollo Theater, winning the $25 first-place prize — which led to her joining drummer Chick Webb’s band and scoring her first No. 1 hit, 1938’s “A-Tisket, A-Tasket” (which she co-wrote). Following Webb’s death, Fitzgerald took over his band.

In the 1940s, Fitzgerald began working with Norman Granz — the future founder of Verve Records, where in the 1950s she would record “Ella Fitzgerald Sings the Cole Porter Song Book,” the first of her legendary composer tributes.

At the first Grammy Awards in 1958, Fitzgerald won two, for her Duke Ellington and Irving Berlin recordings, becoming the first African-American woman to win a Grammy.

Eventually, she won 13 Grammys — and sold more than 40 million albums — before ill health (including heart surgery and diabetes-related blindness and leg amputations) ended her singing career; her final performance, in 1991, was at New York’s Carnegie Hall. She died five years later.

Callaway never got the chance to work with Fitzgerald, but she did participate in a Carnegie Hall concert celebrating her legacy.

“I do feel music is the bridge between heaven and Earth,” Callaway says, “and at Carnegie Hall, I felt her smiling and dancing.”

Contact Carol Cling at ccling@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0272. Follow @CarolSCling on Twitter.