Neuroscientist-turned-artist presents first show in Las Vegas

Name a female scientist.

Could you do it?

If you struggled to come up with a name — and it was probably Marie Curie — you’re not alone. And that’s exactly what neuroscientist-turned-artist Amanda Phingbodhipakkiya is hoping to change in her first ever large-scale solo exhibition “Connective Tissue.”

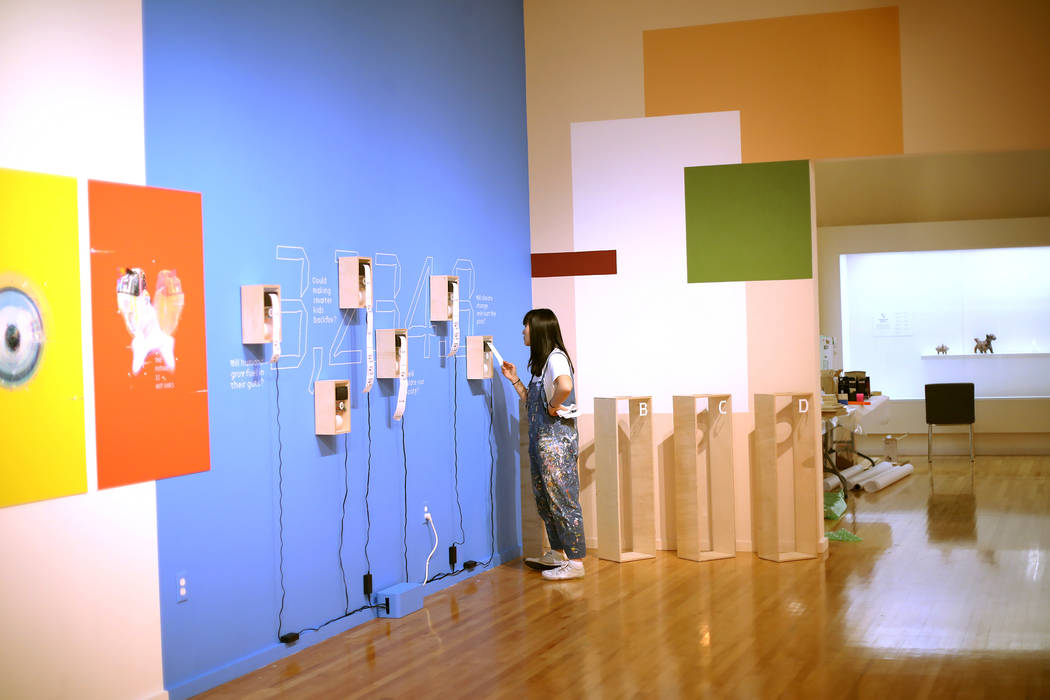

In her exhibition at the Marjorie Barrick Museum of Art at UNLV, Phingbodhipakkiya has designed an investigation of connection — from social relationships to subatomic particles — through the lens of science and technology.

Using bold murals, interactive inflatables and hands-on tech, “Connective Tissue” aims to remind visitors that women not only have a place in science now, but historically, always have.

“If we are to solve the most pressing challenges of our time, it’s ignorant to leave out half the population,” says Phingbodhipakkiya (pronounced PING-bodi-pak-e-yuh). “It doesn’t serve us as a society if we don’t have the perspective of women. And we can’t get it if they never get to consider where they can make a difference.”

Phingbodhipakkiya, 31, first identified the relationship between art and science as a child, when she took notice of butterfly wings.

Her mother got her a microscope so she could better observe them.

“I thought about how science, art and design are all intertwined,” she says. “I’m not sure why they’re so separated in education.”

She went onto study Alzheimer’s disease at Columbia Medical Center, and then study design in graduate school.

From there, she created “Beyond Curie,” a design project that portrays significant women in science, technology, engineering and mathematics, commonly known as STEM subjects.

The posters of women struck a nerve and earned prominent positions in protest marches, magazines and classroom walls.

Members of UNLV’s Scientista club learned of “Beyond Curie” through Phingbodhipakkiya’s TED Talk and invited her to visit them.

During that visit, she met Alisha Kerlin, executive director of the museum.

“That was about two years ago and we started talking about doing an art show,” Kerlin says.

For about a year, Phingbodhipakkiya illustrated vibrant murals of women supporting each other, printed 3D busts of female scientists and experimented with air pressure sensors to design works that illustrate connection.

One work, called “Campfire,” is tucked inside an illuminated person-sized paper lantern. When visitors are seated in all three inflatable lounge chairs, the room glows with joyful hues. But when one person leaves, the lights dim and turn cold.

In a similar work, a familiar piece of music is isolated by each instrument into five sound boxes. Only when each box is activated can someone hear every element of the song.

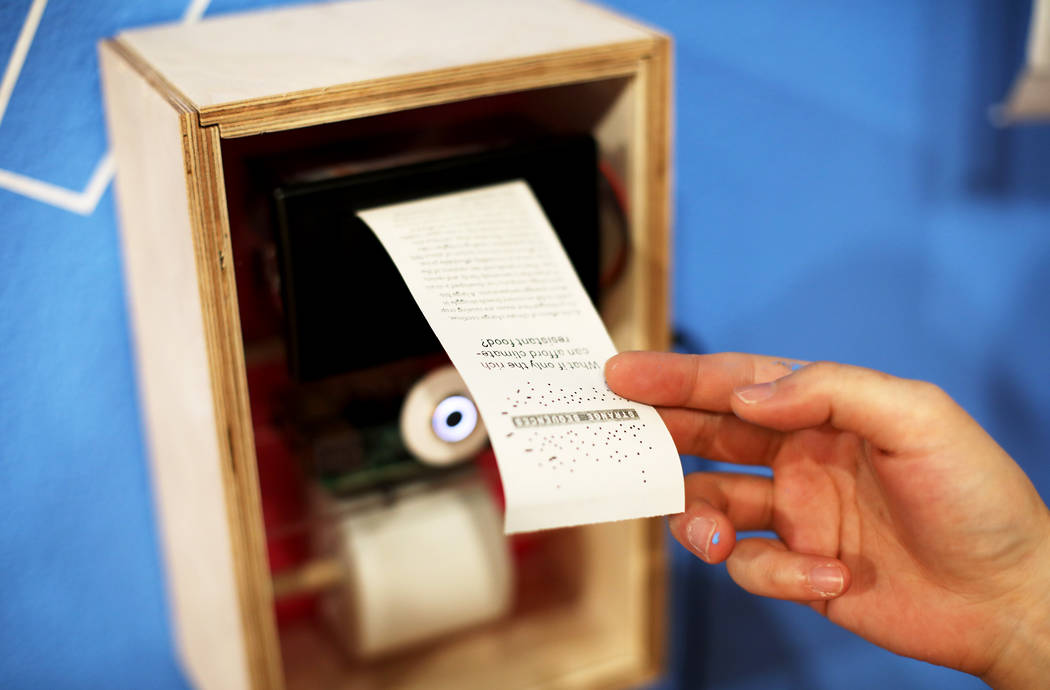

In another, a series of boxes initiates interpersonal discussion by printing slips of paper with bioethical quandaries on them, such as “What if a painful animal vaccine is the only way to contain an epidemic?”

“These questions are based off research currently being done,” Phingbodhipakkiya says. “But we present the scenarios in a more creative, inviting way where, hopefully in the company of loved ones, they feel more comfortable discussing it,” she says.

Visitors can then deposit the slips into voting boxes, which dispose of the paper and create an infographic over time demonstrating the community’s stance.

In the largest sculptural piece the gallery has ever had, Phingbodhipakkiya has designed a massive representation of two electrons passing a photon between them.

“This is taking something so small, even some scientists have trouble seeing and sensing it,” she says. “My work is trying to make people think more critically about our human experience by making something so big, you can’t ignore this thing that is so fundamental to your existence.”

At the gallery’s center, she displays the busts of women in science, equipped with QR codes that allow visitors to learn more about them.

“Only 7 percent of busts are of women,” she says. “The rest are of dudes. And these ones look like marble but were made with one of the latest technology.”

Through February, over 2,000 kids — many of them girls in grades 6 through 8 — will take field trips to “Connective Tissue” through grant-funded programs.

In a city without a major art museum, for many students, this will be their first time stepping foot inside an art exhibit.

“For people who have never walked into a space like this, I want the work to not only say ‘hello’ but ‘please come in,’ ” Phingbodhipakkiya says. “I hope visitors will come away feeling like they have a deeper understanding of the human experience.”

Contact Janna Karel at jkarel@reviewjournal.com. Follow @jannainprogress on Twitter.

If you go

■ What: "Connective Tissue"

■ Where: Marjorie Barrick Museum of Art

■ When: 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. Monday through Friday; noon to 5 p.m. Saturday, through Feb. 22.

Artist talk with Amanda Phingbodhipakkiya: 7:30 p.m. Oct. 10

College of Fine Arts 2019 Art Walk: 5 to 9 p.m. Oct. 11

■ Admission: Free