Discover the trail of black history in Las Vegas

Though Las Vegas isn’t particularly known for keeping history alive, aspects of the African-American community have been preserved throughout the city.

Each of these spots, whether entire neighborhoods or specific houses, tells the story of the black community’s development, says Claytee White, oral histories research director at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

The African-American community’s story starts in 1904, when J.T. McWilliams buys about 88 acres of land.

When the railroad comes in 1905 and started developing on the east of the tracks, the land was mostly vacant.

“Then we fast forward to when the federal government wanted to build a post office and courthouse,” White says.

The site proposed on Stewart Street was where black residents lived in town. White says people were pushed out of the area and began settling in the west side, which was the start of West Las Vegas.

When black residents were barred from businesses in other parts of Las Vegas, West Las Vegas became a haven for them.

In 1942, the Jackson Street Commercial District opened and featured many black-owned establishments, such as a grocery store, barber shop, beauty shop, recreation center, restaurant, drugstore and a gas station. The district also developed many gaming establishments and clubs that were designed for black patronage — though White says not all of these places were owned by black residents.

Places such as Brown Derby Club, the Town Tavern, El Morocco Club and the Harlem Club were bustling at night and on occasion even brought out black performers who performed on the Strip.

The Town Tavern, renamed the New Town Tavern in the ’50s, was the last to survive.

“But that went away about a year ago,” White says.

When segregation ended, many of the businesses dried up because money was no longer kept within the black community.

The Jackson Street Commercial District is listed on the city of Las Vegas’ Pioneer Trail tour.

During the ’40s and ’50s, hotels sprung up around Las Vegas, often installing shows with big-name performers. Prominent black performers such as Sammy Davis Jr. or Lena Horne packed showrooms in these hotels. But policies on segregation prevented these stars from staying in the hotels where they performed.

In 1942, Genevieve Harrison opened a boarding house — now known as Harrison House — at 1001 F. St. to accommodate black performers. They not only stayed at the house, many became part of the community.

White says people who lived in the neighborhood as children remember waiting for Nate King Cole to come out.

“They would have their report cards, and he’d ask to see their grades,” she said. “He’d give a quarter for good grades.”

The house didn’t just cater to black entertainers. People seeking a divorce would stay at Harrison House waiting out the six-week residency requirements.

The house started as a one-room house. As its popularity grew, Harrison added two more bedrooms, a parlor and the dining room.

After segregation ended in Las Vegas, there was no more need for the house. But the property remained.

In 2014, it received a historical designation by Las Vegas and Nevada.

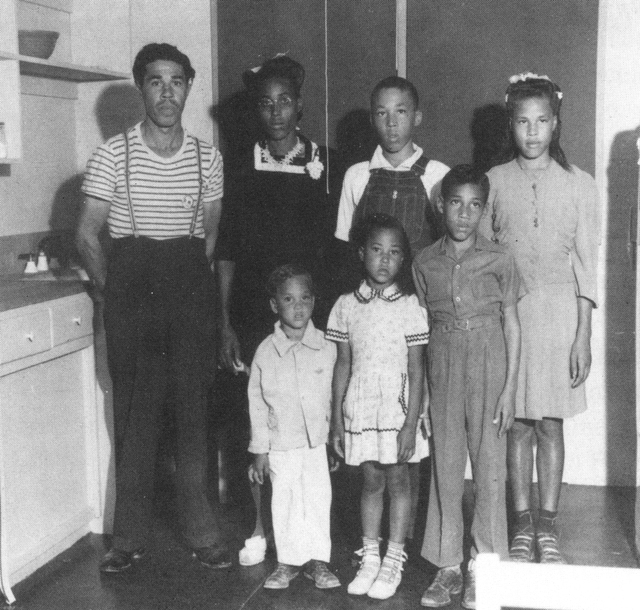

Many of West Las Vegas’ older houses are still around, especially in the area of Berkley Square, near Owens Avenue and D Street.

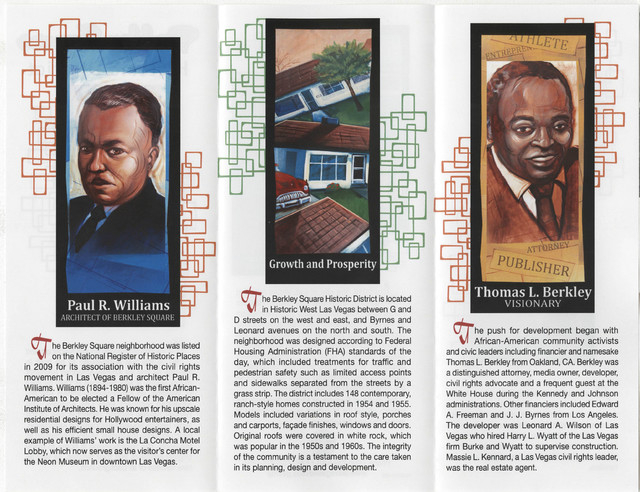

The area, developed in 1954, was originally named Westside Park and was designed by Paul R. Williams, the first African-American architect inducted into the American Institute of Architects.

White says many blacks who moved to Las Vegas, such as Dr. James McMillan, the city’s first black dentist, and Charles West, the city’s first black doctor, bought houses in the area.

Not far from West Las Vegas is the site for what used to be the Moulin Rouge.

Though parts of the buildings burned down in the 2000s and the rest of the complex was demolished in 2010, the site is listed on the Las Vegas and National Register of Historic places for its contributions to the community.

The Moulin Rouge opened in 1955 as the first integrated property. Performers such as Sammy Davis Jr., Dinah Washington and Gregory Hines could be seen at the Moulin Rouge.

The Moulin Rouge was open only for about six months. But in 1960, it served as spot where activists and black community members met with the police chief, mayor, county commissioners and other leaders to discuss segregation at Strip properties. White says the Moulin Rouge Agreement was initiated there and segregation at Strip properties was mostly ended.

African-Americans have had impact beyond West Las Vegas. Williams, the architect who designed Berkley Square, also took his place on the Strip by constructing the front lobby of La Concha Motel. Though the property is no longer around, the lobby was moved to the Neon Museum. The Moulin Rouge’s original sign is also at the museum.

The city of Las Vegas also lists many other landmarks connected to the African-American community.

A Las Vegas Historical walking tour designed by the city that goes through West Las Vegas also includes Christensen House, aka the Castle. It was built by black resident Lucretia Tanner Christensen Stevens in 1935.

The Las Vegas Grammar School, listed as a Las Vegas historic place, was built in 1923 and served mostly black, Hispanic and Paiute children.

Though it isn’t listed as a historical site, the Martin Luther King Jr. statue on the corner of Carey Avenue and Martin Luther King Boulevard is also an important black community fixture. It is often a meeting place for rallies and demonstrations.

Contact reporter Michael Lyle at mlyle@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-5201. Follow @mjlyle on Twitter.