9/11 memories fresh for Las Vegas man who worked at Ground Zero

Duane Matters didn’t want to work at ground zero at first. He didn’t want to face the destruction. The people lost. The wreckage.

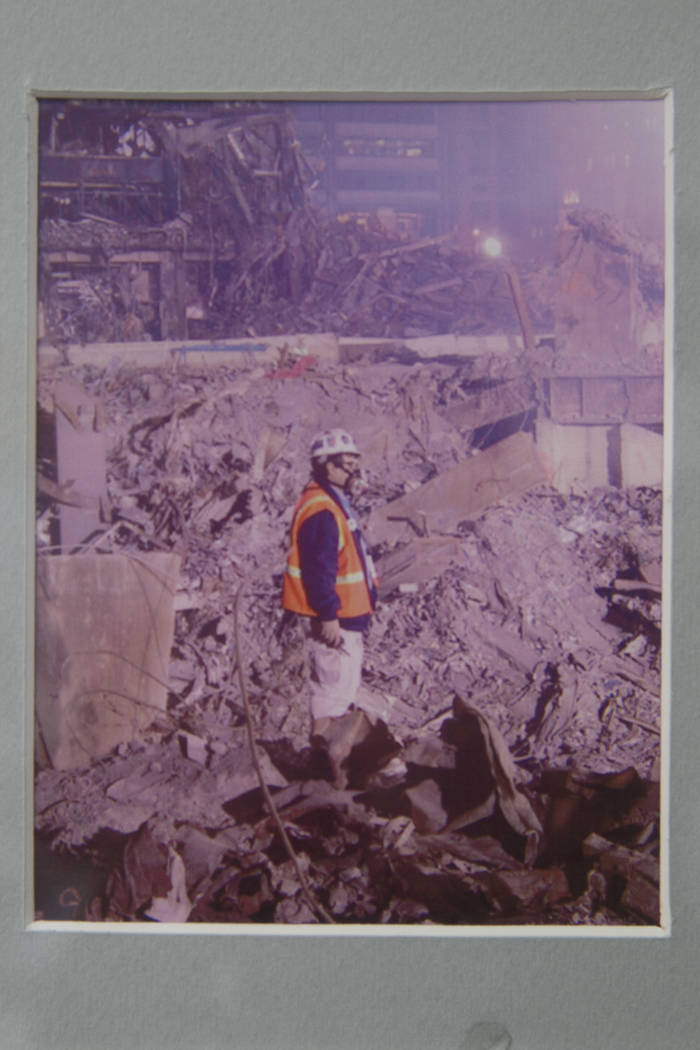

The geologist, now 57, had been to many demolition and earthquake sites. But he knew that the spot where the jet-pummeled World Trade Center had collapsed in New York would be “a most dangerous place,” he said. Nothing like what he’d seen before.

With the 16th anniversary of the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks Monday, Matters’ experiences are still fresh.

“It was a huge, unifying event,” he said of 9/11. But he quickly learned that in trying times, “you can choose to be at your best. If things are so bad, you can step up and be good.”

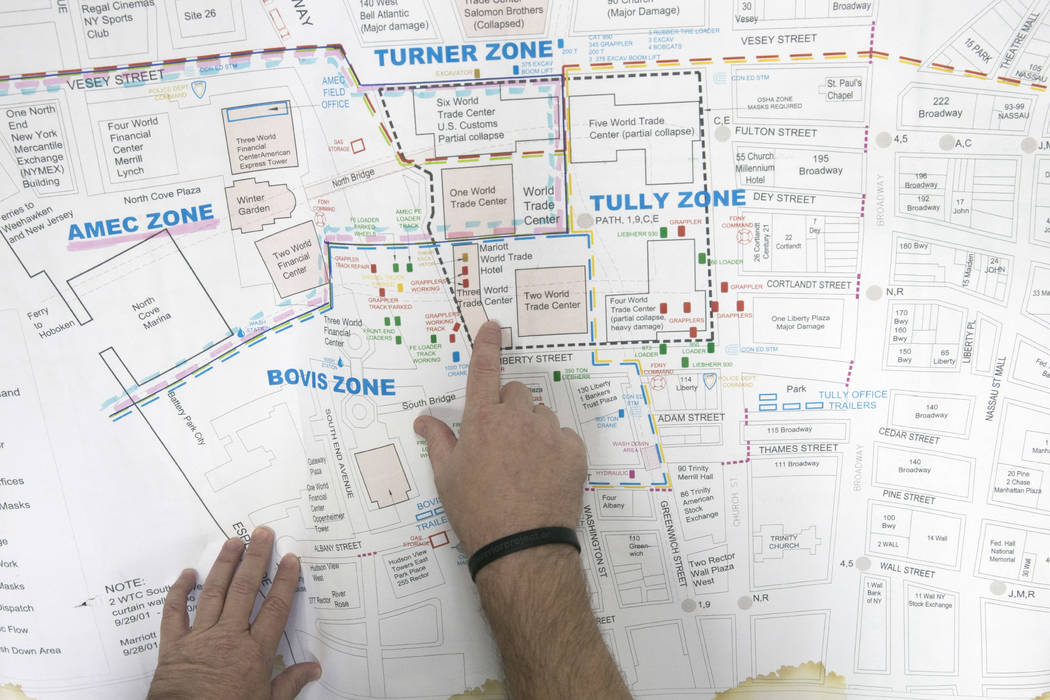

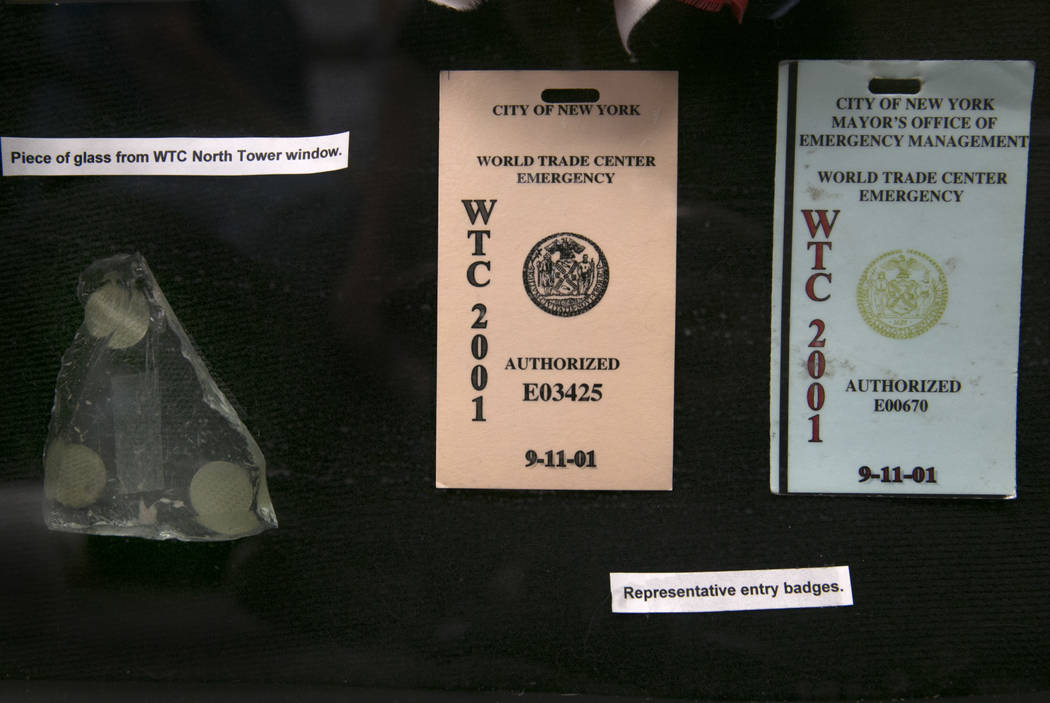

On Sept. 15, 2001, Matters was working for Boston-based engineering consulting company AMEC and was assigned to go to ground zero for a week.

“Keep your chin up,” his father, Duane Matters Sr., told his son before he left.

Before arriving in New York, Matters had 9/11’s victims on his mind. The Hansons, a family from his hometown in Massachusetts, died on their way to Disneyland for a vacation. The youngest was a 2 -year-old girl.

He still visits their memorial when he can.

Before getting to his second checkpoint, Matters extended his stay. He called his family every morning.

“We encouraged him to talk, we did,” said Matters Sr., a 30-year Air Force and Vietnam War veteran. “He was determined to stay and do as much as he could.”

The younger Matters, who now lives in Las Vegas and works at environmental and engineering consulting company Terracon, put in 12- to 18-hour night shifts at ground zero. He took only three days off in seven months.

Matters Sr. remembers two things staying with his son from his time in New York: the people who gave him pictures of missing loved ones and asked him to watch out for them, and the rescue dogs he met. He kept track of what happened to them after they left.

“It gave him a mission. He has stuck with that ever since,” the elder Matters said.

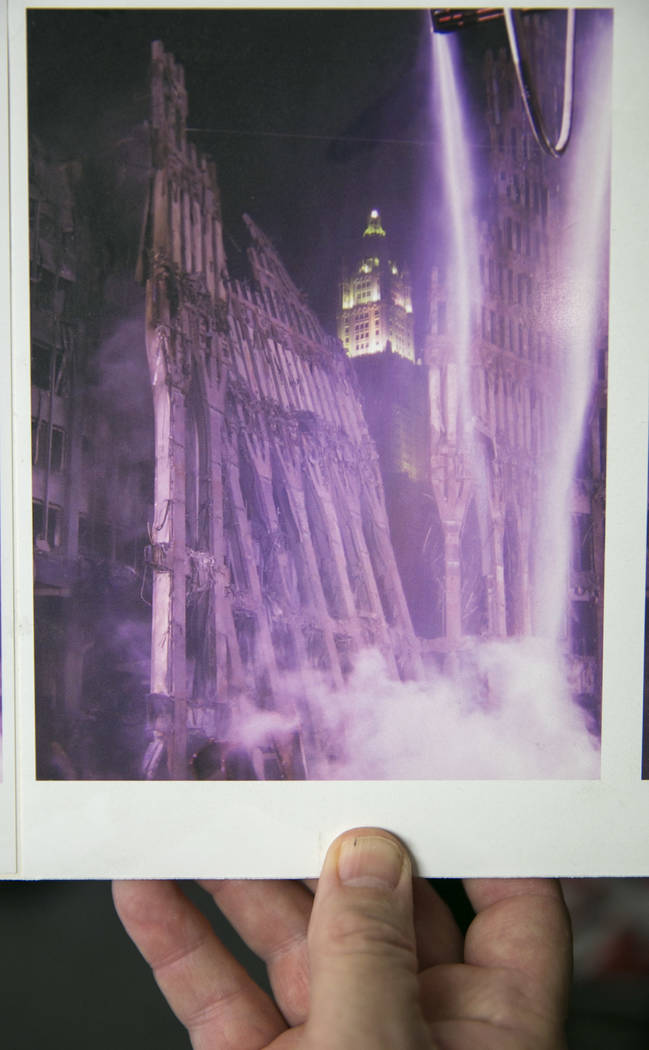

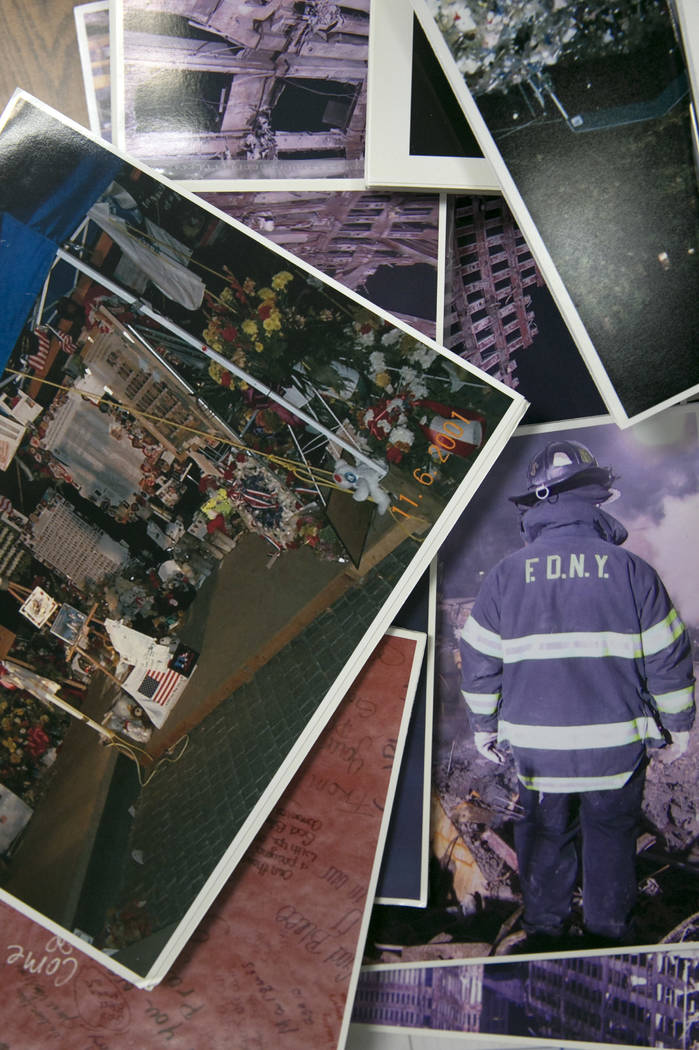

The ground zero work was harrowing. Fires at the site burned deep down in the rubble pile and burned for months, into early January. When a person’s remains were found, they were draped in an American flag.

The fires were so bad that Matters went through three pairs of boots in the first month. He called the Red Wing boot store on West Charleston Boulevard for a new pair and one was sent, gratis.

“He held up well,” said Matters Sr., 83. “I hope we had something to do with that by talking to him every day.”

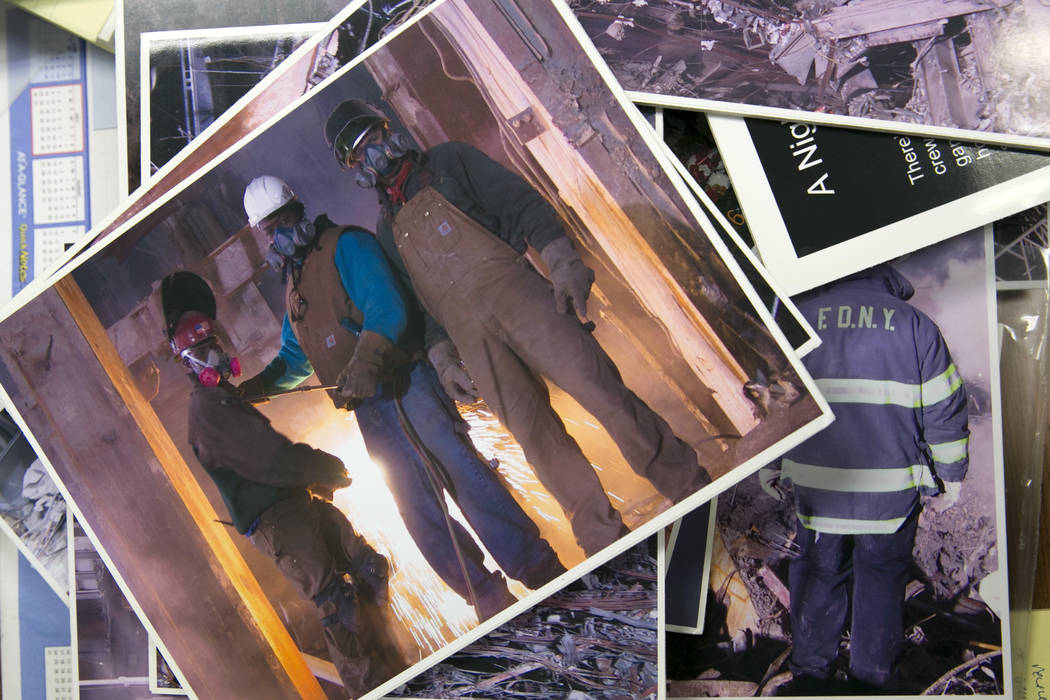

One night, Matters, who wore a bicycle strobe on his hard hat, was out with an operating group, wielding a grappler. He picked up a piece of steel on the pile and exposed an area that was still hot. The spot flared up and burned for about an hour, creating a smoke cone around him, Matters said.

It took large water cannons to douse the area.

“OK,” Matters told himself. “I have to stay put.”

He stayed close to the ground and waited.

He saw smoke dissipating periodically. He came out smoky, wide-eyed and gray-skinned.

Matters said an “alphabet soup of chemicals and compounds” presented a danger at the 12-acre site. He was monitoring for asbestos, oil, gas, silica, charcoal and Freon. With careful footing and quick adaptation, he worked with engineers, scientists, steelworkers, laborers and truck drivers.

“They were all suffering a total loss,” he said. “But they did some amazing things.”

During breaks, the workers slept in the pews at St. Paul’s Church in New York. One of the first places Matters stayed was the Delmonico Steak House, where he was fed and taken in. There, he met a man who had been stationed at Dyess Air Force Base, Texas, at the same time as Matters’ father and his family. He had piloted the last B-52 shot down in the Vietnam War during the Linebacker bombing campaign, Matters said.

If the man didn’t see him when he came back for lunch, he would call him to make sure he was OK, Matters said.

One night, tired after a 12-hour work shift, Matters was getting a pizza with a co-worker. A woman walked up and asked them if they were ground zero workers. She handed them a card with the picture of a young man. On the back of the card was his name, Carl Bini of Rescue 5. She told them he had been missing, then she hugged Matters and the other workers, thanking them for helping bring him home from his last mission.

“When things are at their worst, people are at their best,” he said. “I kind of wish that feeling lasted.”

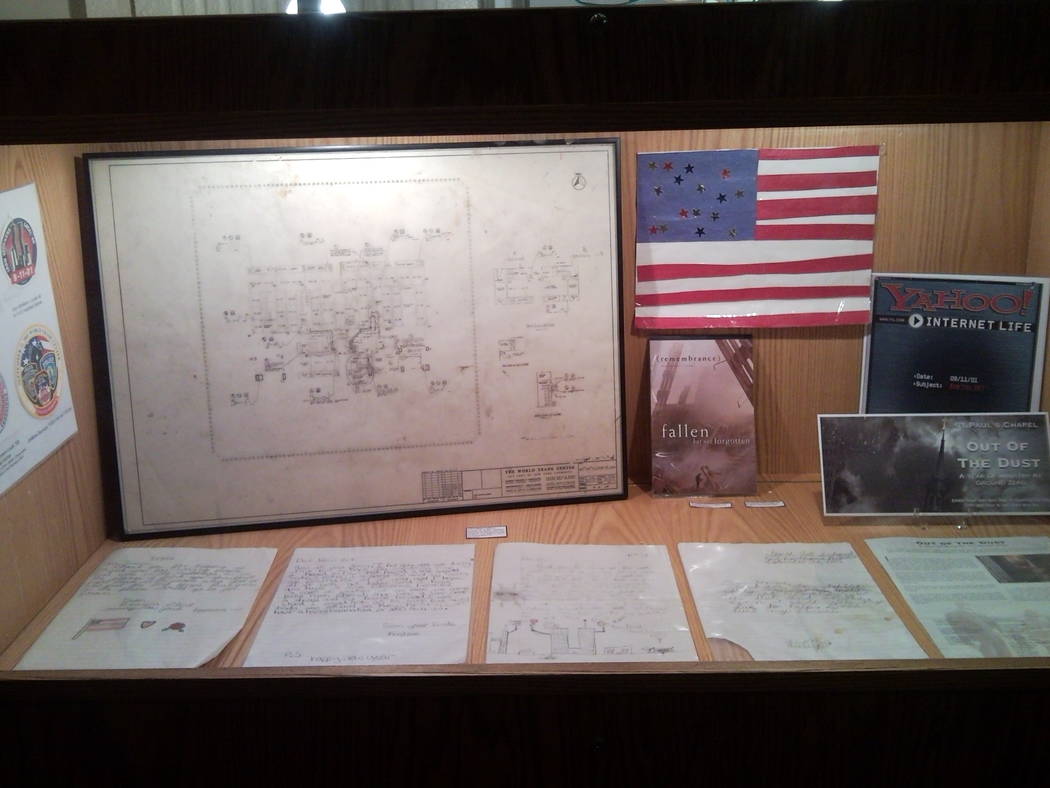

Notes from schoolchildren have particularly touched Matters. He carried one with him for comfort while working at ground zero.

“I am proud of you for being there. … It didn’t just break the hearts of New Yorkers it broke the hearts of the world!” The letter read. “Please keep hard at work.”

After leaving New York in March 2002, Matters found it difficult to return to a regular job.

He was spent emotionally. The 12- to-18-hour work shifts and overnights took a toll on him. So had the destruction — seeing the unrecognizable remnants of people and buildings.

He couldn’t bear going home to work in an office, he said. A 10-foot-by-10-foot space hemmed in by four walls felt like suffocating confinement.

His priorities had shifted dramatically.

“It was a loss of reality,” Matters said.

So he went to Germany for work-related reasons, coping with lung capacity problems related to ground zero’s dust and debris.

Then, in December 2002, he moved to the desert, to be closer to the rocks and canyons.

“The experience put a period and an exclamation point on life.”

Contact Briana Erickson at berickson@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-5244. Follow @brianarerick on Twitter.