As jail alternative, court program helps women turn lives around

On their lowest days on the Las Vegas streets, in and out of jail, neither Bridget Stevens nor Morgan Savage could’ve imagined their lives would get to this moment.

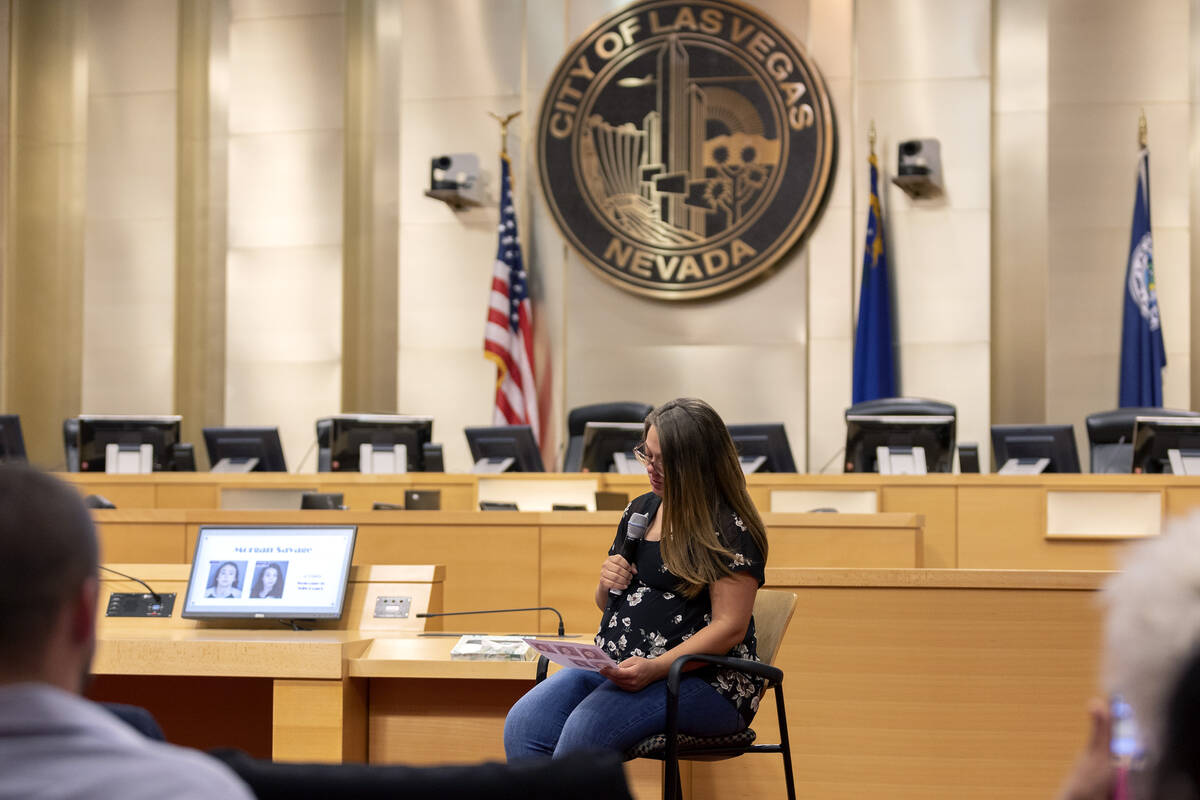

Standing in Las Vegas City Hall’s council chambers, in front of family, friends and supporters, both cried as a judge praised them.

Stevens, 28, and Savage, 23, were graduating from Las Vegas Municipal Court’s Women in Need of Change court program, or the WIN Court.

The program is an 18- to 24-month intensive jail alternative for women whose battles with demons, including drug addiction, homelessness, prostitution, human trafficking — or all of the above — have made them repeat customers in the criminal justice system.

Municipal Judge Cynthia Leung, who oversees the program, said all of the women have one thing in common: trauma. Whether it be physical or sexual abuse, or both, or seeing friends die on the streets, or having grown up in violent households, they are all scarred by trauma, Leung said.

Their often harrowing experiences have caused the women to develop harmful ways of coping, Leung said. The aim is to change how they think about life and how they see themselves.

“You have to get them to buy into their self-worth,” Leung said. “A lot of other things begin to fall into place when they begin to value themselves again.”

Leung, who describes WIN Court as a “gender-specific, trauma-informed speciality court program,” took over the then-year-old program in 2008, bringing it to life and helping almost 60 women graduate since then. Savage was the 57th graduate and Stevens was the 58th.

Both women started the program in January 2021. To graduate, which also meant they would have their criminal cases dismissed and sealed, they had to work the program and turn their lives around.

The program requires participants to get sober, go to therapy, get jobs, repair strained relationships with family and friends if it makes sense to do so, get their GED if they haven’t graduated high school and otherwise break the cycle of addiction and crime.

A number of community organizations work with the program, including behavioral health services providers, sober living facilities and other agencies that offer various means of assistance in the women’s journeys.

On a Thursday in August, Savage and Stevens were celebrated during a ceremony in which Leung told of their stories, beginning with their entrances into the program as broken and addicted young women.

Turning their lives around

Leung showed several mug shots for Stevens and Savage, both of whom had been arrested several times.

“When I look at these pictures, looking in the eyes of myself, I was just so lost and I was so scared,” Savage said.

Now, a year and a half later, Stevens, who has an 8-year-old daughter, Aaliyah, and Savage are both pregnant, sober and look nothing like the defeated women in the jail booking photos.

“It feels a little surreal,” Stevens said. “It feels good. I don’t know — I feel like this is just the beginning of my life. I’m excited though.”

After the graduation ceremony for both women in the council chambers, Savage, Stevens and friends and family walked across the street to the municipal courthouse, where Judge Leung dismissed both cases — each was accused of possessing drug paraphernalia — and ordered them sealed.

Savage, who was only facing 30 days of jail time when she opted to do the program, recounted how it would be harder than jail for her because she would actually have to do the work and not just pass the time.

“All you ladies know that 30 days is nothing,” Leung said, referring to how the women and the others in WIN Court would be in and out of jail so much that a month behind bars for them was no big deal.

“You took a 24-month program instead of 30 days!” Leung remarked.

In an interview afterward, Leung said that while she hopes to see trauma-based specialty court programs like WIN help more women in more jurisdictions, the program is not for everyone.

For instance, while many offenders have experienced trauma in their lives, some aren’t suitable for specialty court programs because they might not be ready to be held accountable. Or they might put other participants at risk if they’re sociopaths or predators, she said.

Plus, most of the women in WIN Court get tangled up in the justice system because of misdemeanor offenses, low-level crimes that reveal much-deeper issues going on in their lives such as homelessness or addiction. They are not hardcore violent offenders.

“Not everybody is a good candidate for a specialty program,” Leung said. “There are folks who need jail and jail is an appropriate accountability for them.”

‘Taught me how to live my life’

Outside the courtroom, after their cases were dismissed, Savage and Stevens spoke of how different they are now from the women they were.

“I was addicted to heroin, meth, anything I could get my hands on. I was homeless. On the streets,” Savage said. “Well, now I have a healthy relationship with my boyfriend and we live in a house that he owns. I’m about to have a baby. I have money saved and I have my family in my life.”

Stevens, too, has experienced similar change and growth.

“I was lost for sure. Wild. I just ran the streets. I was a menace to society, to say the least,” she said. “I’ve grown up a lot.

“I feel good. I feel great. I know it’s not over,” Stevens said. “What I went through helped me grew up, but then this court program helped mold me and taught me how to live my life and how to live responsibly and being accountable for myself. So now it just feels great.”

Contact Brett Clarkson at bclarkson@reviewjournal.com or 561-324-6421. Follow @BrettClarkson_ on Twitter.