Fatal Las Vegas crash in 1958 led to modern air safety system

It is the worst air disaster in Las Vegas history, and there’s no telling how many lives it saved.

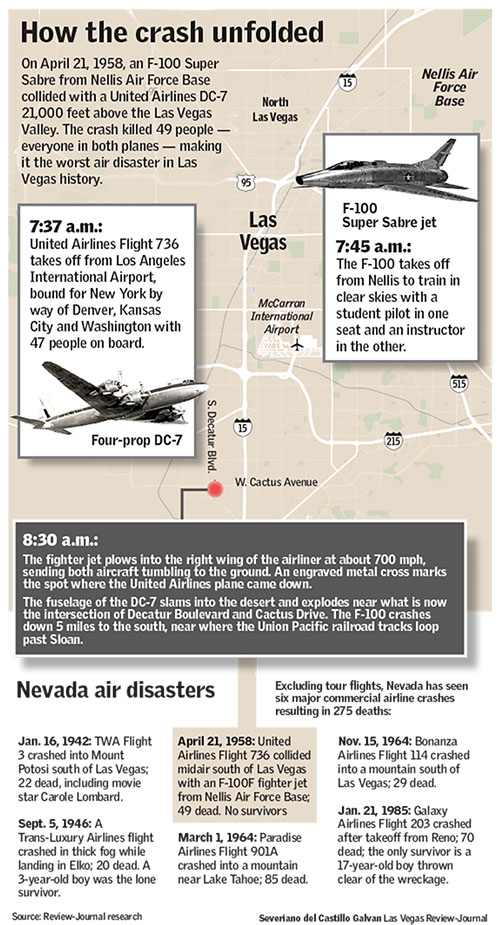

On April 21, 1958, 60 years ago Saturday, a fighter jet from Nellis Air Force Base and a United Airlines flight from Los Angeles collided 21,000 feet above the southwest valley.

The two men in the jet and all 47 people on board the airliner were killed when their crippled planes tumbled to the ground and exploded.

The crash led directly to changes in the way airspace nationwide was shared by commercial and military flights, and it ushered in widespread improvements in air traffic control.

In August 1958, President Dwight Eisenhower specifically referenced the deadly collision over Las Vegas as he signed the Federal Aviation Act, which ordered the creation of what is now the Federal Aviation Administration.

“It was a game changer,” said local aviation historian Doug Scroggins, who has researched the crash extensively. “This accident definitely saved lives with the changes that were made after it. There’s no doubt about it.”

‘Nothing they could do’

United Flight 736 was destined for New York with scheduled stops in Denver, Kansas City and Washington. The four-prop DC-7 was half full when it left Los Angeles International Airport at 7:37 a.m.

Eight minutes later, an F-100 Super Sabre took off from Nellis with a student pilot in one seat and an instructor in the other.

At 8:30 a.m., the planes’ paths intersected about 9 miles southwest of where McCarran International Airport is now.

Clark County Museum administrator Mark Hall-Patton said the Air Force jet was practicing a maneuver that involved climbing to about 28,000 feet and diving almost straight down to simulate a rapid insertion into enemy airspace.

The sky was clear and visibility excellent that morning, Hall-Patton said, but the student pilot was wearing a hood to practice flying using only the instruments in the cockpit.

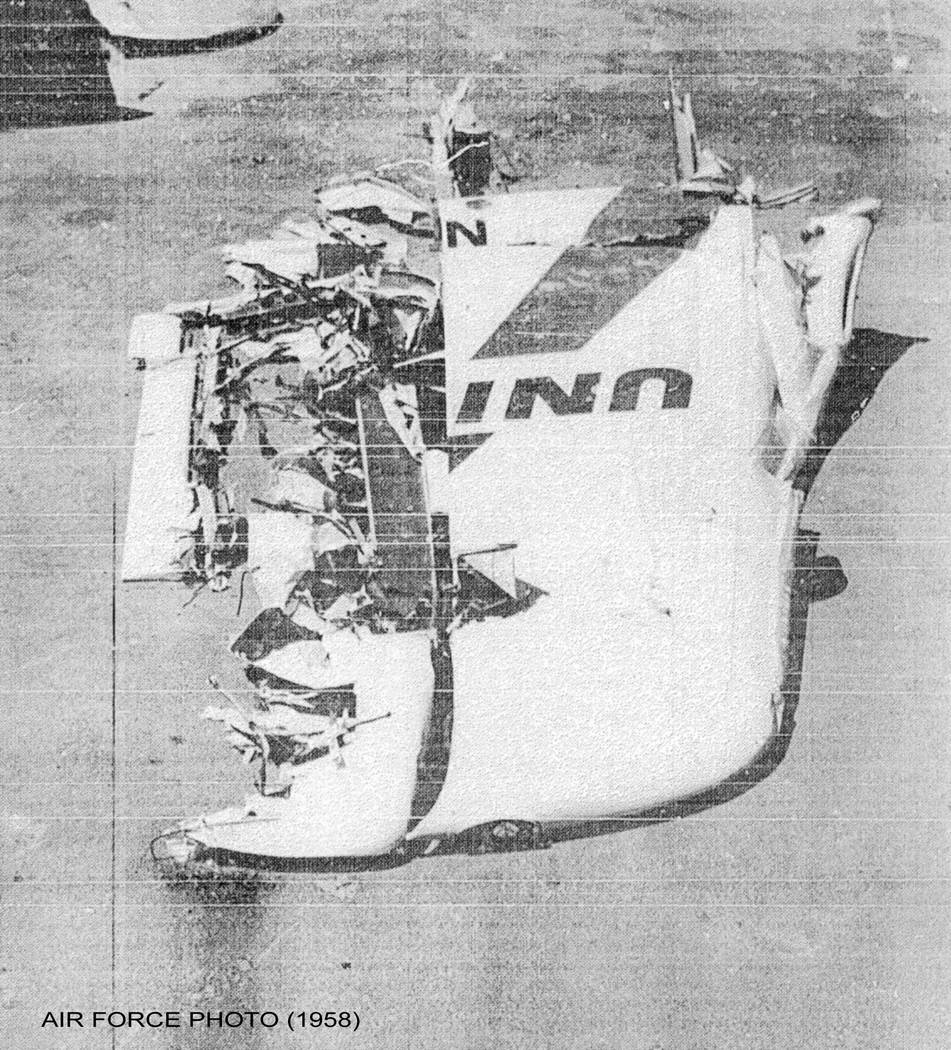

He said the F-100 was traveling at more than 700 mph when it struck the right wing of the prop-driven airliner, sheering off a 12-foot section near the tip.

Several Las Vegas residents who saw the impact reported a puff of smoke, a flash of fire and a shower of metal pieces.

In a Las Vegas Review-Journal report the day after the crash, one witness described the airliner as “a spinning ball of fire which exploded intermittently as it snaked toward the earth.”

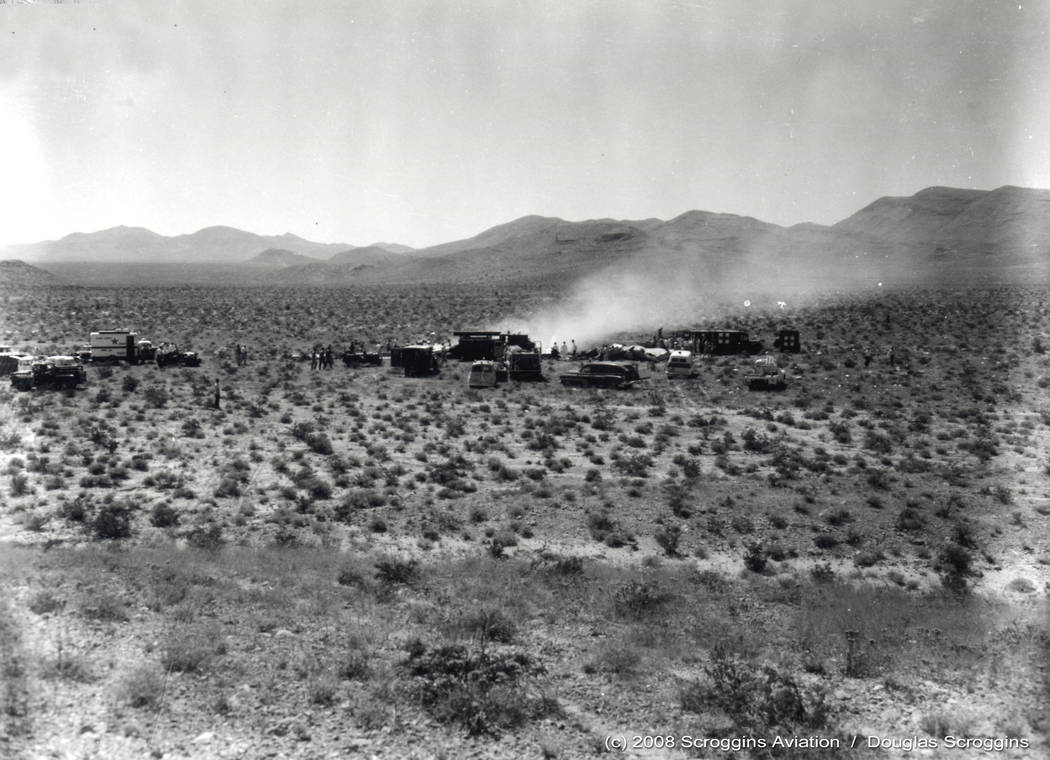

The fuselage of the DC-7 slammed into the ground half a mile from its engines, which were sheered off by the force of the descent. The F-100 crashed and exploded five miles to the south, where the Union Pacific railroad tracks loop past Sloan.

“They both went straight in. There was nothing they could do about it,” said Hall-Patton, whose responsibilities include the Howard W. Cannon Aviation Museum at McCarran.

Site swallowed by suburbia

An engraved metal cross — put up in 1999 by the son of a crash victim — still marks the spot where the United plane came down.

In 1997, Scroggins used old photos and accident reports to pinpoint the mostly forgotten impact site, where he found fragments of dishware stamped “UAL” and several pairs of novelty pilot wings that flight crews would hand out to children.

He later led some family members to the spot where their loved ones were killed.

In 1958, the crash site was an empty patch of desert several miles from the nearest paved road. Now it is the parking lot for a taco joint, a tire shop and a neighborhood bar on Cactus Avenue, just east of Decatur Boulevard.

The cross sticks up from a pile of rocks on a trash-strewn hill behind the parking lot. Scroggins thinks the place deserves something more official and permanent.

“There was a point where we could have bought the property and built a park on it or something,” he said, but development in the area has driven up the price of the land.

“It’d be nice to get something out there, even if it’s just a bronze plaque in the ground,” said Scroggins, who also runs a salvage and effects business that supplies cockpits, passenger cabins and whole planes for movie and television productions.

A legacy of safety

Hall-Patton said the crash also prompted a more obscure regulatory change.

Among the commercial passengers that day were about a dozen people involved in the secret development of the country’s intercontinental ballistic missile arsenal. Their deaths set the Cold War program back significantly.

After that, Hall-Patton said, the military, the defense industry and some large corporations adopted rules to prevent “a critical mass” of technical people from key projects from traveling together on the same aircraft.

But the lasting legacy of Las Vegas’ deadliest aviation accident is one of safety, Hall-Patton said. Airspace is tightly regulated. Air traffic controllers are in constant contact with one another. And supersonic military aircraft no longer practice over cities or through commercial corridors.

“At least something good came from it. It’s why flying is so amazingly safe today,” Hall-Patton said. “If you look at the numbers, it’s an amazingly safe way to travel, and that’s because we continuously learn whenever there is an accident.”

Contact Henry Brean at hbrean@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0350. Follow @RefriedBrean on Twitter.

Nevada air disasters

Excluding tour flights, Nevada has seen six major commercial airline crashes resulting in 275 deaths:

Jan. 16, 1942: TWA Flight 3 crashed into Mount Potosi south of Las Vegas; 22 dead, including movie star Carole Lombard.

Sept. 5, 1946: Trans-Luxury Airlines flight crashed in thick fog while landing in Elko; 20 dead. A 3-year-old boy was the lone survivor.

April 21, 1958: United Airlines Flight 736 collided midair south of Las Vegas with an F-100F fighter jet from Nellis Air Force Base; 49 dead. No survivors

March 1, 1964: Paradise Airlines Flight 901A crashed into a mountain near Lake Tahoe; 85 dead.

Nov. 15, 1964: Bonanza Airlines Flight 114 crashed into a mountain south of Las Vegas; 29 dead.

Jan. 21, 1985: Galaxy Airlines Flight 203 crashed after takeoff from Reno; 70 dead; the only survivor a 17-year-old boy thrown clear of the wreckage.