Friend: Nothing has changed at VA center since Niccum’s death

Dee Redwine’s heart sank when she found out two weeks after Sandi Niccum’s funeral that the video of Niccum’s painful, five-hour ordeal waiting for treatment at the North Las Vegas VA Medical Center’s emergency room had been erased.

“I was just devastated when we received that answer that there was no video. I couldn’t believe it. I still can’t,” she said in an interview to mark the one-year anniversary of Niccum’s ordeal Oct. 22, 2013. The experience was too much to bear for Niccum, a blind Navy veteran and brittle diabetic suffering from a ruptured colon abscess.

Redwine can’t erase that day from her mind.

In a year’s span, she feels nothing has changed that would prevent a similar experience forced upon other veterans. That is because the VA’s use of video surveillance has incorrect priorities, she said. Rather than find a way to retain video evidence of emergency health care problems, local VA managers are more focused on spying on their own staff with a hidden camera.

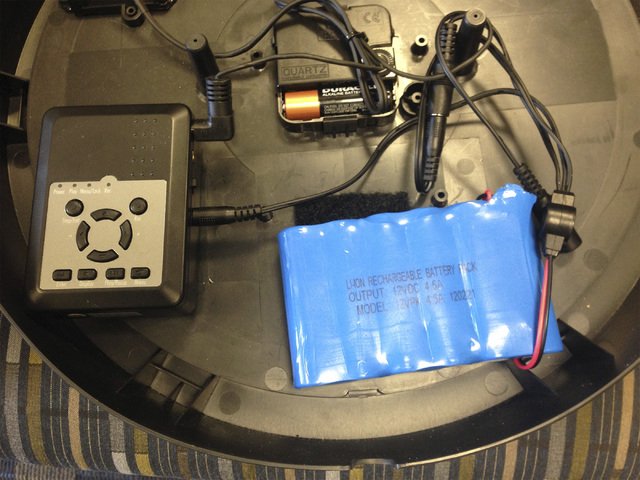

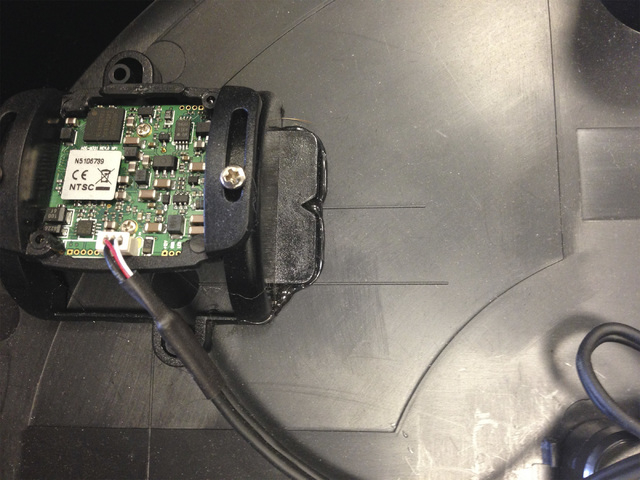

New photos confirm that the VA used a camera concealed in a wall clock as recently as August to monitor staff confrontations, the Las Vegas Review-Journal has learned.

Furthermore, Redwine said, the investigation into Niccum’s ordeal that followed failed because she was the primary witness but was never interviewed in person by the inspectors. The team also sidestepped a key issue: why those who were supposed to be monitoring the video didn’t respond to avert a crisis.

LOOKING BACK

“It began with a phone call from her personal doctor from the women’s clinic saying, ‘Get Sandi to radiology,’ ” Redwine recalled.

“To get Sandi anywhere in her weakened state means to get her up, get her dressed, get her in a wheelchair and get her to the facility,” she said about her 78-year-old friend. “We were told by the physician what they were going to do. … She was on call, and if there was any problems, she would be there.

“None of that happened,” Redwine said. “Everyone is forgetting she was blind.”

Months after the ordeal, health care scandals surfaced at VA facilities across the nation, including in Phoenix where whistleblowers exposed falsified waiting lists involving two sets of records. One set kept track of actual times. The other set altered the real wait times to send to VA headquarters to justify performance bonuses for VA employees.

An audit in June uncovered evidence that a clerk at the Southern Nevada facility might have been directed by a supervisor to alter patient scheduling to mask long wait times, a practice that auditors found widespread in the VA system. VA officials have blamed the long wait times and scheduling debacle on shortages of doctors and health care professionals.

Nonetheless, the revelations spurred the resignation of then-VA Secretary Eric Shinseki in May.

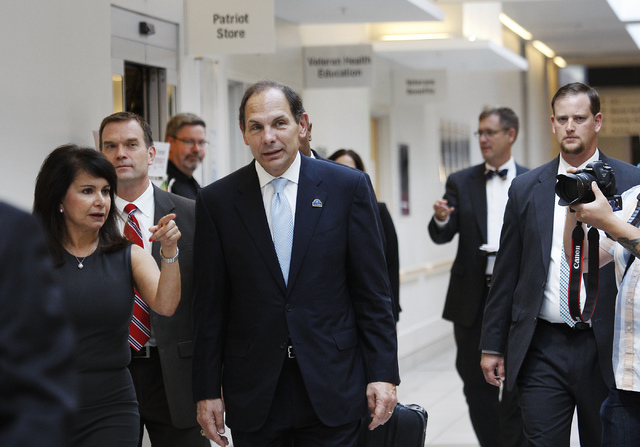

His successor, Bob McDonald, traveled to Las Vegas in August. In his first speech to the National Disabled American Veterans convention, he laid out a reform plan based on transparency to restore trust in the agency.

Yet hours later, as McDonald walked the halls of the North Las Vegas VA Medical Center on Aug. 9, there was a not-so-transparent video camera hidden in a wall clock spying on the workplace.

The Review-Journal obtained photographs of the covert clock camera and asked a VA spokesman to explain why it was there.

“A monitoring camera was (temporarily) placed in a public corridor adjacent to the Voluntary Services main entrance and lobby,” the spokesman, Rich Beam, wrote in an email Thursday.

Beam said the hidden camera was installed “as a precautionary measure” to assess several incidents.

“The allegations included assaults as well as verbal confrontations,” he wrote, adding that the camera was in service and monitored by VA police Aug. 4-19 “but did not substantiate any measure of the allegations.”

PRESERVING EVIDENCE

In an interview less than a month before the hidden camera was installed, VA Southern Nevada Healthcare System Director Isabel Duff discussed the Emergency Department’s video surveillance issue in light of Niccum’s ordeal. When asked about the footage being erased, she stressed that “there was no active deletion. This is how the system is built.”

“We’re a health care organization. We’re not here to be monitoring or ‘surveilling’ people in that way,” she said.

Redwine is bewildered that such effort was made by VA managers to capture video evidence of staff confrontations, yet the hospital’s more extensive video surveillance system wasn’t programmed to retain the footage that would have shown Niccum writhing in pain while she waited to be seen Oct. 22, 2013.

“What has happened for the dignity of our veterans for protecting their safety with surveillance? The priority is backwards. What a shame,” she said.

Redwine was Niccum’s neighbor and shared her enthusiasm for the countless hours they worked as volunteers to serve veterans.

When they reached the hospital’s Emergency Department that fateful day, the triage nurse checked Niccum’s blood sugar level and found it to be so low that she was on the verge of having a reaction.

“After the reaction got worse, I moved her over to the space where there were two double chairs,” she said. She was worried Niccum would pass out.

“I needed to get some food or something in her system to bring her sugar up. Not one person came out and checked on us,” she said.

“Even if Sandi beat on the floor (with her cane) and begged for help. If the surveillance (video) was there, it would show I moved her from the center of that very small room over to the corner” because Niccum’s outbursts would disturb other patients.

“There were only two other ladies in the waiting room,” she said. “She was crying and begging for help.”

PROBING THE PROBLEM

The $1 billion hospital, which opened in 2012, is equipped with an elaborate video system. The control room, monitored by VA security personnel, resembles one from the starship Enterprise in the “Star Trek” TV series, some VA workers have said.

The recorded data are overwritten, or erased, in 30 days, as is done in other VA facilities, according to VA officials. They say the system, which can be set to retain recordings for 90 days, is a tool to monitor the safety of patients.

Regardless, Redwine said that had anyone been watching the video monitor that day, “even (a) nonmedical person would have responded.”

“And there was a lady in real time sitting at the desk who I approached more than once asking for help, asking is there a bed somewhere I can put on the floor, surveillance would have shown all that,” she said.

Counting more than an hour wait before her initial check by a triage nurse, Niccum spent 5 hours, 6 minutes in the VA hospital’s Emergency Department. When she finally was seen by a doctor, she was given a prescription for pain medication. Then Redwine took her home. Niccum returned two days later for tests that showed symptoms of cancer, colitis and a perforated appendix. She died Nov. 15 at a hospice.

In her last days, Niccum asked Redwine to write up a chronology of what happened and submit it to the Review-Journal. A story based on the chronology prompted House Veterans Affairs Committee Chairman Rep. Jeff Miller, R-Fla., and committee member Rep. Dina Titus, D-Nev., to call for an investigation.

In a Nov. 26 statement, Miller said, “We will be asking VA to provide copies of all applicable surveillance camera footage so we can examine the sequence of events in detail.”

The request was received by the VA Office of Inspector General on Dec. 11, according to the IG’s “health care inspection” report. Miller announced the probe Dec. 12, the day of Niccum’s funeral service.

Then in a Dec. 20 interview, Duff revealed that the video recording had been erased automatically and that the contractor who installed the surveillance system had tried to recover the recording but couldn’t.

The 19-page inspector general’s report signed by Dr. John D. Daigh concluded that “a wait of this length was, at a minimum, challenging for this patient. However, mitigating this long wait was the fact that numerous other patients who were assessed to be in more urgent need of attention were in the (emergency department) at the same time.”

The inspection team, however, found “no relationship between the length of the patient’s wait and her subsequent clinical course,” or death.

Redwine believes the report sugarcoats what really happened and downplays the importance of retaining surveillance video because there were no recommendations on archiving footage.

She also is perturbed that the inspection team traveled to the North Las Vegas VA Medical Center to gather information Dec. 17-18 but didn’t interview her in person though she was a key witness and the only person who was with Niccum during the ordeal. Instead, the team interviewed her later in a conference call.

“I expected when they were here in Vegas that I would see them personally, that they would want to see who I am, maybe check out my character,” Redwine said. “I was just surprised everything was just nonchalant and on the phone. That’s pretty disappointing.”

Asked why Redwine wasn’t interviewed in person, a spokeswoman for the VA Office of Inspector General, Catherine Gromek, said the primary purpose of the visit “was to inspect the emergency department, radiology and the outpatient pharmacy window and to interview staff who had knowledge of the events.”

“At the time, we did not have the contact information of the family friend,” she wrote in an email, referring to Redwine. “While onsite, the Facility Director gave us the contact information and the team leader called the family friend and left a voice message. We did not hear back from the family friend until after the team was en route back to their office which is outside Nevada.”

Redwine disputes the inspection team’s effort to reach her.

“During this period I had my phone with me,” she said. “I always return calls within 12 to 24 hours.”

Gromek said it is “not an unusual practice” to conduct interviews by phone. She said five team members were on the conference call with Redwine on Dec. 23.

Regarding a question about the inspectors not making a recommendation to keep video recordings longer than 30 days, Gromek said the team’s recommendations “focused on improving the delivery of care.”

Said Redwine: “It just brings tears to my eyes that nothing has changed.”

She said she has little faith for reform in the VA based on her experience with the VA inspector general staff coupled with a news release last week from the House Veterans Affairs Committee citing a watchdog report in the Washington Examiner that the VA inspector general knew about wait time manipulation in Phoenix six years ago but kept its report secret.

“Past behavior usually predicts future behavior, and therefore it’s obvious that the abuse will continue and local authorities will just turn their heads,” she said. “It is obvious that power, position and money is much more of a priority than any veteran.”

Contact Keith Rogers at krogers@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0308. Find him on Twitter: @KeithRogers2.