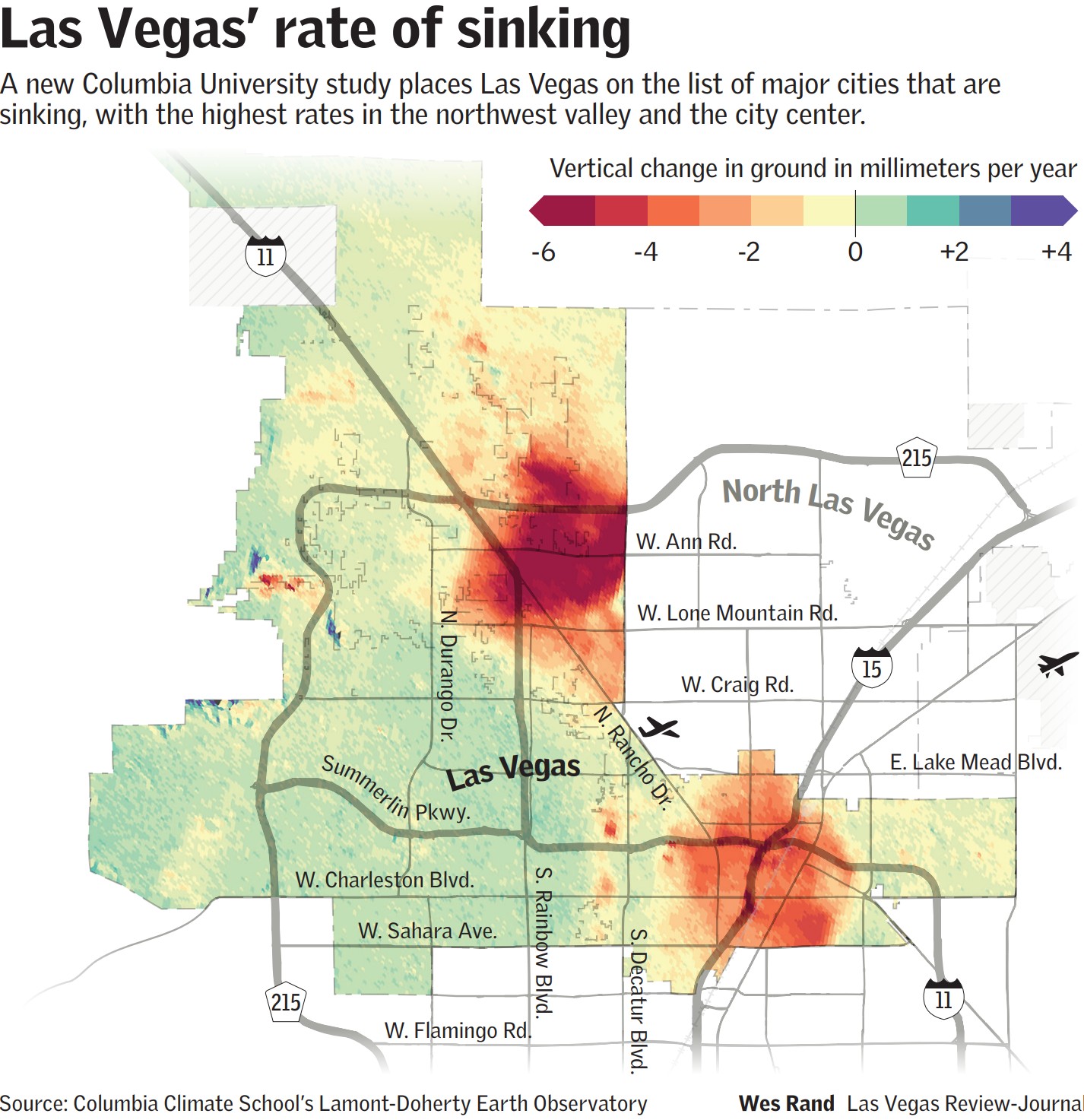

Is Las Vegas sinking?

A new study places Las Vegas on a list of 25 cities that are sinking farther into the ground every year. But it doesn’t rank as highly as it would have in the 1960s or ’70s.

In fact, the water beneath our feet, and the rapid use of it, once put Las Vegas into crisis mode.

During the 1960s, the city faced a different type of water crisis, years before Lake Mead became the city’s primary source of drinking water. Early residents pumped almost twice the amount of groundwater than was restored every year from Spring Mountains snowpack and rain, according to state reports.

For some, that had dire consequences. As groundwater levels declined, parts of Las Vegas as they knew it began to sink as much as 3 centimeters each year, including one formerly segregated North Las Vegas neighborhood in the shadow of the Strip where floors fell, ceilings cracked and backyards began to bend.

Using satellite and groundwater data, the Columbia University study released in early May has again put a spotlight on subsidence, ranking Las Vegas as one of the cities that continues to sink — primarily because of groundwater pumping.

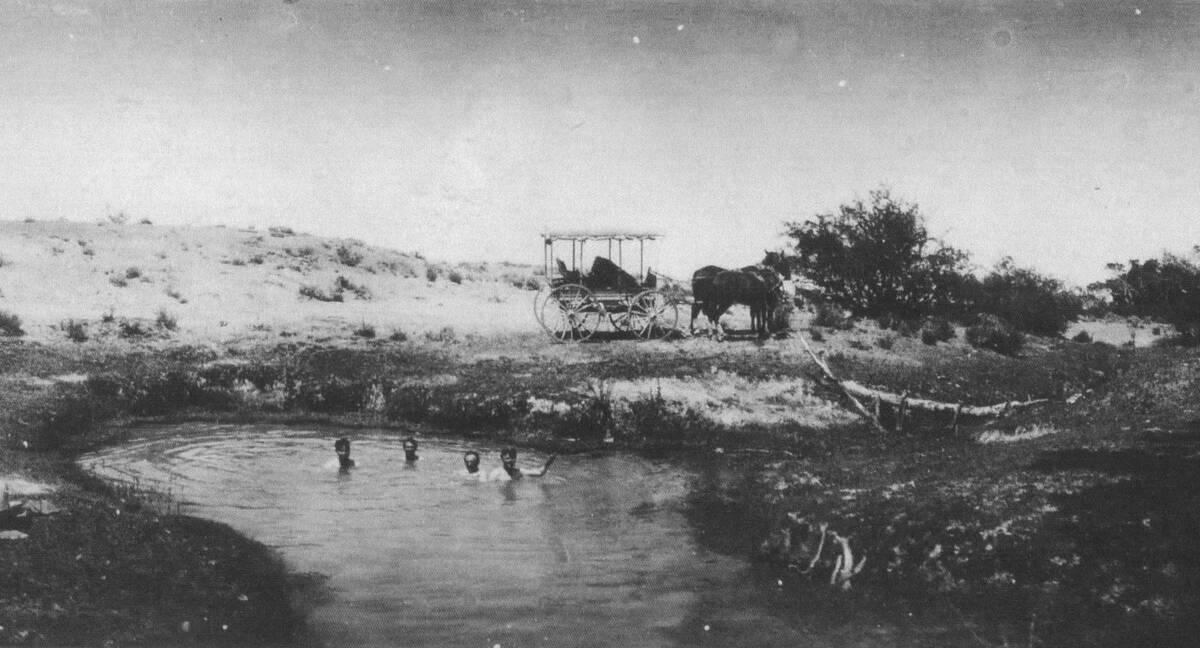

In early days, historical subsidence raised questions about whether Las Vegas, where freshwater springs and lush greenery had inspired explorers to name it “the meadows,” could ever be a sustainable place to live.

“In the late ’60s, the springs stopped flowing,” said James Prieur, a licensed geologist and the Southern Nevada Water Authority’s hydrology supervisor. “They had to put pumps in the wells, and as a result, the water levels in some places dropped over 100 feet. All these clays and silts that originally had high pressure underneath them were all of a sudden deflated.”

Leonard Ohenhen, the study’s lead author and a postdoctoral researcher at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, said the purpose of the research was to warn lawmakers and everyday Americans about subsidence.

“People are often not attuned to land subsidence because often you do not see the danger present as clearly or as visibly as other major hazards,” Ohenhen said. “The aim of this study was to make an invisible hazard, which is land subsidence, visible to communities, so that it becomes something that registers more in decision making.”

Houston emerged as the fastest-sinking city, with 40 percent of its area subsiding more than 5 millimeters every year. Other Texas metros weren’t far behind. Only two small portions of the Las Vegas area, in the northwest valley and the city center, are close to Houston’s measurement.

Lake Mead’s role

It was the mighty Colorado River that came to Sin City’s rescue, in more ways than one.

In 1987, the water authority began a process that would bank more than 100 billion gallons of river water in the ground to stop neighborhoods from sinking as much as possible.

And it worked: A 2008 study found that sinking rates in the highest-risk area of the northwest valley decreased from more than 3 centimeters a year to less than 1 centimeter. It’s not a complete fix, but a marked improvement.

John Bell was the lead author of early studies that kept tabs on subsidence until he retired from the Nevada Bureau of Mines about a decade ago. Bell didn’t contribute to the most recent study, but the problem areas were again identified and rates of sinking were on par with his prior findings, he said.

In an interview, Bell praised the so-called aquifer recharge program as Las Vegas’ saving grace when it comes to slowing its rate of sinking. The most affected areas of the northwest valley had sunk as much as 6 feet, according to his 2008 analysis.

“That was a very effective program,” Bell said. “It reduces the net groundwater reservoir withdrawal, and that has reduced much of the subsidence.”

That massive amount of water is banked in the ground, dually serving as a savings account for Las Vegas if freshwater is needed in a pinch, such as if a water main breaks or a power outage occurs.

“That’s what’s in place for a short-term emergency,” said Prieur, of the Southern Nevada Water Authority. “We wouldn’t be able to provide 100 percent of that water, but it would be able to at least help out.”

‘State of suspension’ for sinking neighborhood

For some longtime residents of the Windsor Park neighborhood in North Las Vegas, subsidence has dictated their quality of life for decades.

It was one of the first all-Black housing communities built up in the 1960s, when segregation and discriminatory policies from banks determined where Black Las Vegans could and couldn’t live.

In a 2021 UNLV documentary, law professor Frank Fritz said groundwater pumping exacerbated the natural geological faults below the neighborhood that residents say was once bustling and cheerful.

“When the groundwater is drawn out, the ground sinks. But near the faults, parts of the ground sink more,” Fritz said. “If your house is on top or near one of those cracks, your house cracks, pipes crack, roads crack.”

Nevada Sen. Dina Neal, D-North Las Vegas, was the legislator behind the Windsor Park Environmental Justice Act — an effort to ease residents’ decadeslong fight with the city to offer money for relocation. The 2023 law, signed by Republican Gov. Joe Lombardo, made $37 million available to purchase private land and offer residents new homes.

However, Neal has again proposed a bill that would amend the 2023 law, Senate Bill 393, which passed the Senate and may head to Lombardo if the Assembly pushes it through.

The purpose of the new bill is to allow funds to be used to pay out existing mortgages, ensure all residents of the neighborhood can benefit from relocation and allow the construction of a park memorializing the history of the neighborhood. Without it, Neal said, the only permitted action is building the houses on the new land.

“If this doesn’t move, it would leave the families, once again, in a state of suspension,” Neal said in a Wednesday interview.

A spokeswoman for Lombardo didn’t answer a question about whether he would sign the bill if it came across his desk, instead saying the governor would fairly evaluate it as he would any other proposal.

While it’s an extreme case, Windsor Park should be a warning for how subsidence caused by groundwater depletion can affect low-income and marginalized communities, Neal said.

“Subsidence is real, and it costs if you don’t take care of it at the time that it’s going on,” Neal said. “There’s a lot of education needed.”

Contact Alan Halaly at ahalaly@reviewjournal.com. Follow @AlanHalaly on X.