How Summerlin helped shape modern Las Vegas

It was a perfect match.

The booming Las Vegas Strip needed a place to house workers for new mega-resort jobs.

At the same time, a fledgling master plan on the west side needed homebuyers.

But that master plan — Summerlin, launched 25 years ago this month with the opening of Summerlin Parkway — would become much more than a bedroom community for the resort district.

Following the lead of a smaller Henderson master plan before it, Summerlin would take planned communities to a new level, shaping how all of Southern Nevada grew and how most Las Vegans live.

Don’t take it just from us.

Summerlin “has evolved into an extraordinarily large and mature community, and in the process has redefined for its region the concept of a master-planned community,” said researchers with the Urban Land Institute, a national nonprofit that promotes sustainable land use, in a 2002 case study.

As it evolved, Summerlin’s place in the national spotlight helped show people they could live normal, suburban lives away from the Strip — a vital image upgrade for a town with a somewhat shady past and a need to attract a fresh labor pool.

The community also became a yardstick for all Las Vegas builders, said Dennis Smith, president and CEO of Home Builders Research. Developers wanted their communities to be just like Summerlin or completely unlike it. Either way, Summerlin colored what they built.

With at least 20 years of development remaining, Summerlin is likely to keep shaping the region’s standard and style of living. Its 5,500 acres still in desert is bigger than any other local master plan — three times larger than the northwest’s 1,700-acre Skye Canyon, and more than double the 2,600-acre Park Highlands planned in North Las Vegas.

To understand Summerlin’s influence, start with its inception.

A HOWARD HUGHES HIDEAWAY

By size alone, Summerlin was destined to drive the market.

The community sits on 22,500 acres, or about 35 square miles, that tycoon Howard Hughes bought for $3 per acre in 1952 in the Las Vegas Valley’s western foothills. Hughes thought he might need to relocate his California aerospace and aircraft business from a coast vulnerable to a Cold War-era missile attack. It would be a generation before houses replaced hangars on the drawing boards.

Summa Corp. — The Howard Hughes Corp.’s name until 1994 — announced Summerlin in 1988. To make development manageable, the 80,000-home community would be broken into 31 villages. Linking the villages would be a system of biking and walking trails spanning more than 200 miles — equal the distance from Las Vegas to Tonopah.

It wasn’t the first time Southern Nevada had seen a big master plan. Henderson’s Green Valley debuted in 1978 with 7,100 acres, but at three times that size Summerlin was Green Valley on steroids. The specs boggled local minds: A 50-year buildout to accommodate 200,000 residents, which was about a third of the entire valley’s 1988 population of 650,000.

“When you first heard about it, the enormity of it was just beyond comprehension for almost anybody in Las Vegas,” said Smith, who moved to Las Vegas that year. “Nobody had seen anything like it.”

Back then, Rainbow Boulevard was the edge of town. When the four-mile Summerlin Parkway was cut into the desert west of U.S. Highway 95’s Rainbow Curve, some derided it as “the road to nowhere.”

“My first thought was, ‘Holy s—. They’re gonna build what, and how much, out there?’ It was just too much land, and too far out there,” recalled Bob Fielden, an architect and urban planner who moved to Southern Nevada in 1964. “It was crazy, whacko stuff.”

It wasn’t so crazy if you looked at what was happening on the Strip. The Mirage kicked off the modern mega-resort era in 1989. From 1990 to 1993, the MGM Grand, Excalibur, Luxor and Treasure Island opened. Clark County’s population nearly doubled in a decade, hitting 1.36 million in 2000.

The Howard Hughes Corp. had the land and saw the opportunity to try something new.

How different was their plan? In pretty much every way. If you’ve lived in Providence, Mountain’s Edge, Green Valley Ranch, Inspirada or any other local master plan in the past 20 years, you might take Summerlin’s early ideas for granted. But in 1990, they were bold, new and not always embraced.

A WHOLE NEW WORLD

Builders initially didn’t bite at the community’s development pads.

Developer Mark Fine, who was then overseeing the build-out of Green Valley, blamed a blend of concerns, not the least of which was Summerlin’s special improvement district fee.

A first in Southern Nevada, the fee wasn’t widely understood. Each new home in Summerlin would come with a 10-year assessment averaging $400 to $500 per year to cover city of Las Vegas bonds for construction of roads and other infrastructure. The idea was to finance the infrastructure with the bonds and shift development money to build parks, trails and cultural centers that would lure buyers.

Before Summerlin, the typical approach was to put up homes and wait for the city to add parks, often years later.

Nor did it help that Summerlin had dozens of design requirements, Fine said. No flat roofs, for example. Multiple peaks and elevations were required to echo mountains to the west.

Then there was the developer’s lack of experience, Fine said. The company had never built a large-scale residential community.

“Even though they (Summerlin) had the land and the money, there was not a high level of confidence with builders in what would be delivered,” Fine said. “I think they were looking at stacks of documents that were so convoluted, with restrictions on what builders could do and not do, and then you had the (special improvement district). Builders were interested. They needed land. But they couldn’t make that leap not knowing what would happen.”

Fielden recalled another early issue. Summerlin’s earliest plans called for much smaller community parcels, so that multiple builders would put up more diverse housing.

“They were smaller neighborhoods, rather than subdivisions,” Fielden said.

Builders didn’t think the approach or the cost structure made sense, Fielden said.

Ultimately, the master plan shifted to larger subdivisions, following a Southern California model, Fielden said.

By 1990, the year before the first family moved in, Summerlin had something to show for its infrastructure-financing method. The seven-acre Hills Park on Hillpointe Road opened with a picnic pavilion, outdoor amphitheater and stage, tennis and volleyball courts and a kids’ play area.

And Summerlin fixed the inexperience issue in 1991 by poaching Fine from Green Valley, where he had developed a reputation for master-plan expertise.

The strategy paid off: In 1992, just one year after builders began delivering homes, Summerlin claimed the first in a decade-long string of No. 1 rankings for new home sales nationwide.

The special improvement district fees remain an issue to this day, however, and some competing developers capitalize on it. American West Development advertises its fee-free lifestyle at its Highlands Ranch master plan just north of Southern Highlands.

But many more communities embraced the districts.

“Summerlin made them acceptable, and then everyone did it,” Fine said.

If you’ve visited Mountain’s Edge’s Exploration Peak Park with its restored mountain, or Aliante’s Nature Discovery Park and “dino dig” sandbox — both finished well before most residents moved in — you’ve seen Summerlin’s development doctrine writ large across the valley.

And that isn’t all.

To take amenities up a notch, Summerlin executives reshaped the homeowners association as a sponsor of community events. It might have been the nation’s first instance of a master plan’s HOA focused as much on quality-of-life programs for residents as preserving integrity of housing stock, said Dan Van Epp, who followed Mark Fine as Summerlin’s president from 1995 to 2004.

It took some legal wrangling, Van Epp said, but in 1995 the fix was complete. Easter egg hunts, 4th of July parades, “snow” days and art-in-the-park festivals followed.

“I think that actually spread across the country from us. It was something that was very much new with Summerlin,” Van Epp said.

Builder cooperative fees helped fund the events — something Fine said Green Valley pioneered but Summerlin “took to the next level.”

So next time you attend a pet parade in Anthem or rent from Cadence’s bike-share program, you know who to thank.

SELLING QUALITY OF LIFE

Through its look and shape, Summerlin also pioneered smaller intangibles you probably see in your neighborhood today.

Earth-tone stucco walls instead of whitewashed concrete block? Summerlin.

Landscaped medians with walls and monuments set back from streets? Summerlin.

Stores around the edge of a shopping district with unsightly parking concealed in the center? Summerlin’s Trails Village Center, which opened in 1998.

Limits on sign heights for fast-food restaurants and gasoline stations? You know who.

The developers also sold prime real estate — think the corner of Town Center and Alta drives — below-cost to churches as a way to boost community institutions from the start.

But Summerlin went really big on several key ideas that affect legions of Las Vegans, even if they don’t live in a master plan.

Consider the boundaries of Red Rock Canyon National Conservation Area, created by Congress in 1990.

Summerlin’s initial 25,000 acres ranged all the way to what is now the conservation area’s visitor center. The Nature Conservancy initiated and brokered a 1988 deal that swapped the community’s westernmost portion for federally owned parcels to the south. Another west-for-south land swap was completed 12 years later.

The trades left Summerlin 10 percent smaller, at 22,500 acres, to help preserve an outdoor treasure.

“We like to protect the view shed as much as we can, and we don’t like to slice and dice mountains,” said Tom Warden, The Howard Hughes Corp.’s vice president of community and government relations.

Summerlin also led in water conservation as an early adopter of desert-tolerant landscaping at a time when nearby developments, including The Lakes and Desert Shores, were putting in artificial lakes, creeks, waterfalls and grassy common areas.

“Summerlin was really bucking a trend. Up to that point, everyone needed a lush landscape to sell property,” said Dick Glanville, a California-based landscape architect who worked on some of the earliest villages. “Summerlin spent a lot of time and effort to make (desertscape) a positive thing.”

Mark Paris, The Howard Hughes Corp.’s vice president of marketing from 1986 to 1992, pressed for desert landscaping.

“Given the enormity of (Summerlin), we wanted to make sure we didn’t do things on the front end that we couldn’t live up to, and that wouldn’t be responsible to the property and to the legacy of Howard Hughes,” said Paris, now president and CEO of The LandWell Co., which is developing the palm tree-free Cadence master plan in Henderson. “We were concerned about water conservation and making sure the community was compatible with the surrounding environment. We were very concerned about it at the beginning because we were surrounded by lush communities, but we felt people in the community would get to the point where they recognized the benefit of it.”

The earliest example of desert-friendly design is at the 22-year-old Pueblo Park near Lake Mead Boulevard and Buffalo Drive. Early talk of grading the park’s natural wash and carpeting the area with turf was dismissed quickly because of development and water costs, Glanville said. Instead, a path follows the wash, and native vegetation stayed.

Some of Summerlin’s landscaping practices shaped conservation guidelines adopted by local water agencies. One example: The 18-inch ribbon of gravel between grass and curb that reduces runoff into streets.

“The water districts adapted stuff we did and hit it hard because they didn’t think they would have pushback from developers, because Summerlin was such a success,” Glanville said.

Finally, The Howard Hughes Corp. struck a big blow against traffic tie-ups on the burgeoning west side in 2001 by giving Clark County 520 acres to accelerate development of the 215 Beltway. The gift included eight miles of right-of-way for a regional trail system that eventually will circle the valley. The company also spent $58 million to put the beltway in a trench aimed at reducing noise pollution.

Clark County officials say the land donation sped up construction of the beltway’s western section by 10 years.

“It’s a perfect example of what you can do when you control this much land under one ownership,” said Kevin Orrock, Summerlin’s current president. “If our 22,500 acres were held by different parties, how difficult would it have been to get the beltway done in such a short time period?”

Van Epp called the beltway donation a “huge burden” but one that makes him proud.

“If that had not been done, the city would still be developed, but with immense traffic congestion,” he said.

OPPORTUNITIES MISSED

Even without Summerlin, Las Vegas was destined to grow west.

“Growth still would have come, but it would have been done in more piecemeal fashion, and it wouldn’t have had the aesthetic value and functionality Summerlin has,” said Pat Shalmy, who was Clark County manager when Summerlin got underway. “It would have been developed in smaller pieces, as the rest of the valley has been developed. While some of that other development is very good, I just think it turned out better than any of us imagined under the one-master-plan approach.”

Beyond “raising the bar on infrastructure,” Summerlin helped reshape local thinking on incorporating multifamily homes into upscale single-family suburbs, Fielden said.

Where it missed the boat, though, was in those larger subdivisions.

“What ended up there ultimately is pretty much what you can find all across Orange County,” Fielden said. “They brought in some stone to put on their stucco boxes, but they’re still principally stucco boxes.”

Summerlin also missed an opportunity to think big on public transportation, he added.

“Probably two-thirds of the miles of vehicle trips in and out of Summerlin are the maids and landscapers and others who work for the people who live in those neighborhoods,” he said. “I think it’s tragic that we never think about what it takes to support the places where we live, and how we get workforces there other than having them come in cars and trucks.”

But Smith said there’s just one element of Summerlin he would change — a relative lack of affordable housing.

The first Summerlin homes, in Woodside Homes’ Panorama Pointe near Lake Mead and Del Webb Boulevard, sold for an average of $129,000 at a time when the median new home price was $113,950, Smith said. But Summerlin’s new-home median in 2014 was $475,000, compared with a marketwide median of $291,662.

And those Panorama Pointe homes? Today, some of them go for more than $300,000, compared with a marketwide single-family resale median of about $205,000.

Summerlin does have resale condos listed for as little as $84,000 in its northern end, but as the master plan finishes its final few thousand acres, prices will test the market — and projects likely will set new trends.

AN EXPENSIVE END-GAME

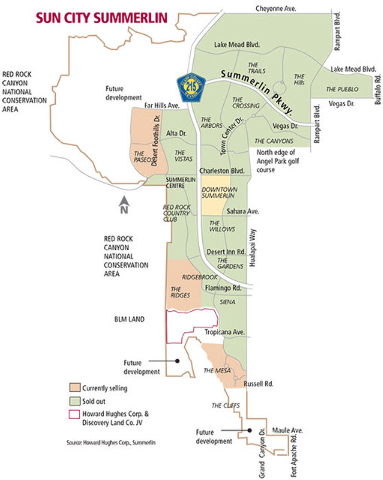

Summerlin’s remaining 5,500 acres is concentrated in the southern foothills around Hualapai Way and Patrick Lane; the foothills to the west of The Mesa, The Paseos and The Arbors villages; and Downtown Summerlin.

Hills mean higher development costs that must be built into home prices. And because parcels might be uneven, with lots at grades of 5 percent to 7 percent, densities in some communities will drop. Lower densities could require higher home prices as well, because development costs are distributed among fewer homes. Consider The Howard Hughes Corp.’s joint venture with Discovery Land Co. to develop 250 homes on 555 acres near Tropicana Avenue and Town Center Drive, with hilly lots of up to three acres and parcel prices starting in the low seven figures.

“You have a tremendous challenge when you have any parcel with a grade change of 5 percent from one end to the other,” said Julie Cleaver, vice president of planning and design at The Howard Hughes Corp. “How do you transition a home on that grade? We’ve worked through some of those challenges at The Paseos, but we’re still getting better at what those transitions can look like. We may sacrifice density, but we may also be working with different kinds of products to give us the density we need.”

In Downtown Summerlin, The Howard Hughes Corp. will go the opposite direction. Its 1.6 million-square-foot shopping center, the 200,000-square-foot One Summerlin office building and Red Rock Resort are in place. Set to follow are as many as 4,000 townhomes, apartments and mid- and high-rise condo towers for up to 10,000 residents. That’s a population density more like Manhattan than anything in Southern Nevada.

Downtown Summerlin would make the master plan Southern Nevada’s first true “edge city,” a dense cluster of upscale offices, shopping centers and entertainment districts outside central business districts on the Strip and downtown.

“I think of it like Tyson’s Corner, Va.,” Van Epp said. “That area went through two or three decades of fairly low-density construction, but out of necessity, as it built up around highway interchanges, it got redeveloped to a higher density, with more height involved.”

Even with all of those development plans, observers disagree on how important Summerlin, which has more than 100,000 residents now, will remain as it nears build-out.

“It’s going to be less influential than it has been as we rethink living in this valley,” Fielden said.

He pointed to principles forged by Southern Nevada Strong, a federally funded regional coalition looking at long-term development. It envisions more varied housing stock that includes affordable apartments and homes on big lots; expanded public transportation such as light rail; and streets safer for walking and biking.

“Places like Summerlin are going to be almost examples of the past rather than the future,” Fielden said.

But Smith said Summerlin always will be perceived as an “upgrade or move-up product,” ever “a barometer for measuring any new master plan.”

Cleaver said she wouldn’t have it any other way.

“Any time we do anything, because of our size, it can’t help but have an impact on the rest of the valley,” she said. “We think in a big way. It’s really important to us to raise the bar on the standard of living not just for Summerlin, but for people across Las Vegas.”

Contact Jennifer Robison at jrobison@reviewjournal.com. Follow @J_Robison1 on Twitter.