Lack of children’s mental health services impacts hospital ERs

The number of mentally ill adults going to Southern Nevada emergency rooms has significantly decreased, but the number of children in the same situation is growing, state lawmakers were told this week by experts in the field.

Various issues are driving the growing number of mentally ill children in emergency rooms, including the continued lack of resources for them, health insurance limitations and the needs of autistic children.

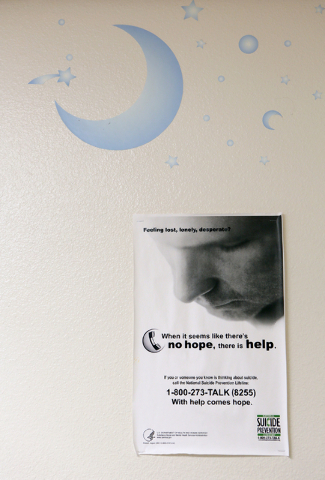

Suicide and attempted suicide among youth also highlight the need for better mental health services for children. Earlier this month, a 14-year-old girl’s body was found at Coronado High School by authorities who said she took her own life.

Dr. Jay Fisher, head of University Medical Center’s pediatric emergency department, said he will work with the Clark County coroner’s office to review death certificates of recent suicides in the county and run them through the hospital’s database. He wants to know if any of them had sought or received mental health services or if they never attempted to get help before taking their own lives.

At a recent meeting, a group that’s been tackling children’s mental health issues voiced its growing concern about children’s mental health.

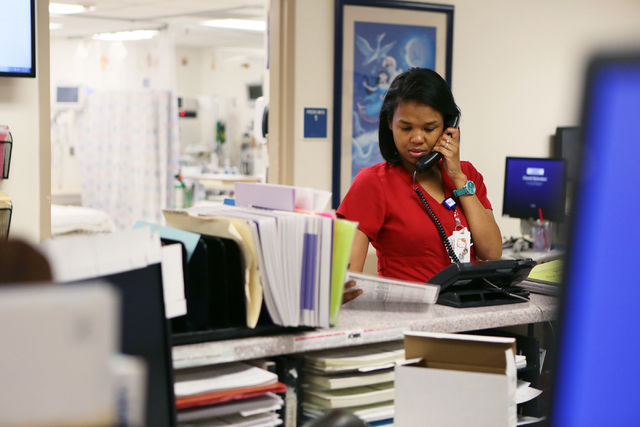

“This is the polio of our era,” Fisher said during the quarterly Pediatric Mental Health Task Force meeting at Sunrise Hospital and Medical Center in late April.

State lawmakers, communities and providers need to make children’s mental health a priority, those advocating for the issue said. But parents also play an important role — they know their children best and should be on the lookout for red flags.

The Clark County Children’s Mental Health Consortium recently released the 2015 status report on children’s mental health. The report calls for various measures, including providing more mobile crisis intervention for youth.

“Without easy access to crisis intervention and stabilization services, families in Clark County have been forced to utilize local emergency rooms in order to obtain behavioral health care for their children,” the report reads.

The report cites a UNLV study that found Nevada lags significantly behind neighboring states in providing adequate funding for children’s mental health services.

Desert Willow Treatment Center, with 58 beds, is the only public hospital that offers residential treatment and acute care to children with mental health issues. Eight of those beds are closed because of staffing issues, said Kelly Wooldridge, deputy administrator for the state’s Division of Child and Family Services.

State lawmakers “need to pay more attention to the fact that there are mental health needs and they need to be addressed,” said Rosemary Virtuoso the Clark County School District’s director of student threat evaluation and crisis response.

Lack of services is just one facet of the problem. The limitations families face with health insurance is another.

Often, a child needs intensive services or a different type of service, but parents are limited to what their insurance will cover, Virtuoso said. As a result, the child is not stabilized.

“The Legislature needs to look at and address how insurances provide support for mental health needs of children so the needs of the kids are being met,” Virtuoso said.

The emergency department at Sunrise Children’s Hospital recently began to see a wave of parents showing up indicating they were referred there by a psychiatric hospital with no beds available, said a registered nurse from Sunrise during the quarterly meeting.

“We’ve seen a huge increase in that,” said the woman, who declined to give her name to the Review-Journal. “They are using us as a holding area.”

The volume of patients coming into the emergency room is up by about 23 percent, and the number of beds is still the same — 15, said Ryan Pace, director of the pediatric emergency department at Sunrise.

The pediatric emergency department sees hundreds of children with behavioral health issues, said Brendan Bussmann, Sunrise’s vice president for strategic development and marketing. It holds an average of two to three young patients a day awaiting placement.

Emergency departments at Valley Health System hospitals are having the same problems, spokeswoman Gretchen Papez said.

At UMC, the pediatric emergency department sees an average of three to four mentally ill children a day. Their emergency room wait time averages 10 to 12 hours, Fisher said.

But the department is now also seeing autistic children with behavioral issues.

“Behavioral facilities are hesitant to take those kids,” he said.

Officials at Montevista Hospital, a private psychiatric hospital in Las Vegas, agree the need is on the rise, said Jim Shaheen, president of Strategic Behavioral Health, owner of Montevista Hospital and Red Rock Behavioral Health Hospital in Las Vegas.

There’s been a shortage of beds for acute psychiatric inpatient care for children for some time, he said. The hospital has 38 beds for such cases and recently opened 48 residential beds.

Montevista only refers patients to an emergency room if there’s a medical condition that needs to be cleared first.

And just like the group of doctors, mental health professionals, hospital administrators, school officials and a judge, Shaheen agrees emergency departments are not the solution.

“The ERs are supposed to be used for emergency uses,” he said. “We strive to educate the community that they don’t need to go to the ER unless there’s a medical issue.”

Contact Yesenia Amaro at yamaro@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0440. Follow @YeseniaAmaro on Twitter.