Las Vegas medical company offers tool to fight Ebola

The chief medical officer of a Las Vegas company could be meeting within days with the head of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention about a monitoring device that could be a pivotal tool in the fight against the deadly Ebola virus.

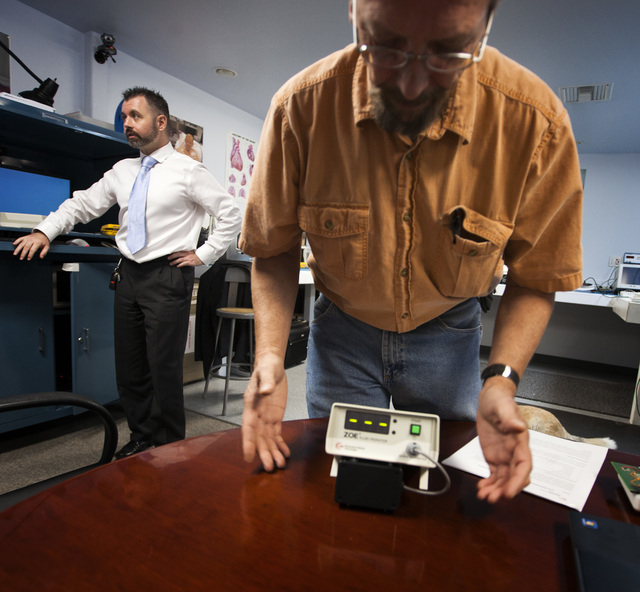

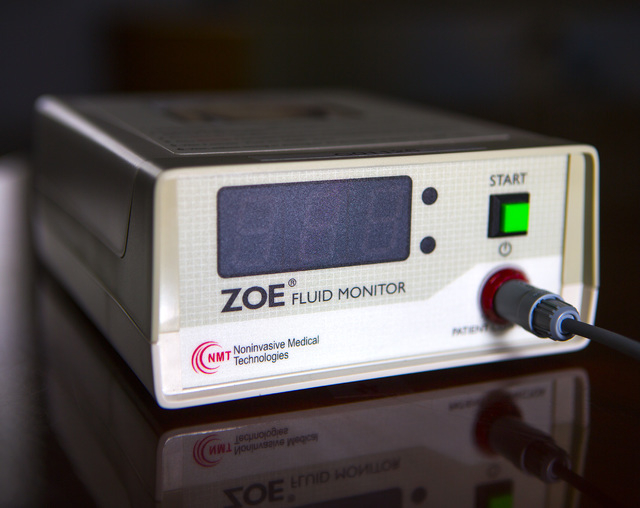

Noninvasive Medical Technologies, or NMT, manufactures the ZOE fluid status monitor, which applies electrical current to the body to determine changes in hydration. Marc O Griofa, chief medical and technology officer for NMT, said the ZOE monitors can help health care workers identify Ebola patients more quickly and reduce the risk of the virus spreading.

O Griofa was awaiting word Monday on when the meeting with CDC Director Dr. Thomas Frieden would take place during which the ZOE monitor would be demonstrated.

The devices were developed to help in the treatment of patients with fluid management problems, and they were used several years ago to monitor dengue fever patients in Malaysia, O Griofa said. The units retail for $1,500 each, he said.

The dengue and Ebola viruses both cause hemorrhagic fever, which results in fluid moving out of cells in the body. The ZOE monitor can detect those changes in hydration and will be able to identify an Ebola patient before people start showing symptoms such as fever, headache, weakness, diarrhea or vomiting, O Griofa said.

To acquire the Ebola virus, a person must have contact with the blood or body fluids of a person sick with Ebola or come in contact with objects that have been contaminated with those fluids. Symptoms can present from two to 21 days after exposure, but the average is eight to 10 days, according to the CDC.

To test for Ebola, a patient must be presenting Ebola symptoms because the virus exists in too small an amount to be detected beforehand. The fluid shifts, however, can point to Ebola even before symptoms appear, and by detecting those changes in hydration, the ZOE can identify potential patients with less risk to health care workers, O Griofa said.

Potential patients could be isolated earlier by using the ZOE monitors, and the risk for spreading the disease also would decrease significantly, O Griofa said.

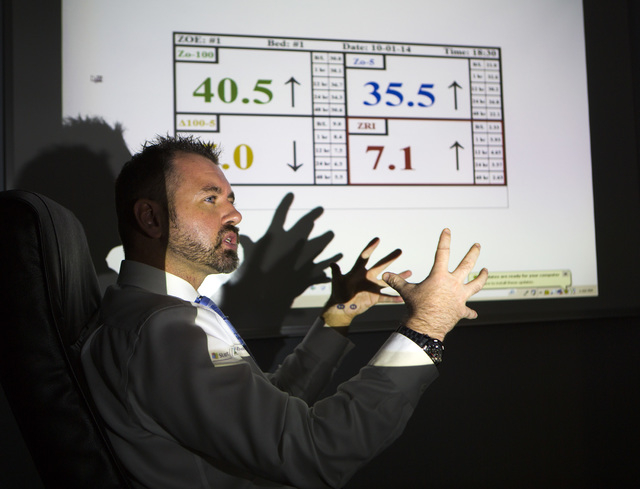

“If those numbers start to change, we have a high degree of confidence that the person is going to get sick, ” he said. “If the numbers change further, we have a high degree of confidence that the sickness is going to result in morbidity.”

The monitors provide a much more thorough level of assessment than simply taking someone’s temperature to look for a fever, O Griofa said.

“Several factors are key to identifying Ebola, and temperature is not it,” he said.

The monitors relay data to a cloud server, and the information can be tracked remotely by health professionals providing real-time assessments of several patients, O Griofa said.

“You can’t have a health care workers at every given bed, but these devices will allow you to monitor, triage and analyze multiple patients at any given time,” he said.

The death toll from the Ebola outbreak in West Africa on Monday stood at 4,033, and the number of suspected, probable or confirmed cases is more than 8,400, according to the CDC. The fatality rate in the current outbreak is about 50 percent, according to the World Health Organization.

NMT representatives have been in contact with CDC officials under the auspices of supplying ZOE monitors under an urgency exception in government contracting. Staff from Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, D-Nev., also have been involved in expediting the process, O Griofa said.

Phil Hamski, ZOE inventor and director of product development for NMT, said several hundred of the monitors could be supplied initially to health care workers in Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea, the countries most affected in the current outbreak. The company is ramping up production to be able to supply 10,000 of the devices over the next couple of months, Hamski said.

ZOE fluid status monitors can provide biometrics about hydration similar to how an electrocardiogram monitors heart activity, Hamski said.

“It’s measuring a mechanical signature instead of an electrical signature,” he said.

Hamski referred to the ZOE as a “stick-on Swan-Ganz,” a catheter inserted through a vein into the right side of the heart to monitor heart function and blood flow. A Swan-Ganz is performed in a cardiac catheterization lab, but a ZOE can be performed with less difficulty than using a defibrillator for cardiac resuscitation.

The device, which requires a doctor’s prescription for use in the United States, is designed to be simple enough to be used by an 88-year-old blind patient wearing mittens, Hamski said.

The devices most commonly have been used in hospitals or home health care settings for patients living with heart failure, end-stage kidney disease, coronary artery disease or recurrent dehydration. ZOEs have electrodes that attach to the top of the chest and the bottom of the sternum. The data can indicate whether patients are complying with their recovery.

The ZOE also provides averages of the hydration status for the previous hourlong, 12-hour, 24-hour and 48-hour intervals to give medical practitioners an objective assessment of how a patient is progressing or digressing, O Griofa said.

ZOEs could be employed in several ways in the current Ebola outbreak. In addition to helping identify Ebola patients, ZOEs could increase survival rates by indicating the need for fluid replacement during treatment, O Griofa said. Because no cure for Ebola exists, the treatment options essentially are reduced to supportive management, allowing the body’s own immune system time to muster a defense to the virus.

The monitors would continue to give medical professionals vital information on the status of their patients throughout the course of their treatment, he said.

Contact Steven Moore at smoore@reviewjournal.com or 702-380-4563.